Ian Abbott: Nott A Fierce Umbrella, A Tale of Three Festivals

Posted: October 30th, 2019 | Author: Ian Abbott | Filed under: Festival, Performance | Tags: Aaron Wright, Alexandra Bachzetsis, Alexandrina Hemsley, Andrew Tay, Bernard Martin, Boy Blue, Charlie Morgan Jones, Dance Umbrella, Eirini Kartsaki, Emma Gladstone, Emma Houston, Fierce, Gillie Kleiman, Gisèle Vienne, Heidi Rustgaard, Hervé Jabveneau, Jennifer Lacey, Joe Moran, Julie Chapallaz, Léo Piccirelli, Marco Berrettini, Maribé - sors de ce corps, Marie Béland, Marie-Caroline Hominal, Matthias Sperling, Melk Prod./ Marco Berrettini, Mickaël Henrotay-Delaunay, Nottdance Festival, Oona Doherty, Paul Hughes, Paul Russ, Peter Rehberg, Philippe Chosson, Philippe Saire, Rachel Harris, Samuel Pajand, Stephen Thomson, Sylvain Lafortune, Victor Roy, Yann Marussich | Comments Off on Ian Abbott: Nott A Fierce Umbrella, A Tale of Three FestivalsIan Abbott: Nott A Fierce Umbrella, A Tale Of Three Festivals, October 2019

The choreographic density of October and November is the result of a number of UK dance festivals vying for the eyes and attentions of audiences and artists; over a period of six weeks there’s Dance Umbrella, Nottdance, Fierce, Dance International Glasgow, Shout, LEAP and Cardiff Dance Festival. I spent some time in three of the English ones — Dance Umbrella, Nott Dance and Fierce — to look at their programmes and the sense of community around them.

There are some macro questions around who festivals are for, and what difference they make to the form and to their community. Are festivals moments of cultural change? Do they mark a shifting of taste and aesthetic? Are they miniature economic impact machines? Gentrification tools? Festivals that are simply made up of dance performances? A chance for artistic directors to display their air miles and intellectual baubles? Not all festivals are perhaps clear in what/who/why they are. I’m interested in festivals as a site of repetition as people return to the same city, see the same people, enter the same venues year after year but see different works by different artists. I recognise this is a partial view — in as much as the time I spent at each event was limited — but remembering previous editions of each festival I thought it would be worth looking at the three as a whole. With the shift of focus of the UK Dance Showcase (the new incarnation of British Dance Edition) to actively not invite international promoters to the event in May 2019 and focus purely on UK promoters, Dance Umbrella and Nottdance have worked together to create the October Collection, a project that invited a number of international promoters to spend five days traversing the festivals in Nottingham and London offering exposure to a selected group of artists pitching and presenting work. It is worth noting that of the ten works I saw at the festivals none were created by disabled artists.

Nottdance is a biennial festival in Nottingham that is curated by the team at Dance4. They ‘position the voice of artists at the heart of the development of the festival’. For the 2019 edition they published a three page curational statement on the vision for the festival, co-curated by Dance4’s artistic director/CEO Paul Russ and Matthias Sperling, and announced an ambition that Sperling select his successor for the 2021 edition. I spent Saturday October 12 in Nottingham attending five events — three performances and two discussions; all performance works were from artists based in Canada and/or France and the discussions were led by dance artists based in England.

Extended Hermeneutics by Jennifer Lacey ‘uses the sprawling meta-expanse of Bauhaus Imaginista as a divining system where individual readings are offered to those who desire them’. It is nestled in a corner of Nottingham Contemporary where Lacey and I sit facing each other at a small table. This 30-minute 1-to-1 encounter authored by Lacey leans towards a choreographic divination using the Bauhaus exhibition as a frame and set of tools to interpret the problem you have brought to her. Lacey is hyper attentive, responding to visual gestures and titbits of information derived from the verbal and non-verbal signals that leak from my body; after I choose from four decks of cards, she offers an approach to help me find an answer. Lacey is engaging in an American psychotherapist way; she holds eye contact, keeps the beats in between the conversation natural to a point of believeability. It’s an attempt at seduction, looking into the mirror she is presenting and asking me to find my own answer. It feels akin to an intellectual seaside/end-of-the-pier tarot entertainment and ends with a two-minute 55 second, mainly floor-based solo that Lacey performs for me before our time is up. When I’m taking the time to process the information she’s offering in relation to the history of 1970s Leeds Polytechnic Bauhaus practice or geometric costumes I don’t really pay attention because there is little time for me or the thoughts it conjures up in the moment; it is a broadcast that at that moment doesn’t feel personal at all. A seduction takes time and although the encounter could have been useful, it depends on how much weight you give to fortune tellers and tarot practices — they are all a mirror through which we attempt to see ourselves more clearly.

