Duda Paiva, Blind, The Coronet Theatre

Posted: April 18th, 2023 | Author: Nicholas Minns & Caterina Albano | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Christiano Bortone, Daniel Patijn, Duda Paiva, Itzik Galili, Mark Verhoef, Nancy Black, Wilco Alkema | Comments Off on Duda Paiva, Blind, The Coronet TheatreDuda Paiva, Blind, The Coronet Theatre, March 8, 2023

Next up on The Coronet Theatre’s Spring season after Titans is Duda Paiva’s Blind, a theatrical framework conceived by Paiva and Nancy Black that charts Paiva’s life from a childhood disease that left him temporarily blind in his native Brazil to an inspired maker and manipulator of puppets in the Netherlands. Blind links these two autobiographical events to trace the journey of his ‘surreal path to healing’, but implicit in his performance are some unspecified details in between: having trained as a dancer and actor in Brazil, India and Japan, Paiva settled in The Netherlands where he was invited by choreographer Itzik Galili to be part of a co-production with an Israeli puppet company. The production never happened but Paiva was so intrigued by the puppets that he asked the members of the company to train him in their craft. He didn’t understand why he was so drawn to this form of theatre until one day, holding one of his puppets by its neck, he was immediately reminded of how he had held his brother’s neck to be guided through the streets of his hometown when he was suffering from his eye infections. This haptic experience informs the emotional core of Blind — of finding one’s creative path through adversity — that puts it in the same category as Christiano Bortone’s 2006 film, Rosso come Il Cielo, which follows the story of a young Italian boy, Mirco Mencacci, from the accident that blinds him as a boy to his becoming a prominent sound engineer. Both Blind and Rosso come Il Cielo translate the resilience of the human spirit into an artistic form that embodies and heightens it.

Another effect of Paiva’s disease was a severe blistering of his body. In addition to wearing a large pair of goggles, he arrives on stage in a onesie of conspicuously misshapen bulges on his chest, back and legs, and takes his place next to one of several audience members seated on either side of the stage. Striking up casual conversations as he moves from one to another, he draws each person into his story, telling them how this setting reminds him of the waiting room of a local curandera, or faith healer (known as Madam) to whom his mother first took him to find a cure. Paiva recreates the waiting room, like a theatre within a theatre, by asking his audience what brings them there, or asking for their indulgence in giving his blistered body a scratch.

Wilco Alkema’s music and sound design bring emotional colours to Blind, while Mark Verhoef’s lighting gives it visual intensity. Daniel Patijn’s set is both decorative and enigmatic, having no immediate connection to Paiva’s opening discourse: three upturned bell-jar frames covered in white embroidered material like elaborate crinolines are supported by ropes and pulleys at three corners of the stage. The fourth item is an empty pedestal. Paiva hoists the crinolines into the air one by one, continuing to engage his audience by asking them to hold the ropes until the stage is set and they can let go. In this engaging preamble not only does he gain our full attention and curiosity, but Patijn’s set comes into its own and Paiva has prepared the stage for the appearance of Madam.

