Posted: October 1st, 2018 | Author: Nicholas Minns & Caterina Albano | Filed under: Film | Tags: David Morris, Erik Bruhn, Jacqui Morris, Margot Fonteyn, Patricia Foy, Rudolph Nureyev, Russell Maliphant | Comments Off on Jacqui and David Morris: Nureyev, at the Curzon Mayfair

Jacqui and David Morris, Nureyev, Curzon Mayfair, September 25

Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn in Marguerite and Armand (photo: Frederika Davis)

Since Rudolf Nureyev defected to the West in 1961 there have been so many interviews, news items, reports, articles, performance videos, films and documentaries about him that a new documentary seems almost redundant. What sibling directors Jacqui and David Morris have evidently set out to achieve with their new biopic Nureyev is to expand the dancer’s life for the big screen by not only adding a theatrical treatment of his childhood but by placing his 32 years in the West within the context of the culture and politics of the Cold War. Dance lovers may already be familiar with much of the material — though there are hitherto unseen clips of his performances with Murray Louis, Paul Taylor and Martha Graham companies — but Nureyev is clearly conceived for a wider audience with, for some odd reason, a 12+ certification.

Just two months after Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin returned from space in 1961, placing the USSR’s technological achievements in full view of the world, Nureyev dealt a public relations bombshell to his native country by making a dash for freedom at Le Bourget Airport. Gagarin, the young hero and poster boy of the Soviet space program and Nureyev, the young soloist of the Kirov Ballet who had just created a sensation in the company’s Paris performances, may seem worlds apart* but in terms of soviet propaganda they were equally strategic and valuable icons. Nureyev’s defection was a devastating blow to the Soviet image and reprisals were taken against his family and fellow dancers. For Nureyev it was a huge risk whose personal price must have lain heavily on his conscience but he spent the rest of his life living and working voraciously — as the documentary demonstrates — to justify his belief in personal and artistic freedom; he beat the path subsequent classically-trained dancers have followed to experiment with contemporary dance forms. But even if he had left Russia, Russia never left him. The scenes of his return to his home city to visit his ailing mother and former teacher in 1989 for the first time since his defection are intensely moving not only as an insight into the heart of the man but as a reminder of how much he had maintained the values of Russian culture throughout his single-minded pursuit of a dancer’s life in the West.

Because the artist in Nureyev is indistinguishable from his person, the documentary invites us to discover both in what appears as a continuous performance, from footage of his dancing to interviews with Michael Parkinson and Dick Cavett to his detention in a New York police station to an intimate dinner party towards the end of his life in his Paris apartment; he is allowed to define himself in images and words, though rarely his own. There are a couple of clips from Patricia Foy’s 1991 documentary where he talks about his childhood but most of the comments come from his contemporaries, peers and critics as in the delightful appreciations by Antoinette Sibley, Yehudi Menuhin, Nigel Gosling and Clement Crisp.

Where Nureyev cannot represent himself is in his early years, for which the directors have substituted choreographic tableaux devised by Russell Maliphant. The invocation of Nureyev’s family in this way, like a film within a film, initially makes sense but as the tableaux try to cover his years in the Kirov school and company they no longer match the extraordinary self-will and charisma of their inspiration, a divergence that the superimposition of Nureyev’s early Kirov performances does little to mitigate. In an attempt to pull together the threads of the story, such cinematic devices, along with written quotations from various sources, generate a dense, rather fussy aesthetic that clutters rather than clarifies the rich canvas of archival material.

It seems in his single-minded desire to make up for lost time — he had only started training at the Kirov Ballet school at the age of 17 — Nureyev was drawn to older and more experienced dancers on whom to model himself and with whom to share his public and private life. One was Erik Bruhn whom he met soon after his defection and their mutual respect is captured in the wonderful footage of them working together at the barre in Vera Volkova’s studio in Copenhagen. The other legendary partnership on and off stage was with Margot Fonteyn and here again their relationship is allowed to speak poignantly through footage of their performances — the balcony scene and the tomb scene in Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet.

For the last decade of his life Nureyev was director of the Paris Opera Ballet, building a legacy that endures in the Nureyev Foundation, who supported the making of this documentary; in suggesting there hasn’t been anybody to replace him in the ballet world, Nureyev is a convincing tribute.

