Posted: December 3rd, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aideen Malone, Dan Canham, Elizabeth Taylor, Kate Rigby, Margaret Pikes, Neil Paris, Pavilion Dance, Ronnie Beecham, Sarah Lewis, Smith Dance Theatre | Comments Off on Smith dancetheatre: Agnes & Walter, A Little Love Story

Smith dancetheatre, Agnes and Walter: A Little Love Story, Pavilion Dance, November 8

I had the pleasure of seeing Smith dancetheatre in Neil Paris’ Agnes & Walter: A Little Love Story at Pavilion Dance at the beginning of November. Pavilion Dance has a great venue for smaller-scale dance and a thoughtful, engaging program. The front-end team of Deryck Newland and Ian Abbott nurture their dance and their public in ways that may encourage BBC arts editor, Will Gompertz, to modify his elitist slant on the benefits of arts funding. But back to Agnes & Walter.

I was sure Dan Canham and Sarah Lewis were going to speak in the opening section; language is so close to the surface of their movement that it seemed inevitable it would materialize, but nobody says a word. In that eloquent, perfectly-timed opening sequence Paris introduces the absent-minded, clean cut Walter (Canham) standing at a pale blue table dreamily running a string of Christmas lights through his fingers, checking them without looking. His wife, Agnes (Lewis), in a dress and apron is resignedly sweeping sawdust from the ground around the garden shed (which later doubles as a gingham-curtained house) as if she has done it many, many times before. There is a sense of nostalgia in the costumes (by Kate Rigby) and the set (lit nostalgically by Aideen Malone), a return to what is perceived as a homely set of values and an almost naïve sense of the goodness of life. Walter gets to the end of the string of lights, puts them down and crosses to the shed as Agnes comes over to the table to check the lights for herself (we are not the only ones to think Walter is absent-minded). A few moments later Walter emerges from the shed covered in sawdust, emptying it from his pockets and spreading it at every footstep. Seeing this, Agnes commits hara-kiri in slow motion with a kitchen knife right there on the pale blue table to a melodramatic Hollywood horror score. Walter immediately springs into action as the surgeon in his plastic safety goggles, saving his patient with consummate skill: pulling out the knife, plugging the hole, sedating the patient and stitching her up. He checks her vital signs, has to resort to shock treatment and succeeds in reviving his patient to a sitting position. She falls back but Walter applies his healing hands to her chest; she gestures ‘mouth to mouth’ to the romantic surgeon, so he inflates her by degrees until she reverts to life. She palpitates her heart with a fluttering hand, expresses a certain sadness that the play is over and starts to clean up.

All this makes perfect sense when you know that Agnes & Walter is based on James Thurber’s short story, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. It is an inspired realization, and although it never again approaches its inspiration so purely as in this opening scene, Agnes & Walter confidently develops its own variations with Thurber-like humour. There is the couple of Walter and Agnes in older age, in which it is Agnes (Elizabeth Taylor) to whom her husband’s earlier absentmindedness seems to have migrated. She dances a poignant solo in which she appears to be in a dream, dancing around a maypole, waving at everyone, gathering spirits from the air, pulling them down to her lips as she rises up on tiptoe to meet them. Walter in older age (Ronnie Beecham) is as spry as his wife used to be, maintaining a risk-taking active life, finding pleasure in canoeing on the roof of the shed (as his wife wheels it across the stage) or in performing a rip-roaring dance with a pair of bunny ears around his neck. If this is the golden age, bring it on.

Weaving between the two couples is the figure of their guardian angel or spirit (Margaret Pikes), helping to resolve their problems and lending their narrative an emotional quality that derives from her voice: she does not sing her songs, she lives them, particularly Léo Ferré’s Avec le temps. In fact, music throughout Agnes and Walter – from Tammy Wynette’s Stand By Your Man to Bruce Springsteen to Henryk Gorecki – provides an emotive backbone that reinforces the dance.

Paris’s choreography grows from the ground on which the characters stand, developing from the stillness of a thought into a phrase, just as Walter Mitty’s reveries were sparked from something he saw on his excursion to the shops. With Canham, the thought lingers unhurriedly before the movement develops but Lewis is more spontaneous. Responding to the wind (generated on stage by a 1950s-style standing fan) and to the second movement of Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, she immediately lets down her hair, breathing in deeply, stretching up in ecstasy, her arms dancing up in the air, head raised, smiling, aspiring. She stands on the table to get higher, lets go, and falls to the floor, yet after each collapse, she clambers back to the source of the wind. Feeling the air in her face and hands again, she reaches like a young child pulling spirits from the air (a recurring theme in Agnes & Walter), before the wind finally dies out.