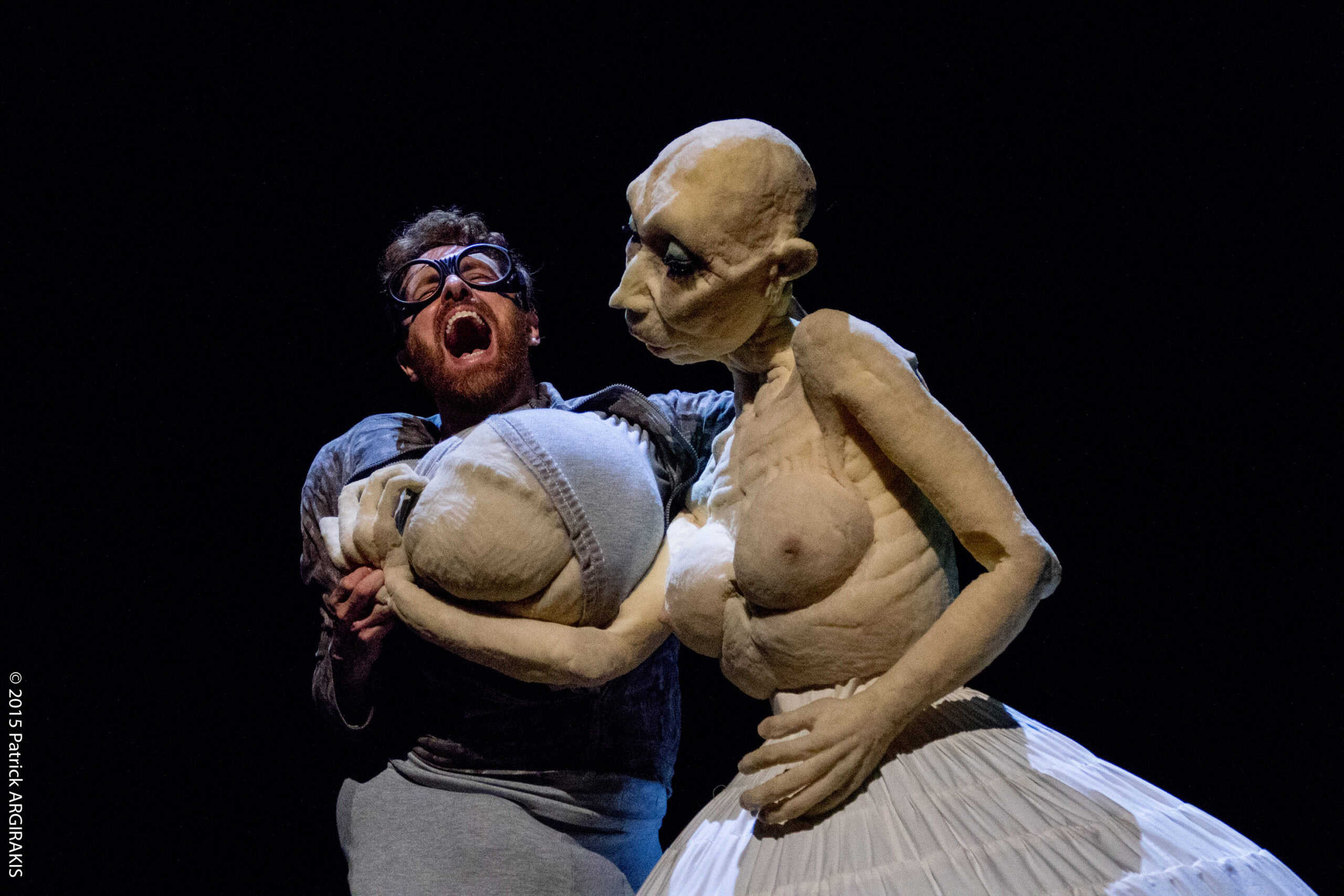

Madam is hidden upside down inside a crinoline, and Paiva, with a magician’s deftness, first reveals her shadow with a torch and then upends the crinoline to reveal her charismatic torso which he places on the empty pedestal. The expressivity Paiva imbues in her soft foam body is remarkable, deriving as much from the dancer as from the puppeteer/ventriloquist. He has Madam wrench a soft, amorphous lump from his chest which he unfurls into another figure that gives his disease a disarmingly humanoid form. Paiva vents his frustration and anger against this being but when he later wrenches the remaining lumps from his body, they too form humanoid figures towards which Paiva expresses as much tenderness as frustration. Blind centres on this ambivalence towards disease, aware that, in Paiva’s case, it is as much an affliction as it is the catalyst of his development.

We all have our physical ailments — visible or invisible, latent or manifest — and our vision may not be as acute as we would like. But if we understand disease as something outside ourselves that somehow interferes with our development, the humility and generosity of Paiva’s artistry in this beautifully constructed and inspired performance leads us to readjust our thinking about adversity. Blind may well be a consummate allegory of healing.