Posted: January 28th, 2016 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Alys North, Anne Burgi, Charlie Dearnley, Claire Denis, Daniele Sablone, Jean-Pierre Nyamangunda, Lizzie J Klotz, Maria Fonseca, Resolution! 2016, Roland Barthes, Sia Gbamoi, Tindersticks, Viviana Rocha, What Is Written Dance Company | Comments Off on Resolution! 2016, performances on January 19

Resolution! January 19: Lizzie J Klotz, Maria Fonseca, What is Written Dance Company

Alys North and Charlie Dearnley in To Suit (photo: Camilla Greenwell)

I first saw Lizzie J Klotz’s To Suit at The Galvanizer’s Union pub in London on the Kaleidoscopic Arts Platform. It was a well-formed miniature in an intimate setting. When Klotz talked of expanding it for Resolution! I wondered how something that was already complete could be lengthened without unbalancing it, but it has grown into a well-formed miniature in a larger setting, just as warm and just as rich. The lighting by Michael Morgan has helped keep the space intimate, but Klotz and her two performers (Charlie Dearnley and Alys North) have remained true to the spirit of the work and to the relationship between them; its warmth and sense of humour has Made in the North all over it. One of To Suit’s beauties is that it doesn’t have the self-conscious pose of a dance piece; Klotz writes that it was ‘developed through an investigation into human communication…[drawing] comparisons to animal courtship rituals, specifically exploring the behaviour of birds.’ The edges of the communication dissolve into dance and the dance dissolves into the communication. It helps that both Dearnley and North do not come across so much as dancers as two people who move (and speak and sing) their relationship. Dearnley at the beginning goes through a series of gestures in silence that suggest a human agency but when North arrives clutching a bundle of rich-coloured clothes the subsequent communication between them is expressed through an overlapping of text (by Dearnley), bird cries, social dance, over-dressing, cross-dressing and ecstatic jumps. We infer the relationship between the two from their actions in the same way we can feel Johann Sebastian Bach’s music (which Klotz uses to great effect) through its internal structure; the emotions come out of the music and the dance. All that remains is to end To Suit as simply and effectively as it starts.

IDADE in Maria Fonseca’s native Portugese means age, and is the name she has given to her work exploring the phenomenon of ageing through the relationship between herself and Anne Burgi. The rather dark, symbolic opening suggests a mother-daughter relationship as Burgi stands holding a length of coiled material that ends in a shaded pile on the floor. The pile unwinds into Fonseca who unravels the umbilical cord, winds it around her head like a tribal headdress (reminding me of Steve McCurry’s famous photograph of the Afghan girl) and dances with all the sinuous vitality of youth to a Claire Denis film score played by Tindersticks. Fonseca calls growing old ‘an infinite dance of transformation’ but with Burgi’s reading a text about ageing and a long interview in which Fonseca asks questions and Burgi answers, the transformation takes on a rather too dialogical aspect. IDADE thus has a double identity: a theatrical performance with imagination and symbolism, and a conversation that has neither. There is too little of the former and too much of the latter to make a coherent work.

What is Written Dance Company performed Dialect of War at Emerge with three dancers (Jean-Pierre Nyamangunda, Viviana Rocha and Sia Gbamoi). Here it is expanded to a fourth dancer (Daniele Sablone) but either the choreographic elements of expansion or the space has diluted some of the power I remember. Described as ‘the story of a warrior tribe whose lives are brutally disrupted’, the opening scene of four warriors at rest to a recording of battle sounds is too ingenuous, especially when they all raise their knees on cue. The four dancers can evince a powerful energy but too often they appear unable to get into gear. There is a slow, menacing beginning to a duet between Nyamangunda and Gbamoi but as soon as the music begins they suddenly speed up. We know this is a theatrical representation of conflict and violence, but such lapses of dramatic continuity make the artificiality apparent. As Roland Barthes wrote on the spectacle of street wrestling, ‘what matters is not what [the public] thinks but what it sees.’ We want to believe, and at Emerge the dancers convinced me of their state of mind but here, for the most part, it was not as evident. This is all the more essential as What is Written Dance Company is presenting a subject that is beyond our imagination; to make it work, they have to go beyond our imagination into the realms of both the human and the animal to convey the palette of emotions, and then some. I felt it before, but something too civilised has set in to dilute its expression.

Posted: January 27th, 2016 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Photography | Tags: Edward Watson, Rick Guest, Sergei Polunin, What Lies Beneath | Comments Off on Rick Guest, What Lies Beneath