Beside by Maribé – sors de ce corps at Lakeside Arts Centre is choreographed by Marie Béland who begins with a two-minute introduction that explains that everything the performers say is what they hear on the radio on their headphones in that moment and, parallel to this, their movement score is derived and harvested from the gestures and choreographic body patterns on talk shows, political broadcasts and current affairs TV shows. We get the set up instantly; a performer delivers the words they hear (on this occasion at 5pm on a Saturday afternoon in Nottingham) over the course of 60 minutes, including the recent upturn of form at Notts County Football Club, a programme on Blockchain and Libra (Facebook’s new cryptocurrency) and the Irish backstop, all matched with pre-existing gestures. What is created is an ever evolving, live choreographic meme which reflects some of our broadcast media, music, songs and political broadcasts.

What Béland has created is a frame that could enable this work to last forever; the work will always be relevant because it derives its currency from the radio content broadcast on that day in that city, and it will always connect and reflect the energies and priorities of that day. It could scale up from the three dancers to 13 or 103, depending on the size of the stage or the complexity of the audio narratives. It is funny, because life is funny when it is removed from its original frame. Hearing the absurdity of in-depth analysis of a football game coming from an alien mouth set to artificial gestures emphasises the assumptions of language (word and body) each community uses. The agility of thought and how each performer combines it with straight-faced and physical control demonstrates that Rachel Harris, Sylvain Lafortune, and Bernard Martin are skilled performers, but we see little of their dancing ability; it is more a controlled suite of bodily movement.

How does the relationship of our geographical context to the work we see affect how we see it? The Nott Dance closing performance at Backlit Gallery is the same as Fierce’s Sunday lunchtime performance at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery a week later: Make Banana Cry by Andrew Tay and Stephen Thomson. It’s the difference between a festival closer at 9pm on a Saturday night and a Sunday luncher at 12.30pm; energies, attentions and expectations of experience are entirely different. Described in Nottingham as ‘a continuous barrage of identity politics, a durational parade which contemplates the problematics of universal “Western” pop culture while drawing on the artistic background of each of the invited artists’, it becomes in Birmingham a work that ‘confronts western perceptions of the ‘Asian Fantasy’ in a durational parade drawing on the background of the diverse cast of Canadian artists.’

Set in a catwalk fashion seat configuration with a U-shaped runway on which the performers walk up and down, we see a slow, iterative introduction of each ‘model’ who is over-clothed with up to a dozen layers of items, props and accessories, some of which we would recognise as clothes, some not (tablecloths, giant fans, suitcases). Over the course of 70 minutes, garments and items are removed and embellished leading to a sense of a live GIF parade; each model demands attention for 5 seconds — in one case by swatting their naked butt cheek with a fly swatter — whilst the next comes along with a plunger that is being repurposed as a rocket launcher. The continual attempt of each act to outdo and one-up the next is predictable and is accompanied by a playlist of Asian stereotype music like Mr Roboto by Styx, We Are Siamese by Peggy Lee (from 1955’s Lady & The Tramp) or excerpts from the Miss Saigon soundtrack.