*One of the many items flung onstage during Nureyev’s first season in Paris was a headshot of Gagarin with a message at the bottom reading, Soar, Rudi, Soar!

Posted: March 19th, 2018 | Author: Nicholas Minns & Caterina Albano | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Andy Cowton, Critical Mass, Dana Fouras, Daniel Proietto, Dickson Mbi, Duet, Grace Jabbari, Hugo Glendinning, Michael Hulls, Other, Russell Maliphant, Still, Tim Etchells, Two Times Two | Comments Off on Russell Maliphant Company, maliphantworks2 at Coronet Print Room

Russell Maliphant Company, maliphantworks2, Coronet Print Room, March 13

Russell Maliphant and Dana Fouras in Duet (photo: Tom Bowles)

Russell Maliphant’s week at the Coronet Print Room in Notting Hill is a very intimate affair, to which the chic délabré intimacy of the former Coronet theatre is ideally suited. It is one of those theatres whose atmosphere critic Cyril Beaumont described as having a ‘warmth and friendliness that gives the spectator the feeling of being a member of a pleasant club’ and there is a sense of the membership of this particular club coming to pay homage to one of their own. It is not exactly a full evening — the first intermission is longer than the first two works — and it’s a performance of re-immersion into a body of work that has a very recognizable form of craftsmanship in which the influence of sculpture is evident in the plasticity of the dance movement. There is no indication in the program when these works were created, but it doesn’t really matter; however new Maliphant’s works may be there is always an element of the retrospective in their presentation. His synonymous association with the lighting designer Michael Hulls serves to reinforce this familiarity; it is a given that all four stage works are choreographed and directed by Maliphant and all lighting designs are by Hulls.

Maliphant creates material forms with the body that Hulls transforms in light. Their opus is at its best an exquisite aesthetic experience — as those who saw their collaboration on Afterlight with Daniel Proietto as Nijinsky might attest — but too often lacks the inspiration to rise above precious familiarity. Of the four works on the program this evening, the visual and emotional gauge is more aligned with familiarity than with the exquisite. In the duet with Dana Fouras and Grace Jabbari, Two Times Two, the sculptural forms are reminiscent of Maliphant’s Rodin Project: classical marble figures moving in a kinetic dream. Andy Cowton’s score and Hulls’ lighting subject the forms to a process of dematerialization until the final slicing arm gestures diminish to beautiful swathes of light. Critical Mass performed by Maliphant and Mbi is a meditation on balance and posture as they are redefined by tension and suspension. There is dexterity of movement as the centres of the dancers’ and that of the composition shift and hold still, building a critical mass through repetition. Hulls’ lighting here is subtle, but in Dickson Mbi’s solo section of his duet with Jabbari, Still, he is trapped in Jan Urbanowski’s animation that with Hulls’ lighting covers him in a moving barcode on a gloomy ground. When Mbi dances it is worth watching; to superimpose a light project that all but obscures his movement and reduces it to a mere plastic aesthetic is to take advantage of the choreography, and to do it in a way that is unsettling on the eyes is tiresomely self-indulgent.

The final work, Duet, is a world premiere in which Maliphant dances with his wife and collaborator, Fouras; it is the first time in fifteen years that London audiences have the opportunity to see them dance together and it is a moment worth celebrating. There is a genuine sentimentality here that is in the vein of a recording of Caruso singing Una Furtiva Lagrima that emerges from Fouras’s sound score. Interestingly, Hulls keeps a respectful distance in lighting Duet which allows a very personal narrative of two lovers to emanate from the choreography. It is a polished performance of natural elegance and carries an emotional implication that is not lost on the audience.

What to make of the fifth work on the program, Other? It is a ten-minute video installation that is played on a loop in the theatre’s smaller studio that shows Maliphant and Fouras, on their respective sides of a split screen, embroiled in the turbulent surf off the Atlantic coast of West Cork, gesturing wildly and powerlessly in their evening dress against its incoming force. It is not clear if the installation was made specifically for this week’s program or was edited from original material to bolster the length of the evening. It is ‘made from footage originally conceived, directed and shot by Tim Etchells and Hugo Glendinning’, with a sound score by Fouras. Other could well illustrate the condition of the artist flailing against the forces of contemporary society in which impotence becomes the subject of a work of art, except that without a context the very artfulness of its solipsistic concept turns the work in on itself and robs it of any wider significance.