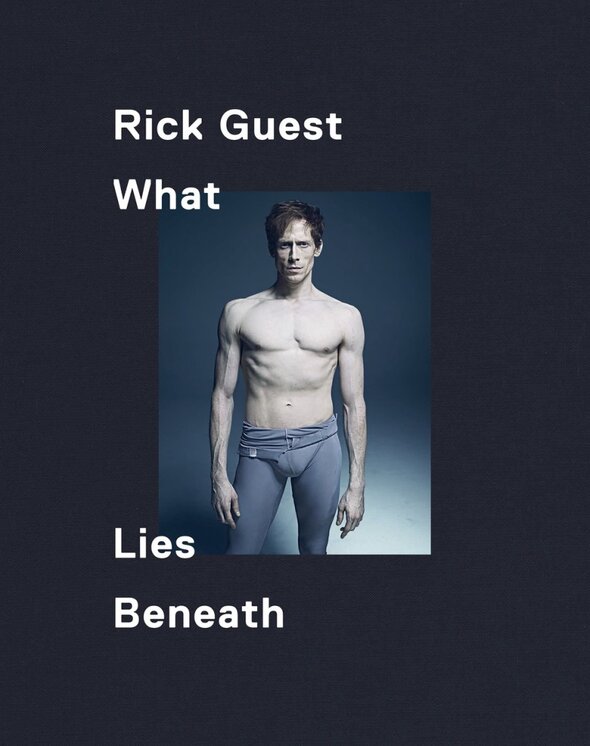

Rick Guest, What Lies Beneath & The Language of the Soul

Still and moving images are the only ways of getting close to representing a memory of dance and it is only with the relatively recent development of recording techniques that the moving image has reliably captured artists in performance. The still image has been around for a lot longer, long enough, for example, to admire the series of photographs of Vaslav Nijinsky by Baron Adolphe de Meyer begun in 1911. In his sumptuous book of these photographs, Nijinsky Dancing, Lincoln Kerstein claims ‘Nijinsky is in fact the first dancer in history who seems to have collaborated consciously with a photographer on the level of art.’ Until the arrival of the 35mm camera and more sensitive film, the studio was where dancers and photographers would collaborate on a shared aesthetic but as soon as the technology was available dance photography turned its attention to the performance shot. Photographs of Royal Ballet dancers over the years show both kinds of images by such notable photographers as Gordon Anthony, Cecil Beaton, Anthony Crickmay, Michael Peto, Zoë Dominic, Keith Money, Lord Snowdon and Leslie Spatt while today you are likely to see glossy performance shots in the program by Johan Persson or Bill Cooper while in the contemporary sphere Hugo Glendinning and Chris Nash have developed a distinct style of expressive dance portrait that borrows from both performance and the studio. But at the end of last year fashion photographer Rick Guest released two self-published books of dance photography that eschews the performance for a more personal approach. Guest was introduced to dance by his wife some 15 years ago — he remembers Irek Mukhamedov in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet — and found his way back to The Royal Ballet with a commission to photograph principal dancer Edward Watson. From this grew the first book, What Lies Beneath, for which Watson is the muse and in which Guest’s fascination with and admiration for the dancer’s ethos finds expression in large-format portraits of an extended cast from The Royal Ballet, English National Ballet, the Danish National Ballet, Dresden’s Semperoper Ballett, Wayne McGregor’s Random Dance and Richard Alston Dance Company.

To concentrate his (and our) attention on the person Guest removes the locus of these photographs. All that outwardly signifies the dancer is the clothing, which is a study in itself: tattered, worn-out warmers that hang, it has to be said, with remarkable effect on these honed bodies or lovingly stitched repairs on a favourite unitard — as in the portrait of Melissa Hamilton that reveals the unequivocally trained body beneath its delicately scarred covering. In stripping the dancers of their performative role Guest reveals the enigmatic presence within. They are suspended not spatially (there are some fine examples of those, notably of Sergei Polunin suspended on an invisible cross) but psychologically; some have the confidence to be themselves in front of the lens, others feel the need to pose, giving the photographer their ‘best angle’ or baring their extraordinary physique for all time. But many are revealing of a quality that transcends description, of a neutral mien that is like the clay before it becomes a sculpted form (notably Svetlana Gileva and Julia Weiss of Semperoper Ballett). In other portraits there is an earthy quality that contrasts with the stage presence. Marianela Nuñez has a weightless, ethereal quality on stage but here she is quintessentially a woman with gravity in images whose locus is somewhere between the living room and the studio.

The dancers return our gaze — the gaze of the photographer — in response to a dialogue we cannot hear. Watson, like Hamilton, allows the gaze in, without any sense of defense. Eric Underwood looks into it as in a mirror; Yenaida Zenowsky and Yuhui Choe match it enigmatically, Alison McWhinney wistfully; Sergei Polunin meets it head on and Olivia Cowley gently deflects it. In Tamara Rojo’s reflective pose her eyes look away and down, preoccupied with her own world that is encapsulated within her superbly honed lines.

It is interesting to compare the physicality of dancers across the different companies — the effect of respective repertoires, physical conditioning and company culture. At Semperoper, for example, the dancers’ bodies appear more at ease and their clothing neatly utilitarian yet the traces of their profession are still apparent. What Guest has captured, essentially, is the way embodied classical training and the experience of performing express themselves in the eyes, in the posture and gesture of the dancer’s body. At the current exhibition of Guest’s photographs at the Hospital Club in Covent Garden, where the portraits are almost life-size, it is the eyes that engage directly with the lens and the spectator so they seem to follow you around the gallery.

In 2010 Guest saw Jane Pritchard’s Diaghilev exhibition at the V&A where his interest in fashion overlapped with his fascination for dance. The second compilation of photographs, The Language of the Soul, includes the same dancers as in What Lies Beneath but in more active poses partnered with his familiar world of fashion. ‘Some of the images are pure dance, some more fashion and some more photographic in nature,’ he writes. In both the dance and fashion portraits there emerges, unlike in What Lies Beneath, a performative quality which in certain cases is transformative.

There is a lovely anecdote in Sarah Crompton’s afterword to What Lies Beneath about Antoinette Sibley’s first glimpse of Galina Ulanova in rehearsal in 1956 that sums up the kind of place these dancers take up in Guest’s book:

“This old lady got up from the stalls. We thought she was the ballet mistress. She was saying something to the dancers and then she went and stood on the stage up on the balcony and she still had these awful leg-warmers on and, well, she looked 100. And then she suddenly started dreaming. And in front of our very eyes — no make-up, no costume — she became 14. I have never seen anything, in any sphere, as theatrical as Ulanova getting up in her scrubby old practice clothes…with her grey curly hair and becoming Juliet….From then on…I knew you could be…an amazing ballerina…and not perfect. Perfection was not part of Ulanova’s scene at all. She was human. It was to do with transformation.”

There are no ‘old ladies’ of either gender in the book, but some of the portraits reveal this transformative ability, notably in Sergei Polunin. He is singing in his portraits; he has something to sing about and so does his body. He becomes someone else. It is also good to see the performance photograph of Johannes Stepanek in an image I have seen in a Royal Opera House program without finding a credit.

The more I look at the photographs in these two fine compilations the more I am drawn into them. It is too easy to take the performance image for granted: to acknowledge the dancer without seeing the person. What Guest does is to first decontextualize the dancer and then to show each one in a refreshingly unfamiliar light with the immediacy of bringing the viewer into the same room to share his sense of admiration and awe.

http://rg-books.com/products

Posted: January 25th, 2016 | Author: Ian Abbott | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Akram Khan, Annie Leibovitz, Ching-Yien Chien, Christine-Joy Ritter, Julian Charrière, Karthika Nair, Lloyd Newson, Roundhouse, Ruth Little, Tom Stoppard, Until the Lions | Comments Off on Akram Khan, Until the Lions

Akram Khan Company, Until the Lions, January 19, Roundhouse, London

Ching-Yien Chien, Akram Khan and Christine-Joy Ritter in Until the Lions (photo: Jean-Louis Fernandez)

“The truth is like a lion; you don’t have to defend it. Let it loose; it will defend itself.” Augustine of Hippo

We do not encounter performances in isolation and so to write about them without context tells only part of the story. Earlier on the same day I visited two exhibitions: WOMEN: New Portraits by Annie Leibovitz at Wapping Hydraulic Power Station and For They That Sow The Wind by Julian Charrière at Parasol unit foundation for contemporary art.