The noon encounter with Make Banana Cry sees a community, audience and staff feeling the effects of Fierce Party the night before with at least forty empty chairs, compared to the neatly organised, manicured, sold-out presentation in Nottingham. Although the prop and costume game is stronger in Birmingham (insert electrical fans, fire extinguishers and 3 phase extension leads) the cool, air-conditioned colonialism of BMAG drags it down. When you see a work again so quickly, you notice differences that were missed before because so much of our audience attention is taken with that immediate first impression. This time I pay attention to prop usage, gait and micro performativity, all of which had a depth of attention and detail that you don’t get from a single viewing. Make Banana Cry is a barrage of bodies, props, and music that raises a wry smile as it attempts to question Asian stereotypes and to examine the transmission of cultural identity, but the form of presentation and the predictability that ensues (and its finale of nakedness) dampens the impact and makes it appear quite facile when in fact there are layers, signs and Easter eggs to discover in multiple viewings.

Fierce is the Birmingham biennial which frames itself as Performance Parties Politics Pop. With his written introduction in the programme, artistic director Aaron Wright goes some way to answering my initial questions about what a festival is and who it’s for. ‘With a world in crisis what use is an arts festival, really? What can art achieve in the context of creeping fascism, mass anxiety and the ever-looming threat of the extinction of the human race? Will the performances get an anti-austerity government into Downing Street? Seems unlikely. Will they convince BP to move their focus to renewable energy? No. Will they bring about the demise of neo liberalism and the White supremacist patriarchy? Not any time soon.’ Instead Wright thinks the festival programme ‘can be boiled down to four elements that feel more vital than ever; communion, empathy, resistance and joy.’

Following on from Make Banana Cry I spend the rest of Sunday October 20 at Fierce encountering another set of performances by non UK-based artists, including Bain Brisé by Yann Marussich, Private: wear a mask when you talk to me by Alexandra Bachzetsis and iFeel2 by Melk Prod./Marco Berrettini; these three artists, all hailing from Switzerland, are supported by Pro Helvetia.

Bain Brisé self describes as ‘A bath is filled with broken glass. A man’s forearm is visible on the surface of the sharp and crystalline magma. The man is stuck inside his bath of glass shards and cannot get out without getting injured…It is impossible for the audience to truly grasp that he is steeped inside some 600kg of solid matter, and that time is ticking by.’ Over the course of 50 minutes in Midlands Arts Centre’s Second Floor Gallery, we see a forearm delicately choreograph itself to slowly evict hundreds of shards of glass that splinter and smash as they hit the floor, scattering glass over the legs of the front row of a hushed audience. It is an act of choreographic removal, a slow unveiling of Marussich’s naked body which is encased in a cast iron roll-top bath filled to the brim with glass. With a live percussion and tense electronic score from Julie Semoroz and a sense of classic 80s Performance Art Top Trumps, there seems to be genuine peril that Marussich’s body could a) be cut to ribbons and b) suffocate under the weight of over half a ton of glass. There is both tension and boredom in play as the accompanying glass drops sting the ears alongside the predictability of outcome as his body finally emerges and leaves the gallery. From a choreographic point of view, the control and stillness of an almost Kerplunk choice of which glass to remove to minimise bloodletting is incredibly watchable and draws the focus into an area of about 70cm x 70cm. As part of his head, second arm and torso emerge, he attempts to pull/lift himself up in the bath to an almost sitting position and the sound of glass shifting underneath his legs and bum is an absolute eyelid twitcher. With the bath’s opacity obscuring the detail of how his tendons are being nibbled by glass, the imagination just runs wild.

Private: Wear a mask when you talk to me, also at Midlands Arts Centre, self describes as ‘a timeless hymn to transitions. A notation of its inner development, but also a mourning sketch for possibilities that were once open but can no longer be realized. In the end, this dance is not about normative gender performativity, but rather about the somatic energy that allows us to introduce moments of what Jacques Derrida called “improvisatory anarchy” in order to interrupt history and trigger cultural change and political transformation.’ Private… is a 50-minute solo conceived, choreographed and performed by Bachzetsis that is the perfect embodiment of Fierce’s 4 P’s. With a presentation, demolition and (re)presentation of gendered movement from Michael Jackson’s choreography to Beat It, to mutated westernised yoga positions as well as football and porn poses, Bachzetsis stares straight down our lens and with inverted alacrity bathes in her own power, including presenting herself in a black latex dress and demanding an audience member to spray shine her to reflective mirrordom. There is silence, space and buckets of technical dance ability in the work — when Bachzetsis wants it on display. Private…is a #findom, #subdom and #choreodom; after all, we are only here to see Bachzetsis.