Posted: October 6th, 2016 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Arthur Pita, Jackie Shemesh, James O'Hara, Jason Kittelberger, Luis F. Carvalho, Michael Hulls, Natalia Osipova, Qutb, Run Mary Run, Russell Maliphant, Sadler's Wells, Sergei Polunin, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Silent Echo | Comments Off on Natalia Osipova, Three Commissions

Natalia Osipova, Three commissions, Sadler’s Wells, October 1

Natalia Osipova and Sergei Polunin in Arthur Pita’s Run Mary Run (photo: Tristram Kenton)

Natalia Osipova is a dancer I could happily watch in any performance. Brought up in the Russian classical tradition, a supreme technician and dramatic presence, she is at home in the classical repertoire but itching to broaden her scope as an artist. Without retracting that opening statement, this evening of contemporary work for Osipova at Sadler’s Wells falls somewhere short of my anticipation. The issue is who commissioned this triple bill — first seen here in June — and why. Sadler’s Wells’ chief executive and artistic director, Alistair Spalding, suggests in the program’s welcome note that Sadler’s Wells commissioned the works, which happen to include two by Sadler’s Wells associate artists: Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Russell Maliphant. In Sarah Crompton’s overview of the evening in the same program she makes it appear that Osipova commissioned the works. But if she did, why so early in her drive to broaden her horizons would she commission new works from choreographers she has already worked with (Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Arthur Pita) so recently? And is Russell Maliphant’s choreographic process likely to expand Osipova’s artistic range? I don’t think so. No, it is unlikely Osipova commissioned these works but has instead lent her name and talent — along with those of her partner Sergei Polunin — to the evening in return for the creation of three works brokered for her by Sadler’s Wells. It’s a compromise in which neither party comes off particularly well artistically; Osipova is not challenged enough because the works fall short of providing her with a vehicle for her scope. Cherkaoui’s Qutb thinks about it in philosophical terms but delivers a trio in which Osipova’s desire for flight is constantly grounded and smothered by the overpowering physique of Jason Kittelberger and in which the only (rather uninteresting) solo is given to James O’Hara. Qutb is Arabic for ‘axis’ but the axis of the work is Kittelberger not Osipova. Some commission.

Maliphant’s Silent Echo without the lighting would be like watching Osipova and Polunin consummately messing around in the studio. Maliphant’s choreography is so totally dependent on the lighting of Michael Hulls (a dependence that has become derivative) that any artistic development for the dancers is merely subordinate to the Maliphant/Hulls formula; the greatest hurdle for them is to dance on the edges of darkness.

Pita’s Run Mary Run is the only work in which Osipova and Polunin have roles to explore; Pita puts them centre stage in a musical narrative of love, sex, drugs and death to the songs of the 60’s girl group, The Shangri-Las. Known for their ‘splatter platters’ with lyrics about failed teenage relationships, Pita invests Run Mary Run with a theme of love from beyond the grave that he can’t resist associating — in the opening scene of two arms intertwining as they emerge from a grave — with Giselle. But Osipova’s persona is closer to Amy Winehouse (whose album Back to Black was inspired by The Shangri-Las and whose life Pita cites as the major influence for the work), and Polunin in his jeans, white tee shirt, black leather jacket and dark glasses is more like bad-boy Marlon Brando than a remorseful duke. While Pita’s narrative mirrors the destructive relationships in Winehouse’s life, the romantic elements of raunchy duets, flirtatious advances and feral solos feed off the partnership of the two dancers. Pita is pulling out of them elements of their own lives and putting the audience in the privileged position of voyeurs; we are living their emotions in the moment. This gives the work its edge and inevitable attraction. The colourful lightness of Run Mary Run — thanks to costumes and sets by Luis F. Carvalho and lighting by Jackie Shemesh — thus reveals a genuine heart that saves the work from its dark parody. But such is the nature of the heart that Run Mary Run may only succeed with these two protagonists.

Pita’s work is a step in the right direction for Osipova, as is the idea of her performing works outside her comfort zone. But if she really wants to find works that allow her more than an opportunity to dance a different vocabulary, she needs to find choreographers able and sensitive enough to fulfill her full potential by creating enduring works that are irrevocably stamped with her technical ability and personality.