As an architect of mood Khan (and his creative collaborators) clearly frames our arrival into the Roundhouse with a low grumbling, electronic rumbling soundtrack and a 15m wide tree trunk splatted across the stage. Fissures run through the trunk and act as a future echo for the scenographic finale that lingers in the mind long after you’ve left the auditorium.

Until the Lions (the performance) is distilled from a collection of poetry by Karthika Nair (of the same name) who amplified the narrative and shone a light on some of the minor female character’s from the original hindu epic The Mahabharata (in which a teenage Khan performed in Peter Brook’s seminal performance). In 1966 the playwright Tom Stoppard excavated two minor characters (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern) from Shakespeare’s Hamlet and injected them with life and framed them within a play of their own. The process of ekphrasis is one that Nair practices regularly and she’s previously worked with Khan as a writer on DESH:

“Akram is not interested in my poems as poems, he is very clear that it is the story or mood, the content which he will mould into his language or languages for stage: movement and visuals and music.”

Khan and dramaturg Ruth Little attempted to stretch and deliver a slender narrative of male domination and female vengeance over 60 minutes with three dancers (Akram Khan, Ching-Yien Chien and Christine-Joy Ritter) and four musicians (Sohini Alam, David Azurza, Yaron Engler and Vincenzo Lamagna) with little success.

“Don’t ask me who’s influenced me. A lion is made up of the lambs he’s digested, and I’ve been reading all my life.” Charles de Gaulle

My ears feasted on a driving and insistent live percussive score — an evocative vocal intensity, bordering on the shamanic, intoxicated me with a fervour, tension and delicious agitation; but my eyes nibbled on unimaginative repetition, 2D characters who didn’t want to connect with me and chasms of flabby, empty space. I felt little sense of drama, found no invention or choreographic hunger and left with a jarring sense of disappointment at this mismatched marriage of sound and vision.

There were too many examples of circumference running and walking which drained any pace and sagged any momentum being created by the urgent and cohesive soundtrack. As the performance developed I saw little nous or demonstration of the craft required for performances in the round. The centre of the stage is the weakest point for a performer as it’s here that half the audience cannot see the front of the body or face; yet Khan focused so much choreographic and illuminated action on this section of the stump.

However, there was a moment (around two thirds of the way through) when I felt an equality; the compositional and choreographic power aligned as Ritter began to take on a new form to vanquish her male nemesis. Here she writhed, scuttled and possessed arachnid qualities, totally inhabiting the movement, whilst my ears were possessed with voodoo screeches and relentless twitchy beats — it was in this moment I was magnetised; I zoomed in and wanted more. As a performer Khan was consistently rigid, restive and demonstrated little Kathak fluidity and I couldn’t understand the intention behind his own choreographic choices as it served only to highlight the lack of depth in the characters and narrative.

“A lion among ladies is a most dreadful thing” William Shakespeare

Maybe Khan should follow in the footsteps of Lloyd Newson who recently announced he was taking a break. We know there is richness to be mined in Khan’s older work as exemplified by Chotto Desh (a work based on Desh but made for young people and expertly directed by Sue Buckmaster) which had no creative input from Khan and is currently touring under the banner of his company. The process of ekphrasis is already being practiced by Karthika Nair; why doesn’t Khan offer existing work to other choreographers and let them re-author it? An artist cannot constantly produce success after success and should not be beholden to a dance industry which demands new and more; otherwise fields become fallow, trees cannot grow and kittens will not become lions.

The Leibovitz portraits of Misty Copeland, Aung San Suu Kyi and others provided examples of female intimacy, power and drama that were authored by a woman whilst Charrière offered adventurous interpretations of how to merge past and present. Until the Lions explored similar territories and with the dance industry undergoing some very public reflection on the division of opportunities, commissions and performances between men and women it’s important to see how other artists are examining a similar terrain.

Posted: January 24th, 2016 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Calle Leganitos, Family Honour, Jack Philip, Kwame Asafo-Adjei, Laurence Louppe, Oihana Vesga Bujan, Pirenaika Dance, Psychoacoustic, Resolution! 2016, Spoken Movement | Comments Off on Resolution! 2016, performances on January 16

Resolution! January 16: Jack Philp Company, Pirenaika Dance, Spoken Movement

Elly Braund and Nancy Nerantzi in Pinenaika Dance’s Calle Leganitos (photo: Pierre Tappon)

Jack Philp’s Psychoacoustic is a collaboration between neuroscience, sound and movement to ‘explore the body’s and brain’s response to sounds around us in light of particular emotions.’ Philp sets the context with a visual presentation of a mix of jarring sounds we might experience on a daily basis: pedestrians, traffic, construction, and social media. Gaia Cicolani stands immobile in front of the screen but her tensed hands and fingers prelude a growing muscular contraction throughout her body in response to the cacophonous input (audience brains are probably doing something similar but the seated bodies do not carry the movement through in the same way). By contrast, Linda Telek responds calmly to the more lyrical passages in Ben Corrigan’s acoustic environment but the reactions of both dancers fall within a narrow range of predictable gestures. It is only in their interaction with Clémentine Télesfort that the theme begins to develop as if they are reenacting the processes of the brain undergoing contrasting acoustic patterns. It is neuroscience, however, that has the leading role and the stage is rooted in the laboratory. Philp describes Psychoacoustic as ‘a culmination of the primary stages of an ongoing research project’, which translates as ‘the end of the beginning.’ In its further development Psychoacoustic might benefit from employing a less literal approach to movement and giving it less of a reactive role than an equal partnership in the collaboration.