If at first the two Agneses and Walters seem to pass across each other as different couples, towards the end they become superimposed in a quartet of coexisting ages. Canham develops a theme from sweeping the floor into a reverie of uncertain movement; Beecham joins in with his own variation on Canham’s theme. They stumble together, both finishing with arms raised and sitting on the table side by side with their backs to us in touching unity. Pikes, leaning against the shed, sings her final song, Springsteen’s My Father’s House: ‘I awoke and I imagined the hard things that pulled us apart Will never again, sir, tear us from each other’s hearts.’ Taylor and Lewis step pensively on to the stage, step together, step together; Canham and the smiling Beecham gradually join in. Pikes opens the door of the shed and puts up Walter’s Christmas lights in the doorway while Canham and Lewis begin a variation on a theme of making up (this is, after all, a little love story). Lewis lures Canham into the shed, closes the door and turns off all the lights.

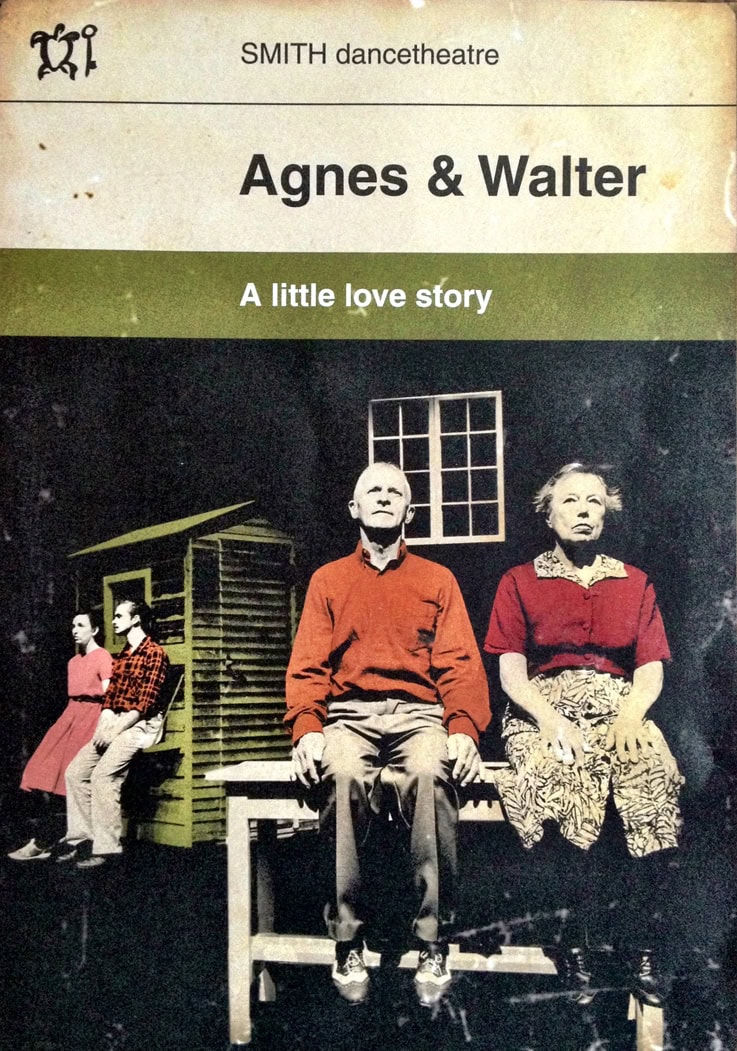

There is something about the image of Agnes and Walter in the publicity material that is immediately appealing. In its colouring and content it contains all the elements of the work: its beguiling charm, its emotional range, its generational range, its down-to-earthness and even its literary provenance. It might have its origins in a bygone age, but the reach of the performance draws inspiration from the air and has room to breathe, making the characters in Agnes and Walter never less than fully alive and fully present.