Posted: June 27th, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Afterlight (Part One), Daisy Phillips, Daniel Proietto, Faun, James O'Hara, Lucy Carter, Made at Sadler's Wells, Mark Wallinger, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Michael Hulls, Nitin Sawhney, Russell Maliphant, Sadler's Sampled, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Thomasin Gulgeç, UNDANCE, Wayne McGregor | Comments Off on Made at Sadler’s Wells

Made at Sadler’s Wells, Sadler’s Sampled Festival, Sadler’s Wells, June 22

The Sadler’s Sampled festival is a welcome initiative by Sadler’s Wells to popularize dance that brings the concept of the BBC Proms to the theatre and adds a raft of programmed events in and around the foyer that ‘will provide a way in for audiences who many not be familiar with dance of any kind.’ There are four separate programs of dance over the two-week festival (ending July 7) beginning with Made at Sadler’s Wells that highlights three works the theatre has produced since 2005.

Russell Maliphant’s Afterlight (Part One) is all about the play between the dynamism of form in the choreography and the deconstruction of mass in the lighting and it takes a dancer who has the plasticity and precision to carve lines and shapes in space. I had the pleasure of seeing Daniel Proietto dance Afterlight (Part One) in 2010 and it was an extraordinary performance (his photograph appears in the program although Thomasin Gulgeç is on stage). For Made at Sadler’s Wells it is essentially the same work but it doesn’t quite match the unequivocal memory of something breathtakingly beautiful.

Afterlight premiered in October 2009 as part of the Spirit of Diaghilev program at Sadler’s Wells. Proietto brought to life the spirit of Nijinsky (which you can sense in the pages of Lincoln Kirstein’s superb collection of photographs, Nijinsky Dancing): introspective, sensitive, exotic. It was Maliphant’s inspired idea to marry the movement with music of similar qualities — the first four of Erik Satie’s Gnossiennes — and with Michael Hulls’ alchemy of light: choreography, music and lighting that compose a deeply satisfying unity.

Gulgeç appears with his back to us in carmine tunic and skullcap, spiraling his arms around his turning torso as if he is pressed against the glass that Hulls’ tube of light suggests. Gulgeç has the muscular ability to draw out the unctuous quality of the movement, but without quite the poetic, otherworldly element that I remember in Proietto’s performance. At the end of the second movement, he flings off his jacket in an uncharacteristically prosaic gesture and is now all in white for the third movement, which has a tone of pain or ecstasy whose ambivalence Gulgeç matches. Maliphant builds up the range of movement, exploring the air for the first time while keeping the spiraling, cutting, fluid turns that scythe through space so beautifully. The dappled lighting shrinks in the fourth movement while the dance continues to grow in elevation and expanse at the outer reaches of the solo piano, but the lighting gradually hauls Gulgeç back in to the jar until he disappears altogether.

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s Faun continues in the spirit of Nijinsky, delving into and reinventing his 1912 ballet, L’après-midi d’un faune. Cherkaoui’s choreography lays aside Egyptian fresco for free form, but he keeps the lithe, muscled and animal quality that James O’Hara embodies beautifully in his opening solo. The way he first appears, tightly rolled up under Adam Carré’s lighting, gives the impression he is still coiled around another’s body. To Debussy’s evocative score he unfurls, as if waking up on a lazy morning, shaking out the orgy of the previous night and imagining the next. Nittin Sawhney seamlessly interweaves his own score into that of Debussy to introduce the new object of the faun’s desire, Daisy Phillips. Where O’Hara is sinuous, Phillips is so flexible that her articulation verges on contortion; her facility undermines the feral sense of muscle and tendons and has the odd effect of leaving the partnership emotionless: muscular articulation, it would appear, is part of the language of dance and conveys emotional sense. However, the sheer invention of the interlocking choreography is not lost, nor is the sense of mysticism overlaid with the erotic in both choreography and music. Sometimes it is difficult to tell whose leg is whose in the intricate embraces and there are animal images of a mother cradling her young and a playfulness between the couple that is a pleasure to watch. At the end, Carré focuses a very bright spot on O’Hara as he reaches down to pick up Phillips from their feral sporting, but she recedes between his legs while he remains standing, suddenly imbued with moral sense, unsure what they had just experienced.