Pirenaika Dance is Oihana Vesga Bujan, a dancer with Richard Alston Dance Company. Calle Leganitos, which Pirenaika Dance presented at Resolution!, is the first public sharing of Vesga Bujan’s choreography. Although she herself is an accomplished dancer, she has created her work on two other dancers in the company, Nancy Nerantzi and Elly Braund. The starting point is an odd one but with happy consequences: a Victor Borge performance of A Mozart Opera in which he characteristically reduces the cast and plot to a banal, farcical tale. Vesga Bujan sets off in the other direction with her two dancers to find ‘a relevant dance’ to an adagio, an allegro and a rondo for strings by Mozart. The dancers ‘will dive into the unknown…towards a place far from the glittery or the mundane…’ which is exactly what they do. Nerantzi and Braund are like spirited twins let loose on the rhythms and nuances of Mozart’s music that with Vesga Bujan’s help transport them to new levels of exhilaration. Even when Vesga Bujan plays with silence she keeps the musical line in motion with her innate musicality and lyrical sense of movement. What she adds to the dance is a lively gestural sense*; her gestures, drawn from daily life, amplify and qualify the dance in a way reminiscent of Jiří Kylián’s choreography. Like Kylián she finds through gesture new dynamic shapes, and the new shapes lead to new connections that form refreshingly new phrases and choreographic punctuation. For a first public work, Calle Leganitos is remarkably mature.

Kwame Asafo-Adjei’s Family Honour to a score of the same name by Simon Watts is a production of Spoken Movement, which is an apt description of the way Asafo-Adjei performs. His movement speaks with an intense physical articulation in the service of a narrative, the history of a father whose memory lies deep in regret and sadness. The work is full of symbolism to which Asafo-Adjei pays precise attention as if performing a ritual. He picks up a book from his desk and peremptorily tosses it out as if the written word has no place here. He talks about his mother as a ‘very, very, very wise woman’ but when he mentions his father he falls silent, looking away with a pain that has no words. He communes with his invisible mother, his source of strength, then fails once again to speak about his father. Instead his frenetic hands on the desk go through the actions of erasing, cutting, re-ordering and then with his whole body he digs out the traces of his memories on the floor in an extended, contorted solo, hammers them out with his muscled arms and shoulders until he sits once again at the desk, exhausted and exorcised. He lays his body on the desk and breathes a final, muffled incantation for his ears alone. Asafo-Adjei is a compelling performer, but what makes Family Honour disquieting is the inseparability of this life story from its theatrical expression.

* According to Laurence Louppe (in her Poétique de la danse contemporaine), a gesture is the visible emanation of an invisible physical source that nevertheless conveys the intensity of the entire body (‘Le geste est avant tout l’émanation visible d’une genèse corporelle invisible, mais porteuse de toute l’intensité du corps global.’)

Posted: January 20th, 2016 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Agnieszka Dolata, Alex Judd, Aneta Zwierzynska, Animal Radio, Book My Face, Durgesh Srivastava, Here Body, ISH by moi, Maga Radlowska, Neil Emmanuel, Neus Gil Cortés, Resolution! 2016, Sirens, The Place | Comments Off on Resolution! 2016, performances on January 15

Resolution! 2016, January 15: Animal Radio, ISH by moi, Neus Gil Cortés

Publicity image for Neus Gil Cortés’ Here Body (photo: Patricio Forrester)

Some subjects just don’t seem to share common ground with the choreographic side of dance and social media is one of them. Animal Radio’s Book My Face begins with a powerful visual image on a screen of two large-scale faces (of the two dancers, Maga Radlowska and Aneta Zwierzynska) undergoing cartoon-like transformations (photography by Agnieszka Dolata and filmed by Neil Emmanuel). The faces endlessly morph from one tic to another, one expression to the next, but the idea gets carried away; it becomes a show in itself, lasting the entire length of the work without playing more than a peripheral role in it. The drive behind Book My Face is an exploration of how ‘virtual identity affects the inner instinctive animal in us’ and ‘the extent to which the identities we inhabit impact on our movement patterns.’ Do they? It seems to be a case of a choreographic fusion of Animal Radio’s contemporary dance, capoeira and contact backing itself into a concept. The only connection is between the dancers and the live rhythmic input of musician Alex Judd. It might be worthwhile to put the concept and the visuals aside and start again with the dancers and the music to see where that might lead.

ISH by moi’s Sirens is another kind of animal altogether. Ishimwa Muhimanyi uses a zoological analogy to establish his premise: ‘Visibility exposes an animal to the risk of attack from its enemies, and no animal is without enemies. Being visible is therefore a basic biological risk; being invisible is a basic biological defence. We all employ some sort of camouflage.’ The opening film of the striking Muhimanyi in a long black wig, bright red pants and matching trainers drinking a milky white substance from a bowl on a white floor is a defiant statement of visibility. If he is being provocative it is with a siren’s beguiling sense of humour. In the same outfit he backs on to the stage in a narrow rectangle of light, rippling and undulating with unabashed showmanship before dropping his disguise to start a cabaret-like monologue on coming to grips with and overcoming fear (in the form of a black latex mask on a stand whose potential for camouflage he rejects). His text is candid and amusing (an irresistible combination) and his gestures seem to derive from the same impish source. By the end Muhimanyi has established his sense of self without imposing it; instead, he draws us into his world, our camouflage in disarray.

I have seen three pieces by Neus Gil Cortés (most recently at Emerge Festival) and while each has been quite different there is a core that is consistent. She has that ability to evoke emotion through a minimum of means. In Here Body she puts together traces of memories and expresses each of them in her movement, one after the other, sometimes overlapping, creating a collage of gestures, acts, and stillness that together form the reality she is remembering. As in memories, there is space and time in her work and she allows us the space and time to engage our imagination to draw us in to her remembering without giving us a narrative map. At the very beginning we see an empty wooden rocking chair in the spotlight and just clear of it, in the half-light, we see Gil Cortés lying on the floor, her head, long languid arms and legs in a state of suspension, floating. In her program notes, she writes that Here Body ‘explores feelings and fears around death and decay.’ These feelings, so I learned later, are the result of two concurrent events in Gil Cortés’ life: a loss of faith and the death of her beloved grandmother. I mention it not because they provide context vital to an understanding of the work, but because I am fascinated by Gil Cortés’ process of transforming memory into choreography, finding the emotion in motion and fusing the two in their shared meaning. This is what she does so well. Here she improvises to texts read by Jane Thorne that comprise random funerary memorials found on the Internet. However, at the end of Here Body Gil Cortés unravels part of the mystery by introducing a figure in the form of Durgesh Srivastava who represents her late grandmother. As a choreographic device it is risky, making visible what the invisible presence in the rocking chair had evoked. It is a concession to materialism, but Srivastava provides one of the crowning moments of the work. On the accent of ‘ok’ in a song (Darling Deer by BRIXIA) about the acceptance of death and decay, her arms trace a circle over Gil Cortés’ head like a prayer and continue upwards. It is such moments that have the power to heal.