Posted: November 30th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Adam Carree, Andrew Loretto, Anthony Missen, Company Chameleon, dieb 13, Dieter Kovacic, Fabrice Serafino, Gameshow, Kevin Edward Turner, Mat Johns, Signe Beckmann | Comments Off on Company Chameleon: Gameshow

Company Chameleon: Gameshow, Nuffield Theatre, University of Lancashire, November 1

photo: Brian Slater

I saw Company Chameleon at the 2010 BDE in their first work, Rites, which dealt with the relationship of father to son and attitudes toward manhood and growing up. Two years later the duo of Anthony Missen and Kevin Edward Turner is again dealing with social development but from an external perspective. Gameshow is about the insidious values of advertising and mass media — particularly television. In the program note, Missen and Turner write that ‘since the early part of the 20th century, ad men have been selling the public false dreams, lifestyles to aspire to so that we always want the next thing. In creating Gameshow we wanted to parody this, to look below the surface of the commercial world and interrogate the substance of the lifestyles we are being sold. Alongside this runs the deconstruction of the cult of celebrity, a phenomenon driving aspirational lifestyles to a new level.’ Rites was very much a stage work, but Gameshow belongs as much in the television studio: while maintaining their distinctive form of dance theatre, Missen and Turner have collaborated with video artist Mat Johns to produce advertising and hidden camera clips that ratchet up the scope and efficacy of their work considerably. This is the first script Missen and Turner have written, and they have further broadened their collaborative approach by working with dramaturg Andrew Loretto, set designer Signe Beckmann and composer Dieter Kovacic (aka dieb 13) along with old friends Adam Carree (lighting designer/production manager) and Fabrice Serafino (costume designer).

Gameshow’s narrative follows the fate of a game show host, J.O.Z. (Turner in a blonde wig, white jacket and trousers, red shirt and bare feet), whose brash over-confidence diminishes in direct proportion to the increase in tenacity of a wily contestant (Missen). Turner’s opening number is a tongue wagging, hip-undulating, over-the-top dance that exaggerates — but only just — all the piped sex appeal of a game show host looking to assert his personality over the contestant and audience — especially (in this case) the girls. Turner drums up applause as he leaves the stage and basks in the adulation. Once he has left, Missen in tee shirt and jeans rolls on from behind a desk. Not at all used to the spotlight, his movements suggest discomfort, but he has the fire of someone who wants to make his dream come true. His opening dance includes a section in which he seems to cycle on his side across the floor, suggesting a willingness to advance despite the friction.

Gameshow is pure spoof, but embedded in the narrative is a commentary on the role of television advertising in which parody gives way to satire. In the game show’s first commercial break we see (projected on a screen on the back wall) an ad for Solvaproblemol, a dissolvable tablet for relieving symptoms of stress and anxiety. A white-coated doctor (Turner) talks in a snake-oil-salesman’s way about a new product to counter suicidal tendencies. He approaches a figure seated on a bench, pats his shoulder patronizingly and introduces him as a patient who can testify to the product’s efficacy. Instead the patient puts a gun to his throat and as the camera cuts to Turner’s face, we hear the shot, and see Turner’s face spattered in blood. Without missing a beat, the smiling Turner introduces the product that we see behind him in a field, about the size of a giant tractor wheel, as pristine as an Alka Seltzer.

Back in the studio, J.O.Z. is making his contestant jump through hoops (literally) to demean him in front of the audience, and to make himself look good. J.O.Z. exudes contempt by beating Missen with a plastic kosh, and putting a bucket over his head. Just as the treatment begins to remind us of images from Abu Ghraib, the next commercial for a video game corroborates it: two of the contestants resemble Bin Laden and Bush and another two resemble a hoodie and Raptero Cameron. In the video clip the underdog wins. This signals a turning point in the game.

For the next round, Turner asks one of the girls in the audience to pick out a piece of paper from a hat. The rule of this round is that Missen has to rap to whatever subject is on the paper. The girl draws The Lord’s Prayer. Turner is complacent, Missen is in a panic, but he does it and passes to the next round. Through his earpiece, Turner gets a call from his boss who is angry at his mismanagement of the show, and we understand that unless Turner can cause Missen’s downfall, his job and all that it represents is on the line. As the dejected Turner walks out of the studio, we see a slick clip of him as a macho sex symbol whom no beautiful woman can resist. It is in fact an advertisement for a perfume, Messiah, that J.O.Z. is promoting. Turner’s state of mind in the clip is in stark contrast to his state of mind when he arrives home to his wife, who is…Missen in fetching dressing gown and slippers. She goes to comfort her husband but he is in no mood to be comforted; he makes a weak attempt to show some warmth, but can’t bring himself to follow through. The sequence of this domestic dysfunction — made all the more dysfunctional by Missen’s drag — lasts an uncomfortably long time, but the discomfort is a metaphor for the disconnect between the onscreen image and its reality. Jimmy Savile’s story and the BBC’s reaction to his behavior is a recent example.