The link to Nijinsky in the first two works abruptly disappears in the third. Wayne McGregor’s UNDANCE, as its capital letters shrilly proclaim, is an elaborate conceit: some Muybridge-inspired exercises performed between Mark Wallinger’s two side boards with large painted letters ‘UN’ equals UNDANCE. Ha. Despite the conceit (though I did at first wonder what the political overtones could be), the opening is visually promising — a feature of McGregor’s collaborative works and of Lucy Carter’s lighting — but the promise fails to deliver and the end deceives: the restlessness of the audience as the performance progresses is palpable. Wallinger’s set design, including the UN boards, consists of a screen at the back of the stage on which the dancers are projected deliberately out of synch with the choreography on stage, either a step or two ahead or a step or two behind. As a statement in itself it is visually arresting, but in the context of UNDANCE, it simply multiplies what is essentially uninteresting. I don’t think Mark Anthony Turnage’s music helps the attention span, either. We are told that his score was inspired by a text written by Wallinger, which was in turn inspired by American sculptor Richard Serra’s Compilation of Verbs and the work of photographer Eadweard J. Muybridge. McGregor picked up on the Muybridge but his choreography is inconsequential in the company of his two mutually inspired artistic collaborators who appear to be doing their own thing in their own time.

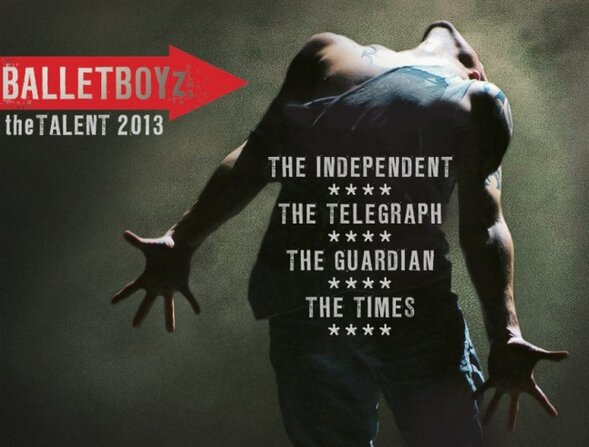

Posted: February 21st, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Arts Depot, BalletBoyz, Fallen, L'entrecôte Saint-Jean, Liam Scarlett, Michael Hulls, Michael Nunn, Russell Maliphant, Serpent, the Talent 2013, William Trevitt | Comments Off on BalletBoyz: the Talent 2013

BalletBoyz, the Talent 2013, Arts Depot, February 18, 2013

When I was living in Montreal there was I restaurant I enjoyed every now and then whose attraction was its single menu. If you wanted a lettuce and walnut salad to start, steak and chips as a main course and profiteroles for dessert, this was the place to go. The food was always good, the surroundings elegant, and you always had to book a table. It was called L’entrecôte Saint-Jean, it was centrally located on Peel Street and it’s probably still there and thriving.

Co-founders and artistic directors William Trevitt and Michael Nunn have adopted the same strategy for BalletBoyz: you know what is on the menu, the meat is fresh, the service is good, and it’s best to book in advance. I saw the company in 2011 when it was just The Talent and Russell Maliphant had reworked Torsion for the company with lighting by Michael Hulls. What has changed this year is the commissioning of a piece by Liam Scarlett, recently appointed Artist in Residence at the Royal Ballet and arguably ‘a hot ticket’. BalletBoyz has an unequivocal finger on the zeitgeist.

The short film projected before the show is at once an introduction to the brand and an ad for the product. The filming (by Nunn and Trevitt) is excellent at capturing a lively, smiling camaraderie among the dancers; youth, strength and beauty are the message. Also innovative is a filmed interview with each of the choreographers that screens before their respective works. Scarlett says that in his choreography for the Royal Ballet it is the women who drive the work. What will he make of the men? Can he teach them to drive? He seems unsure. As Serpent proceeds from languid, swan-like arm work and rippling backs through a series of duets, quartets and solos, male sinuousness and strength have by default taken the wheel, but the snake seems satiated and ends up going to sleep in the position in which it started. Scarlett seems satiated, too, seduced perhaps by the hypnotic sameness of the BalletBoyz physique into creating a homo-erotic conflation of the myths of Icarus and Narcissus that raises the display of male bodies to a level of advertising but never stays far off the ground. Neither does the pastiche of Max Richter’s saccharine tracks from Memoryhouse and neither, surprisingly, does the lighting of Michael Hulls, which seems a little uninspired here (there was a delay of 30 minutes in the start of the show due to ‘technical problems’, so perhaps he was not able to deliver what he had intended). Choreographically, it is not so much what Scarlett has been able to do with BalletBoyz, but what they have been able to do with him.