Posted: January 15th, 2016 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Alexandre Hamel, Dance Umbrella, Jasmin Boivin, Le Patin Libre, Lucy Carter, Pascale Jodoin, Samory Ba, Taylor Dilley | Comments Off on Le Patin Libre, Vertical

Le Patin Libre, Vertical, Somerset House, January 13, jointly presented by Dance Umbrella and Somerset House

A Dance Umbrella Commission in partnership with National Arts Centre, Canada and Theatre de la Ville, Paris. Research supported by Jerwood Studio at Sadler’s Wells and Dance Umbrella

Le Patin Libre at Somerset House (photo: Alicia Clarke)

When I first saw Le Patin Libre at Alexandra Palace in Dance Umbrella’s 2014 festival I arrived late and saw only the latter part of their first half, Influences. The second half was Vertical which is the work Dance Umbrella has brought back to London for a limited run on the skating rink in its front yard at Somerset House. Renegade skaters, cutting edge ice dance performance runs the publicity with a smile. Watch the award-winning Le Patin Libre (they won the Total Theatre & The Place Award for Dance at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2015) carve the ice, with their signature blend of technical skill and cutting edge style (at the Quebec Delegation reception Emma Gladstone added that the group had also a strain of bloody-mindedness for forging ahead with their project despite criticism and jeering from hockey players and ice dancers at home in Montreal). Their mix of intricate footwork, wit, speed and grace pushes the boundaries of what is physically possible and carries ice-skating performance into the 21st century. There’s certainly some disambiguation to be done to separate the skating of Le Patin Libre from other forms of dancing on ice. Translating the company name — free skating — is true to its origins but doesn’t do justice to the artistic endeavor of the group and ‘artistic free skating’ sounds like an Olympic category. So until some apt description can be found the only way to know what it is they do is to see them perform. They have some work to do as well; while all five (Alexandre Hamel, Taylor Dilley, Jasmin Boivin, Pascale Jodoin and Samory Ba) dress casually (no glitter to be seen) and take care to present their work without the trappings of figure skating, they are not averse to feats of skating virtuosity, as if to reassure us they are former professional skaters. They don’t need to. The articulated solo by Ba, Jodoin’s sensuous spirals and the long, sweeping, swooping, interweaving patterns of the quintet up and down the ice are what mark the originality of Le Patin Libre: understated artistry that could not be achieved without their level of skill.

It’s not just the ice but the space that Le Patin Libre transforms with their art. Seeing what they did at Alexandra Palace was a revelation of sheer volume; at Somerset House the space is, paradoxically for an open-air rink, constrained, perhaps by the monumentality of Sir William Chambers‘ neoclassical architecture with its ice-sugary lighting in shades of blue and pink. By comparison with the performance at Alexandra Palace, Vertical at Somerset House seems more of a sampler, welcome nonetheless and well worth seeing, but not fully representative of what this quintet can do. Their ideas need the freedom and distance of the largest indoor rinks because their lines and speed and dynamics — like a flock of long-legged birds in formation — can best be appreciated on that scale. Although the development of the group originated on outdoor rinks in Montreal, the performers feel more at home navigating at high speed the vast indoor spaces of skating rinks where the theatrical effects (here by Lucy Carter) of lighting and haze, moreover, are not subject to the vagaries of outdoor weather.

Inserted like an unofficial preview into the opening of Vertical (as Alexandre Hamel told me after the performance) are some ideas the company is developing for a new show which hint at a form of minimalism, enhancing the geometry of patterns with the glistening lines of the skaters’ trajectories to expand our sense of space and time. While Vertical and Influences have gone a long way towards creating a new spatial dynamic of dance, this new work has the opportunity to consolidate the form. Perhaps by then it will have a name.

There are eight more performances of Vertical at Somerset House on Friday January 14 at 18h30 and 20h00 and on Saturday and Sunday January 15 & 16 at 18h30, 20h00 and 21h30.

Théâtre de la Ville will be presenting Le Patin Libre in Vertical Influences at the Patinoire de Bercy in Paris from 14 to 17 June.

Posted: December 30th, 2015 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: David McCormick, Mark Coniglio, Michael Mannion, The Chapter House, Zoi Dimitriou | Comments Off on Zoi Dimitriou, The Chapter House

Zoi Dimitriou, The Chapter House, Laban Theatre, November 26

Publicity image for Zoi Dimitriou’s The Chapter House

Watching Zoi Dimitriou’s The Chapter House at Laban Theatre recently is like taking part in a formal ritual. It is a calm work, lit to stillness by Michael Mannion and dressed in planes of white and lines of wire; an abstract world punctuated by the stormy lyricism of the musical score formed of pieces by Pluramon, Conlon Nancarrow and Caccini.

In such an austere and well-lit environment every detail of the performers’ gestures is magnified, which lends itself well to the nature of this solemn enquiry into the nature of creation. As Dimitriou asks rhetorically in the program note, ‘…what does it take to make (or remake) an art work in and for the digital age?’

The Chapter House is a kind of retrospective with a twist. It began as an idea to revisit five of Dimitriou’s past creations to assess the path she had taken and where she found herself at the end of it. It was an artistic and intellectual act whose prime concern was evaluation rather than creation but in inviting media/performance pioneer Mark Coniglio to help her with the documentation of her project she discovered in the process of recording her five ‘chapters’ that the transformative effect of the camera realigned her original goal into its performative continuation and development.

The ‘chapter house’ of the title is the structure of the work, a framework like the memory theatres of old; in the first half of the performance, a textual score Dimitriou reads backwards at a music lectern with an almost ecclesiastical lilt precedes each selective re-enactment. She shares the stage with video artist David McCormick who is recreating Mark Coniglio’s original role.

