Resolution 2020: WonderWoman Collective, Harry Parr & Autin Dance Theatre

Posted: March 27th, 2020 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Festival, Performance | Tags: Adélie Lavail, Corrie McKenzie, Greta Gauhe, Hannah Adams, Harry Parr, Joe Henderson, Johnny Autin, Marta Stepien, WonderWoman Collective, Zak Macro | Comments Off on Resolution 2020: WonderWoman Collective, Harry Parr & Autin Dance TheatreResolution 2020, WonderWoman Collective, Harry Parr, Autin Dance Theatre, February 20

WonderWoman Collective is a trio of dancers from the London Contemporary Dance School’s Developing Artistic Practice programme: choreographer Hannah Adams and her collaborators Greta Gauhe and Marta Stepien. Their work, Her Agency, explores ‘womanhood and female empowerment’. The program note is written in the style of an abstract, detailing what we can expect to see. ‘The performance will highlight the importance of mutual support in the time of social isolation’…and ‘(the three women) will find themselves in unexpected complex situations, easing into unforeseen connections that demand instant response.’ In the field of academic research papers, an abstract is intended to connect to the arguments elaborated in the text, but in a visual, image-based art like dance such a desired concision is lost between the performance and the onlooker. As Roland Barthes argued in the field of literary studies, once a book is published, its author has no authority in its interpretation. It’s not just a question of the program notes; Adams has interpreted the physical aspects of Her Agency quite literally while loosening their connection to the dimension of dance. On a bare stage with three hanging microphones, we can see the development of ideas like mutual support and precarious balance, as well as complex, unconventional interaction, but a section of guided contact improvisation with Adams at the microphone seems straight out of the school curriculum. What is missing is an enveloping choreographic and spatial dynamic that takes thinking-as-dance to the realm of dance-as-thinking.

Harry Parr’s desire to ‘connect the space, the dancers and the audience with a rousing energy in a shared experience of flow’ is like an adrenalin shot that kicks the evening’s program into gear. PEAK is an unapologetic opportunity for Parr to exercise his ‘own idiosyncratic vocabulary’ in a work that does a lot more; it imprints itself on the imagination by the nature of its formal and spatial organisation. The responsibility lies both with the dancers — Parr, Adélie Lavail and Corrie McKenzie — and with Zak Macro’s lighting that treats light and shade as if it were pulling focus between sharpness and blur. Parr’s idiosyncratic, edgy vocabulary borrows from the gestural language of mime; the use of his body, hands and fingers has a dramatic intent that, although abstract, has a quality of language that gives structure to his choreography. He projects the persona of a puppet master or magician in relation to Lavail and McKenzie who in turn enter into this alchemy with finely attuned contributions that are like a wild, animalistic chorus. Far from simply an exercise in idiosyncratic vocabulary, PEAK has perhaps inadvertently stumbled on an expression of movement in space that is at the heart of drama. Macro’s play of light and Parr’s detached groupings — like the closeup focus on a dialogue of legs between Lavail and McKenzie while Parr’s torso coordinates in the shade behind — work together to create a unified emotional field.

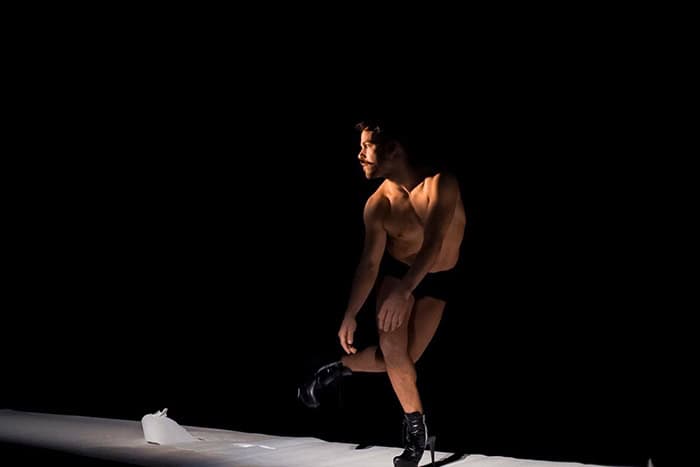

For the purposes of full disclosure, I rehearsed and performed with Johnny Autin in a production of Lindsey Butcher and Darshan Singh Bhuller’s Rites of War in 2014, so I am familiar with his vocabulary and way of moving. But nothing prepared me for the searing psychological evocation of mental health that permeates his solo, Square One, for Autin Dance Theatre, a work that would be impossible to achieve without him having personally driven through the landscape it explores. It is a landscape of black floor and walls in which a broad cylinder of white paper in various permutations is both the material of his preoccupation and his path to survival. Autin is already on stage as we enter the auditorium, obsessively tearing white paper into small squares and littering the floor around him while staring out absentmindedly at the audience as if through a window. The crossover between mimicry and the recollection of mental disturbance is unnerving but the visceral energy of Square One derives from this proximity of performer and subject and Autin has both the courage and necessary distance to combine the two. The effect is a carefully constructed diary of images that is both attractive through Autin’s sensual athleticism and chastening in its psychological fragility. Joe Henderson’s lighting enhances the idea of archetypical opposites, contrasting the white paper against the black walls to create opacity and translucence, shadow and substance.

The program defines Square One as a work in progress, but the performance belies this; it is polished with experience, candour and Autin’s perverse delight in performing it.