Maliphant has worked with Nunn and Trevitt and BalletBoyz for 11 years, so he knows what’s expected. His choice of music by Armand Amar makes sure Fallen starts on a stronger beat than Serpent, and the boyz are put through their paces on the floor (where it is always difficult to see them) and in the air as they climb and spring up on each other but there is still a sense of not letting too much hang out, keeping the body beautiful in its sculpture form (more of Rodin’s influence, perhaps) with a circular, inward-focused choreographic development. No single dancer stands out; the ten men are unsurprisingly uniform in appeal, dressed in t-shirts and combat pants in battle green, echoing the palpable element of chic violence. Michael Hulls’ lighting design has more punch here than in Serpent, and has reminders, if not enough evidence, of how effective his lighting can be.

The printed program handed out to the public contains good publicity images, headshots of the 10 boyz on a first name basis, a list of tour dates and some wicked hyperbole like ‘This is dance at its most riveting and fearless. Talent? I should say so” from the Independent on Sunday. It is more like a flyer than a program. Perhaps it is the flyer. If you want to know what works are being danced, however, you have to buy a glossy program but surprisingly there is nothing in it about the works — apart from the credits for choreography, music and lighting — but lots about the company and the dancers: BalletBoyz seems to be all about image over content. The glossy program is prefaced by a high-pitched message to ‘Dear Audience’ signed, ‘love Michael and Billy’. So what is the message? ‘Welcome to our latest show…which sees us carry on from where we left off last season…’ The menu hasn’t changed, but looking at the 29-date tour, BalletBoyz, like L’entrecôte, have clearly got a winning formula.

Posted: October 19th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aakash Odedra, Akram Khan, Andy Cowton, Constellation, Cut, In the Shadow of Man, Jocelyn Pook, Michael Hulls, Olga Wojciechowska, Rising, Russell Maliphant, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Willy Cessa | Comments Off on Aakash Odedra: Rising

Aakash Odedra, Rising, Pavilion Dance, October 18

Before Aakash Odedra performs the three contemporary works on the program, he demonstrates his dance roots in Kathak. Nritta, meaning pure dance, is a variation he created for himself and for which he arranged the classical Indian music. In my previous post, I mentioned that dance is expressed in the intellectual, the physical and the emotional bodies. Here in Nritta, Odedra manifests them all in perfect harmony within the complex rhythm of the music. As he writes in the program notes, ‘Here the movements of the body do not convey any mood or meaning and its purpose is just creating beauty by making various patterns and lines in space and time.’ It is pure dance.

Just perceptible in the smoky apse of light is a figure with his back to us, dressed in loose, grey cotton kurta and pants, his body still but for his arms and hands rising slowly, palms and gaze turned upwards as if offering a libation to the gods. The dance develops with dizzying, virtuosic turns – there is something of a Dervish in Odedra – and his lightning movements of the torso and arms make those statues of Shiva with multiple limbs make sense. How else can you capture this kind of movement in a statue? I had always thought of Kathak as grounded, with upward movement expressed in the body as an opposition to the energy directed into the floor, but the name Aakash means sky, and upward for Odedra means airborne: it is part of his personality, a trait his teacher in India recognized and encouraged. He has a slight frame, taut and elongated, so there seems to be no apparent force in his dance; what comes across is his love and thrill of movement and his freedom to jump and turn effortlessly around a still point. It is the physical expression of being in the moment.

Odedra does not come to contemporary dance through training in contemporary dance. He comes to contemporary dance through his training in Kathak. This makes his collaborations with Akram Khan, Russell Maliphant and Sid Larbi Cherkaoui a unique occasion. Khan has already developed a remarkable body of work from the same dance roots, so creating a solo on Odedra is a fast track process to a place way beyond the beginning. In the Shadow of Man is indeed a work that challenges Odedra in ways he may never have imagined, but his sensibility and integrity, not to mention his innate virtuosity, rise to the challenge. In the program notes, Khan muses on their shared Kathak tradition: ‘I have always felt a strong connection to the ‘animal’ embedded within the Indian dance tradition. Kathak masters have so often used animals as forms of inspiration, even to the point of creating a whole repertoire based on the qualities, movements, and rhythms of certain animals. So, in this journey with Aakash, I was fascinated to discover if there was an animal residing deep within the shadow of his own body.’ I don’t think there is any doubt that he found it, and the way Odedra reveals it is remarkable.