A nod from McCormick is the signal for Dimitriou to start; she approaches the lectern where she reads her first score. In silence the two performers approach each other across the stage to perform a ritual cleansing of hands, she with a glass bowl, he with a glass bottle of water and a white towel that he lays carefully on the floor. After the ceremony Dimitriou places the bottle on the floor with the exactness of protocol and returns to the lectern to read the next score. This time she performs the score alone — lying on the floor and rotating her position every ten beats of a metronome until her hand finds the water bottle; she drinks from it for ten beats — while David circles to record her with a tablet-sized camera on the end of a pole.

At this point we do not know what he will do with the recordings; for subsequent scores McCormick moves with the camera as a participant in the choreography but we do not see the images until later when we understand that, like Dimitriou’s textual scores, the captured images serve to transfer past memories into the plane of the present. But they are more than that: in the latter half of the performance the recordings, filtered through a complex algorithmic software (originally designed by Coniglio) that divides them into the five chapters, are simultaneously projected on to five screens — five sheets that Dimitriou and McCormick meticulously unfold and peg to the overhead wires. You can marvel at this magic while you see Dimitriou perform a beautifully slow, languid solo that is qualitatively different from what had come before as if the entire process of recording and playback has changed the intrinsic nature of her dancing. While watching this process of digital creation and re-creation unfold we can also perceive the embodiment of an idea that in the sparse surroundings of serene but minimal gestural movement makes a compelling statement of life’s richness and a reminder that at the source of ideas is the unity of mind and body.

Zoi Dimitriou will perform The Chapter House again at Laban Theatre on April 12, 2016

Posted: December 21st, 2015 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Anna-Lise Marie Hearn, Chantal Guevara, Cloud Dance Festival, Cloud Dance Friends, Daniel Whiley, Elise Nuding, Estella Merlos, Humana Productions, Jacob O'Connell, Jason Mabana, John Ross, Mike Williams, Miranda MacLetten, Yukiko Masui | Comments Off on Cloud Dance Friends

Cloud Dance Friends, New Diorama Theatre, November 29

Miranda MacLetten and Daniel Whiley in John Ross’s Blink (photo: Chris Jackson)

Chantal Guevara’s birthday celebration this year includes, before the chocolate cake, a performance at the New Diorama Theatre by Cloud Dance Festival alumni and friends; it is the kind of event for dancers and choreographers to try out new work in as relaxed an atmosphere as any public performance can be.

Elise Nuding, who opens the evening with a first performance of her I, object, bravely juxtaposes linguistics and wordplay with choreography. She writes, ‘This little nugget emerged during a particularly frustrating period of article writing, as I grappled with the slipperiness of words and their implications.’ The struggle is apparent both in her semantic parsing and in her accumulative gestures. As she arrives at each breakthrough in her argument, Nuding takes off a layer of clothes; by the end she has only got to the level of underwear, which suggests this slippery little battle has not yet reached its logical conclusion. Nevertheless I, object reveals a sophisticated aesthetic at work that, depending on what Nuding does with it, makes this nugget either ‘a small lump of gold’ or ‘a valuable idea or fact.’

I am not sure why Mike Williams titles his work 4’33 after the famous John Cage piece of music and makes it last 8 minutes. Why not call it 8’? Besides, a dance in the spirit of Cage’s 4’33 would have no movement but there is plenty in Williams’ angular, long-limbed plasticity though (at least in this evening’s performance) there is a lack of pliable technique to get the most out of it. Cage’s 4’33 contains a world of ideas — his love of silence, the withdrawal of music from the score, his delight in incidental sounds — but Williams’ dance, for all its movement, lacks this kind of philosophical integrity; he points in the right direction but doesn’t embody what he wants to convey and his final gesture for silence underlies the self-conscious conceit of the whole.

Jason Mabana’s Hidden, a duet for himself and Jacob O’Connell, is driven by a tactile quality, part ferocious, part gentle, that describes ‘the ambiguity of a relationship between two conflicted and dominant people.’ Mabana’s choreography carries its imagery with great strength and poetry like a smooth, rich baritone in a youthful body. There is both a singing quality to Mabana and O’Connell’s movement and a silence in the way they dance that leaves our visual and visceral senses free to enjoy the movement without unwanted punctuation. Hidden achieves what it sets out to do with a purity and sincerity that are refreshing.

Humanah Productions’ Egress starts off with a pile of bodies from which the one underneath slithers out with great difficulty to stand but collapses from its independence and returns to the heap. It is a metaphor of growth and departure in the form of a game, one of many ludic adventures in the work that lead the performers to set out on their own paths without forsaking their social cohesion. The games take the form of a structured improvisation but despite the energy of the performers and the inspired live music Egress never really evolves beyond that initial phase of innocent play.

I saw Anna-Lise Marie Hearn’s Our Physical Intentions at the Kaleidoscopic Arts Platform at the Galvanizers Union pub not long ago where the intimacy of the setting enhanced the intimacy of the thought processes that weave their way through the work and where the intensity of Eleanor Mackinder, in particular, was palpable. It was as if we were watching a conversation between three people in the same room. Even though the stage at the New Diorama is not exactly large, the dancers appear isolated in space. Perhaps there is something else at work: the nature of Our Physical Intentions is an ‘exploration of how our thoughts directly determine and influence our emotions’ but on a seemingly subcutaneous level. The costumes (by Inês Neto dos Santos) resemble the patchwork system of the body’s nervous system and the three performers (Mackinder, Laura Boulter and Lydia Costello) are as much a ‘cognitive pattern’ of thoughts, emotions and reactions as they are flesh and blood. Danced stories have traditionally read from the outside to the inner emotions whereas Hearn turns the process inside out: you follow the process to arrive at a story. In a larger space, however, the internal processes (Mackinder’s intense expression, for example) are less easy to read, distancing them from the story on which they are based.

Yukiko Masui’s Unbox is an ‘investigation into cross-genre movements which aim to be unidentified as a dance genre’ in which she is ‘searching for a place that people cannot put me in a category as a dancer or a person.’ Indeed all we see of her at first is the fingers of one hand playing in a circle of down-light, and when she steps into the light we see a heavily clothed and hooded figure with the physical mien of a young man. She moves in a macho, feline way, mixing contemporary and street dance with androgynous strength and sensitivity though by the time she develops her beautiful, spiral movements the female is in the ascendant. Having expressed so succinctly in dance form the strength and ambiguity of her presence, the conclusion of Unbox appears to contradict the latter part of Masui’s goal: she makes a point of categorizing her identity by letting down her hair and removing layers of clothing. The mystery has evaporated.