The festival closer at DanceXchange is iFeel2, a 70-minute work for three performers which self describes as ‘a young woman and a middle-aged man, half naked in a tropical dream world boasting floating plants. They are being watched. An erotic female voice sings strange associations with nature. The elegant trance they trace out is done so according to a minimalist and repetitive structure based on the residue of social dances, which are then mirrored.’ iFeel2 is the embodiment of middle-aged white male confidence and entitlement; as Berrettini and Marie-Caroline Hominal, mirrored in only black trousers and black shoes, deliver a simple, repetitive, six step Tina Turner grape vine to each other whilst holding eye contact, Berrettini constantly crosses the invisible line (without touching) and invades the space, pigeon-heading and gesturing in the pursuit of desire. I cannot help but see Berrettini’s facial resemblance to Harvey Weinstein and this consistent invasion and act of violence on an unflinching Hominal is uncomfortable. iFeel2 is a work that was created in 2012, before the #MeToo campaign and Eirini Kartsaki wrote about the work in 2015 in an article entitled Circular Paths of Pleasure which offers an eloquent analysis of the work and its proximity to desire, repetition and philosophy. However, even with all my favourite components in play — repetitive choreographic structures, unusual scenography and lighting design (by Victor Roy) and an alternative pop soundtrack from Summer Music (a pop band formed by Berrettini and performer Samuel Pajand) — it is a work that in its conception and original creation time was an ode to catharsis, desire and unfulfillment, but in 2019 reads as invasion, violence and trauma. The world has shifted but the work has not.

Moving away from the Midlands, I had three trips to London’s Dance Umbrella to see four works; the three-week programme doesn’t offer the same possibilities of seeing a density of work in a single day. The first was the festival opener CROWD by Gisèle Vienne on the main stage at Sadler’s Wells. CROWD is the ultimate commitment to a concept as Vienne takes a single idea and has the courage to not sway or bend from it. On the soil- and litter-encrusted stage we have 15 White bodies engaged in a glacial movement score that looks like the morning after a loose and faux hedonistic night of drink, drugs and carnal encounters at a Glastonbury type festival; bodies emote, flirt, abuse, attack and re-evaluate each other across 85 minutes to an EDM and trance soundtrack compiled by Peter Rehberg. If this were a political and knowing portrait of the ‘festival community’ where rich, White millennials go for a weekend and pay to get high then Vienne has absolutely nailed it. However, CROWD is described as ‘dissecting the vast spectrum of our fantasies, emotions, and dark sides, in addition to our inherent need for violence and our sensuality. Flying in the face of the different artistic disciplines, the journey Vienne takes us on renders the onstage experience a cathartic one.’ What is it with White, European, middle-aged choreographers and their desire for White catharsis? As a festival opener and a lens to see the rest of the festival through it, CROWD is one that reeks of privilege, Whiteness and a concept that is radically dated. The slow-motion aftermath/energy of party/disco/club has been conceptually rinsed by GCSE dance students for the past 25 years and Vienne adds nothing to the dialogue. We see the anatomically perfect dancers dressed dubiously (working class holiday, anyone?) and present exaggerated limb emphasis and facial gurns with the odd break-out for 30-60 seconds as a solo takes place in real time. With the soundtrack playing in real time (and not slowed down), there is a jarring to our auditory and visual food which doesn’t resolve; it is merely presented without comment. No one really likes to watch other people have a good time, especially when you’re asking contemporary and classically-trained dancers to punctuate and dime stop movements to attempt an emphasis they don’t have the ability to execute. Put this concept in the body of Hip Hop dancers and at least you’ll have bodies that can execute what is being asked of them.