The opening image is difficult to make out, a shell or shield of an insect that is alive in that expressionless way insects busy themselves with the act of living: a movement of the eye, a leg, an antenna. But as the lighting of Michael Hulls gradually reveals this shield, we see it is Odedra’s crouched, naked back, and the insect eyes are his scapula rippling under his skin and the antennae his elbows. Jocelyn Pook’s score is suddenly riven by a piercing shriek from Odedra taken on the inbreath, scorching the lungs. He comes alive, unfolding like a wild man and stretching out his angular arms and legs like an emaciated saint stretching. The lighting picks out these body shapes, following the tearing movements of this hunter-gatherer, mouth gaping and blind eyes engaged. As in Nritta, we see the velocity of the turns, the arms whipped into the form of a double helix, and then the stillness. The insect develops into a loping monkey, to which the hissing and shrieks now belong, as do the whirling arms at the limits of Odedra’s circling torso, and the arching backbends that put his wild eyes upside down staring at us: traits of the atavistic figure consumed by the animal Khan has embedded – or revealed – in him. Pook’s score adds a sense of calm and order, rounding off the corners without disturbing the angular, feral nature of the beast. What gives this performance an otherworldly quality is the lack of any ego; Odedra has given himself over to the dance, and his bow at the end is one of genuine humility.

In Russell Maliphant’s Cut, Maliphant doesn’t so much create movement for Odedra as structure it. We see Odedra’s undulating, double-helix arms, his ability to rise from the ground as if pulled up by an invisible thread, his lightning dynamics, his ability to spin and his generosity of spirit. What distinguishes Cut – and gives it its name – is that Maliphant has Odedra dance with the light patterns of Michael Hulls which cut his body into zones of light. Hulls is a visual magician, creating a virtual scrim of light and smoke through which Maliphant thrusts and weaves Odedra’s movements, first his hands and arms and later his full, whirling body. The lighting also supports Odedra’s gestures, as when he pushes down magisterially on two columns of black light that are the vertical shadows underneath his own hands. A third element is Andy Cowton’s score, which is as intimately related to the choreography as the lighting. When Hulls’ triangle of light takes on three dimensions, opening up a vista of latticed blinds on the floor, there is a suggestion in the music of the blinds opening and closing as Maliphant contrasts Odedra’s crawling motif with the horizontal bars of light. Hulls rolls up the blinds leaving Odedra in silhouette in open space, and then raises the lighting level so only his skin is visible as his clothing blends into the smoky light. The final sequence is pure Odedra, whirling fiercely downstage across the blinds and arriving at a stillness in which he grasps the shadows of his hands and pushes them down once again, keeping his dark gaze on us, as he turns up his palms and closes his fingers slowly into a fist.

The order of the program is decided more by the technical aspects of the lighting than by a considered approach to the choreographic content: a little bit too much of the lighting tail wagging the choreographic dog. The last work, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s Constellation, is the most mystical of the three, and belongs more in the middle than at the end, except for its lighting demands. It is also the work in which there is less of Odedra’s own movement vocabulary and more of Cherkaoui’s conceptual framework: a constellation made up of patterns of sound and light with Odedra as the locus, an ‘astral body generating its own rhythms and luminosity.’ The rhythms are provided by the lovely score of Olga Wojciechowska, and the luminosity by Willy Cessa’s suspended light bulbs of differing intensities that provide the only illumination for Odedra’s motion. He is more a presence in Constellation than a performer of Cherkaoui’s movement phrases. At one point Odedra swings a single bulb in front of his head that illuminates the alternate sides of his face as it rotates, like two phases of the moon. Constellation is a meditation on space and spirituality, and Odedra provides a performance of mystical serenity. Towards the end he sits in meditation and instead of Cessa’s lights fading to black at the final moment, they all increase to full illumination. How appropriate.