In John Ross’s work, Blink — a single chapter previewing a longer work — the symbolic and the expressive are both present in the gestural body. Loosely based on a short novel by Mitch Albom, ‘The five people you meet in heaven’, Blink follows the sensory trail of Eddie (Daniel Whiley) who, having just died and before entering heaven, meets five important people from specific periods in his life. This episode involves his wife (Miranda MacLetten). I have already written about Whiley’s ability — in Sally Marie’s I loved you and I loved you — to plumb the depths of a movement to present us with the clarity of the imperceptible. In Blink Ross works with this ability, exploring the form and substance of a man whose memory is so far detached from the living as to borrow from a spectral world. At one point MacLetten calls his name, which sends a shudder of recognition through Whiley and brings out tears of distant recollection. His body is the material of this dematerialization, a duality Ross expresses in and out of light, seen and not seen. The intriguing power of Blink is the way Ross brings together these contradictions to make visible a relationship that MacLetten remembers all too well but Whiley only senses through his faltering gestures: his nose nuzzling her shoulder, his dancing with her on her toes as if he has no weight or motion of his own or in his tremulous singing an old, shared song. Ross is adept at creating these kind of in-between experiences, between life and death, between remembrance and loss with a subtlety and sensitivity that both MacLetten and Whiley embody so convincingly and that composer Greg Haines nurtures with a haunting, other-worldly solo piano score. Blink may be a fragment, but it contains the promise of something substantial.

I can’t help sensing Estela Merlos is slaying some of her demons in her solo, UKOK, so fiercely provocative is it. Merlos has a lot of fire in the flash of her eyes but there is also a poetic flow in the powerful dislocation of space her movement provokes. While she writes that the work is ‘inspired by the alliance of women with nature in nomadic culture’, Merlos clearly identifies viscerally with the ‘intuition and vigilance of the feminine figure’: she transforms it into a force that surges through her body to the extremities of her splayed fingers and stamping feet with total conviction. It is a fitting conclusion to an evening that celebrates Chantal Guevara’s love of and determination to promote the rich seam of independent dance.

Posted: December 4th, 2015 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Chelsea Theatre, Chris Langton, Dinah Mullen, Jordan Lennie, Joseph Mercier, Laura Dannequin, PanicLab, Rachel Good, Sacred, Sam Halmarack, Swan Lake II: Dark Waters, Sylvia Rimat, Tanya Steinhauser, Ziggy Jacobs-Wyburn | Comments Off on Swan Lake II: Dark Waters & This Moment Now

Paniclab, Swan Lake II: Dark Waters & Sylvia Rimat, This Moment Now, Chelsea Theatre, November 25

Jordan Lennie on his island of feathers in Swan Lake II: Dark Waters (photo: Nicola Canavan)

This is a Swan Lake that is perhaps closer to the Imperial Russian court and Siegfried’s hunting party than you might think but admittedly miles from the choreography of Petipa and Ivanov. When you hear Tchaikovsky’s overture you might be forgiven for thinking director Joseph Mercier is taking cheap shots at a classic ballet but this is more like a surreal 55-minute preface to Swan Lake: what is happening at home in the nest while Odette fights for her freedom against the demonic control of Von Rothbart in the royal palace. Presumably her mate is unaware of her true identity.

As we enter the auditorium we see an island of white feathers on the stage with its sole occupant, Odette’s cob (Jordan Lennie) lying naked on his feather bed brooding languidly on the eggs while awaiting her return. It is a startling homoerotic opening image that joins a long history of erotic swan associations. Hanging from a rope above him is the body of another swan, the collateral damage, perhaps, of the royal hunting party. The stark beauty of Rachel Good’s set is like the swan itself: elegant on the surface with all the workings hidden underneath. Lennie is a tidy, industrious mate who keeps his feathers pristine and buries his domestic appliances out of sight in the soil beneath the feathers: an electric hob, a frying pan, a spatula, a dressing tent, a mobile phone and an old pair of tights.

One of the characteristics of Joseph Mercier’s work is that he presents performers on stage without any distinction between self and character: in Swan Lake II: Dark Waters Lennie is a swan keeping the nest eggs warm but when he is sexually roused he signals climax by crushing an egg in his hand, when hungry he eats one raw, rustles up an omelette or peels a chocolate egg and eats it while watching the audience watching him. There is no slipping in and out of character for it is all undifferentiated Lennie.

Despite Mercier’s description of the work as an ‘estranged ode’ there are moments when he has his tongue firmly in his cheek — his use of Dusty Springfield singing I just don’t know what to do is one — but there is something deeply creative and satisfying in his imagination and the work provides Lennie with moments of extraordinarily beautiful imagery. There is a brief quote from The Dying Swan, a more extended one from Nijinsky’s Faun in which Lennie finds comfort among the wings of the dead swan (to the Springfield track), but the overpowering image is the naked swan staggering blindfolded on pointe among the feathers of his nest screaming for Odette. Mercier might well be expressing aspects of his own psyche but I can’t help feeling he is also touching on aspects of Tchaikovsky himself. Swan Lake II: Dark Waters lives up to its name, swimming from one emotion to another — from sensuality to loss, from frailty to strength, from the clarity of laughter to the loneliness of self-reflection — lapping ever closer to the edge of madness. Lennie’s performance shines but this is an inspired team effort: Good’s set, Ziggy Jacobs-Wyburn’s lighting, Dinah Mullen’s sound design, Lennie’s choreography and Mercier’s direction.

Sylvia Rimat with drummer Chris Langton in This Moment Now

Swan Lake II: Dark Waters is part of Chelsea Theatre’s season of contemporary performance, Sacred. It is the kind of programming that challenges and demands an investment of time, which is the subject of Sylvia Rimat’s This Moment Now that opens the evening. Rimat is as caught up in her subject as Mercier is in his but its nature — the elusive concept of time — demands a more analytical if playful approach. Rimat in her delivery is as precise as the metronomes set ticking at the beginning of her performance though these stand no comparison to the notion of atomic time to which she introduces us from outside the theatre via skype at the beginning of the show. She writes that the work is inspired by conversations with three eminent professors but it is her way of research to start with the highbrow and then find lowbrow, ludic ways to express her findings. She expresses time through spoken text, demonstrates it palpably through the beat of drummer Chris Langton and slows down the performance itself by serving tea half way through. We experience vicariously the present moment of a live cockerel on stage (thanks to the skillful stewardship of stage manager Alasair Jones) and watch filmed interviews with the elderly Eileen Ashmore (who also dances up a storm) and the young sisters Lola and Marlina Steinhauser Somers (clearly influenced but not prompted by dramaturg Tanya Steinhauser). Despite the arcane nature of the science Rimat keeps all her explanations within the framework of performance. It is what might be termed performative science: time is the subject but Rimat’s intelligent stagecraft makes it the unassuming star.