Moving across London to Southbank Centre’s Queen Elizabeth Hall, Hard to be Soft – A Belfast Prayer by Oona Dohetry is the second work from the Belfast-based choreographer and performer, which follows on from the incredible solo Hope Hunt and The Ascension into Lazarus in both the chronology of when it was made but also in the thematic sensibility of a portrait of a city and its people. All life is here. Some life is here. How can you stage a portrait of some parts of a city (Belfast), some of its history and some of its inhabitants? At a sliver under 50 minutes, Hard to be Soft…presents a work in four parts, bookended by solo’s from Doherty with an addition of a dozen young female dancers from the Croydon Sugar Army (Doherty draws a community cast from each tour location to perform this section) alongside a duet from John Scott and Sam Finnegan. It also sees Doherty shift from the small-scale intimacy of the type of theatres to which Hope Hunt toured to the larger and more physically distancing stages of QEH. Scott and Finnegan embark on a topless, fleshy, meaty sumo embrace which is all arms clutching and chest sweating that is the distillation of Doherty’s choreographic signature, tender violence. The Sugar Army with ponytails a-bouncin’ offer V formations, commercial routines to David Holmes score and are the choreographic embodiment of teeth sucking. What made Hope Hunt so electric was the performance and power of Doherty, not her choreographic work on other bodies; this is where Hard to be Soft is lacking. How can Doherty paint herself onto other bodies? That level of ferocity doesn’t translate and so everything around her is viewed as inferior and I’m left thinking about the long shadow cast by Hope Hunt and whether Doherty will be able to escape it. It is also worth noting that this is the first work I am seeing at the three festivals that is presented by a UK-based artist.

There’s something about festivals as agents of gentrification and culture washers when they present the commodified trauma of others for the price of a ticket. Are Dance Umbrella and the other festivals really opening a dialogue and offering an insight into things that are unfamiliar to us like the tension and violence set deep amongst the people and architecture of Belfast that Doherty speaks of or are they perpetuating and cementing the evidence from the Warwick Commission report that arts audiences make up 8% of the population who are the richest, most educated and least diverse.

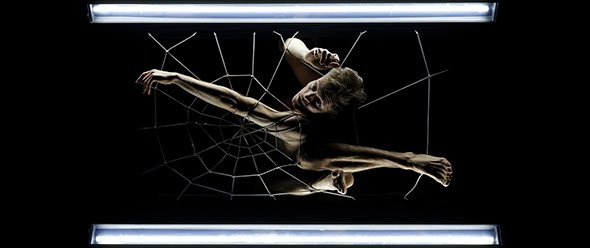

One of the successes of Dance Umbrella is the multi-venue orbital tour of European work for families and young people that has enabled work by Dadodans, Erik Kaiel and now Philippe Saire’s Hocus Pocus to tour to five or six venues across London (I saw it at The Place). Hocus Pocus ‘is based on the power of images, their magic and the sensations they provoke, and it is delicious; it’s a duet that nibbles at the edges of illusion and performance. Parts of Philippe Chosson and Mickaël Henrotay-Delaunay appear and disappear between two strip lights as they emerge and are absorbed back into the darkness. Playing with perspective, birds eye view, and vanishing points, it’s like they’re walking on alternate planes; sometimes we view them from above, sometimes they swing around, sometimes they present isolated limbs on rotation which plays havoc with the eyes as it takes a while to understand how the Jenga body parts are working together. At 50 minutes, the scenography, design and prop-making skill (Stage Device Realisation from Léo Piccirelli and Props and Accessories by Julie Chapallaz and Hervé Jabveneau) mixed with the physical skills of the two performers leave us jawdropped at how the things are happening.

REDD by Boy Blue (who’ve removed the word Entertainment from their name and descriptors in the programme) was the closing show from the Dance Umbrella Takeover of Fairfield Hall — two days of dance, performance, live music, participation and free events in Croydon which included a new commission from The Urban Playground Team and the premiere of Here and Now by Mythili Prakash — and my final show of DU19. Instead of a programme synopsis, Boy Blue offers 143 Words On Grief by R. Moulden as a contextual explainer in the programme.

At 75 minutes without interval, this is a solo for choreographer and co-artistic director Kenrick ‘H20’ Sandy, MBE, supported by a chorus of eight dancers who act as his physical echoes, partial tormentors and skulk about in the shadows of grief. As the first dance show on the newly refurbished Fairfield Halls stage, REDD had an anticipation as it is the follow-up to their internationally acclaimed Blak White Gray. Silences and the mis-expectations of grief trigger different emotions in all those who encounter it, so how are we to comment on the sincerity or portrayal of the grief of another?