Posted: November 25th, 2015 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Festival, Performance | Tags: C-12 Dance Theatre, Co_Motion Dance, Dance I made on my Bathroom Floor, Dialect of War, Duvet Cover, Emerge Festival, Gemma Prangle, Jean-Pierre Nyamangunda, Left, Maëva Berthelot, Neus Gil Cortés, Omar Gordon, Sia Gbamoi, Tamsin Griffiths, Viviana Rocha, What Is Written Dance Company | Comments Off on Emerge Festival, Week 3

Emerge Festival, Week Three, The Space, November 17

Maëva Berthelot and Omar Gordon in Neus Gil Cortés’ Left (photo: Patricio Forrester)

This is the third program of the three-week Emerge Festival curated by C-12 Dance Theatre at the intimate venue, The Space, on the Isle of Dogs. These small-scale festivals, like Cloud Dance Festival and Kaleidoscopic Arts Platform, give opportunities to young choreographers without any hierarchic selection process: it is a raw mixture of work from around the country that is never less than interesting and can include some gems. There has been a lot of discussion recently about the absence of female choreographers, but in the two programs I saw at Emerge, the majority of choreographers are women.

The only exception this evening is Dialect of War by Jean-Pierre Nyamangunda and Viviana Rocha of What Is Written Dance Company who join Sia Gbamoi to make a trio that starts off quite innocuously but grows in menace. Described as ‘the story of a warrior tribe whose lives are brutally disrupted’, the energy of disruption is carried in the choreography but the narrative of violence is carried in the presence of the dancers, most completely in Nyamangunda whose eyes convey both terror and pain. In Don McCullin’s war photographs it is the eyes of both victims and perpetrators that convey the ultimate darkness of the soul; the use of the face as an integral part of choreographic intent is no different.

Gemma Prangle’s Dance I made on my Bathroom Floor is about as far away from Dialect of War as a programmer could manage. Prangle starts behind a shower curtain in silhouette to the sound of running water and when she raises her arms above the curtain for a stylised soap dance the sound of lathering pervades the room. When she reaches outside the curtain for her towel we can see it is not there; it is a moment of expectation, a simple but effective piece of theatre. Prangle conceived the piece when she noticed how much time she spent dancing in her bathroom compared to the studio, but the attraction of such an idea is that she should be unaware of anyone watching. Who dances in their bathroom to an audience? By emerging from the shower (bone dry) and shielding her naked body with her arms, she acknowledges our presence. She then compounds the artifice by apologizing for leaving her towel in the audience and asking for the person sitting on it to throw it down before continuing her ablutions in all propriety. We are now effectively sitting in her bathroom and the inherent humour and absurdity of the idea has been flushed away.

Co_Motion Dance (choreographers Catherine Ibbotson and Amy Lovelock) present a quartet of women in FORCE, a highly energetic battle for power that relies on the strength and spatial precision of the performers. Some of the jumps also rely on split-second lighting cues for that are too demanding for the limited technical resources available and too much of a gimmick for the level of choreographic sophistication. The force of the work comes from the force of the performers: why contrive this brute physicality? Presumably to make it more interesting to watch, but I would argue that the construction and theatrical intent of the work have to be more interesting first.

The title of Tamsin Griffiths’ work, Duvet Cover, appears to follow a similarly domestic theme as Dance I made on my Bathroom Floor, but the duvet in question is a metaphor. It is the place of comfort, ‘an emotional home’ in a work that expresses the volatility of depression and bi-polar disorder. The piece begins with a film clip projected on to a white sheet showing Griffiths climbing into a giant duvet and relishing its warmth and comfort; the fuzziness of the image makes it look like an ultrasound image of a baby in a womb. At the moment the film ends Griffiths pushes from underneath the screen to lie supine on the stage. Her initial movements remain close to herself as she goes through the motions of adjusting drowsily to vertical and following the path of a hand that seems to have an agency of its own to a score that is dreamy if not hallucinatory. Griffiths’ entire body explodes into action as she follows a volatile narrative; there is no ‘why’ in these shifts of mood, these ‘phases of depression’ as they progress in a certain direction and then suddenly change course. Duvet Cover is a work that can be read on two distinct levels: one that doesn’t make sense and one that does. Griffiths is perhaps playing unconsciously on the ‘invisibility’ of depression and how that plays into misunderstanding about the nature of the disease. She controls her performance even when it seems most chaotic: she displays an effortless virtuosity in her ability to throw herself to the limits of her balance and return to equilibrium. Although she takes emotional risks, Griffiths is not challenged sufficiently in Duvet Cover to extend her range. Perhaps it is one of the challenges of working alone but one of the rewards is to see that raw honesty in a dynamic physical form.

The most complete work of the evening is Neus Gil Cortés’ Left, a duet for Maëva Berthelot and Omar Gordon (Cortés shares the role with Berthelot on subsequent evenings). It has a simple starting point: ‘When we are alone, all we have left is our thoughts…’ ‘All’ is the operative word, for in this fifteen-minute duet there is a great deal to inhabit our imagination and Cortés leaves open that vital gap between choreographic intent and audience reaction. Gordon, who has the dark lines of a character in an El Greco painting, is the manifestation of a relentless, demonic aspect of Berthelot’s psyche. Despite herself, Berthelot circles around him like a moth around a candle and when he finally dissolves into the darkness she is left eerily reliving his gestures. They are two but they are not two, and their partnership is mesmerisingly intense. As a choreographer, Cortés handles the frailty and domination with a freedom and depth of detail that anchor the work in a youthful maturity. She also proves her intuition as director in creating an enveloping sound score around the music of Philip Samartzis and Mica Levi, costumes that enhance the narrative and in managing to create magic from the available lighting resources.