As someone who has recently lost a parent, there’s little in REDD that speaks to me on an emotional plane; there are no dramaturgical invitations, no communion of power, and an empathy void; I am left to bear witness and engage if I want. With this lack of generosity, my focus and reflections switch to looking at it as a work of Hip Hop theatre in an attempt to find other things in it but I’m left weary by yet another commodification of trauma.

Sandy, who is on stage throughout, wades, dives, stills and re-enacts some of Moulden’s words — ‘slinks in like a beaten dog and makes its home at your feet…with cracked voice and lolling tongue…reaching into your mouth’ — whilst the shadows of grief make visual noise in the periphery. With a new score from composer and Boy Blue co-artistic director Michael ‘Mikey J’ Asante and a lighting design from Charlie Morgan Jones there is little subtlety and craft in how the lighting, score and choreography come together. Each of the component parts (louder music and a flash flicker of light) often emphasise a particular choreographic move on Sandy all at the same time like three anguish anvils being rammed down your throat.

In previous Boy Blue works, Sandy is usually choreographically en pointe, he pops harder, isolates more cleanly and punctuates more sharply. However in REDD he is the weakest performer. He looked laboured getting in and out of the floor (with his hands on his thigh to help him up), he is out of breath in the final joint choreographic sequences and his performance presence is considerably duller than previous iterations; in the final duet he is unintentionally upstaged by the execution and presence of Emma Houston with whom he dances. It’s like seeing Superman bleed. REDD isn’t ready to be on stage, it doesn’t feel like it is sure what it wants to be (a solo or group work) and consequently what its strongest cast should be.

There are dozens of very average contemporary dance performances happening in theatres every week; that’s because there are hundreds of artists making work across the UK and not everything can be incredible or abysmal; 90% of work sits in this middle ground. However, when a Hip Hop theatre company (who are considerably rarer and we’re talking in the low dozens of artists) makes an average work multiplied by the reputation, financial security and profile of Boy Blue, it feels shocking, but it shouldn’t. Not everything that everybody does will always be the best. We should be able to talk about and write about very average Hip Hop Theatre like we do contemporary dance; as a form, Hip Hop theatre needs honesty in the debate and honesty in the community about work that will enable it to grow and flourish.

One of the strands of Nottdance (alongside performance, studio sharings, etc.) is a discourse strand and during Dr Gillie Kleiman’s session she speaks about her own practice in relationship to Community Dance and cites the idea of ‘Measuring The Distance’ taken from the theatre scholar Shannon Jackson. If we were to measure our practice/distance from a fixed centre (e.g. dance as centre, theatre as centre, visual art as centre) how far or close are we from it? What does this do to centre(s) and who determines what the centre (or perception of centre) is? Do Nottdance, Fierce and Dance Umbrella represent a centre of dance? How might artists and audiences measure their distance from these festivals and what is the proximity and size of their community? Later in the day there’s a panel, Artist. Curator. Leader, conceived by Joe Moran (as part of a larger piece of research he is undertaking) who invited Alexandrina Hemsley and Heidi Rustgaard to be part of it. One of the interesting things that comes up when the discussion opens is that Paul Hughes (who presented at Nottdance earlier in the festival) had asked Paul Russ if Dance4 would do an end-of-the-week sharing on Friday afternoon so that artists could see what Dance4 as an organisation had been working on that week. It is the reverse of when artists, in exchange for using a studio in their building, nine times out of ten give a presentation of ‘work’ to internal staff at the end of the week who then offer their ‘feedback’ on how to make it better. Can you imagine if Dance Umbrella, Fierce, Dance4 and dance development organisations and theatres were to give Friday afternoon sharings to rooms of artists and audiences who would be able to offer an assessment and critique of how they’re doing and how might they do better? Such events could alter the power imbalance that exists between artist and organisations, change centres, and equalise relationships across the entire ecology.