Turner makes his way back to the studio dreading the final stages of the game. He arrives like a zombie, but when the lights go up his grimace warps back into a smile; the studio is his world. In this final round, Missen has been given the task of making seven people in the street hug him and say they love him. The filming by hidden cameras is beautifully realized, as we see Missen carrying two shopping bags falling repeatedly on a busy pavement at the foot of a succession of unwary individuals in an attempt to gain their sympathy. He does it brilliantly, and once he has gained their attention, he explains his task and asks them for a hug and for each to say I love you. Some don’t want to know, others don’t have a problem. It’s very touching and very funny. Missen gets his seven people and passes this test. Back in the studio, Turner says to his audience ‘Let’s welcome him back’, but doesn’t mean it. He is determined to block Missen’s success and sits him down to a game of three riddles, like Turandot without the opera house: the third riddle is ‘What does God never see, a King sees only once and you see all the time?’ delivered with due condescension. Missen eventually gets it: an equal.

Turner is finished, washed up. He gets home, takes off his wig and jacket, brings out a large fish platter of powder and sniffs a few lines. In his vengeful imagination he engages Missen in a combative dance, which turns to violence, but Missen starts to beat the ever-smiling Turner at his own game, until he leaves him defeated on the floor in a pool of light needing desperately a dose of Solvaproblemol that he had so cavalierly endorsed.

One of the qualities I remember from Rites is the physical prowess of both Missen and Turner, not only in their individual dance sequences but in the closeness with which they worked together. In Gameshow, dance is used to great effect in the expression of the contrasting characters of host and contestant, but the dance sequences are not as central to moving along the story as the text and film. Both Missen and Turner put in excellent performances in their respective film roles.

The soundtrack by Dieter Kovacic is everything one would expect from a composer who has worked continuously since the late 80s ‘rendering cassette players, vinyl, cds and hard disks into instruments’ and it links each segment of the show effectively and sensitively with both a lovely sense of humour and pathos.

Because the setting of Gameshow straddles both theatre and television, getting the right balance of stage environment is a challenge. Television has slick production values, leaving little to the imagination, while the stage is more ‘handmade’ and leaves much to the imagination. The camera can also screen out unwanted elements in the studio, whereas in the theatre what you see is what you get. What you see in Gameshow is a set designed to accommodate both a television studio and the kitchen table in J.O.Z.’s home, which stretches credibility a little too far. But if the production values of television and theatre have not found a way to coexist seamlessly in Gameshow, the title of Company Chameleon’s new work, Pictures We Make – scheduled to open on February 14 at The Lowry – suggests the research continues.

Posted: November 27th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Adam Towndrow, Alice Gaspari, Alicia Pattyson, Ana Dias, Andrew Willshire, Annie-Lunette Deakin-Foster, C-12 Dance Theatre, Camila Gutierrez, Chris Rook, Cindy Claes, Esther Vivienne, James Williams, Janette Williams, John Ross, Mikkel Svak, Miranda Mac Letten, The Space, Tomoe Uchikubo | Comments Off on C-12 Dance Theatre: Emerge

C-12 Dance Theatre, Emerge, The Space, November 24.

A show full of super heroes, a sofa and some pretty angry women.

There is not a lot of space in The Space on The Isle of Dogs. It occupies what was once St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church, built in 1856 for the Scottish shipyard workers employed on the building of Brunel’s The Great Eastern. The features of the chapel have been maintained, with the stubby ionic columns of the vaulted apse framing the thinly raised stage and the nave continuing the stage at floor level with room for about fifty chairs at one end. There are no wings but the two doors at the back of the stage and the aisle entrance to the auditorium are the principal entrances and exits for the performers. Had those Scottish shipyard workers seen the performance of C-12 Dance Theatre, they might have thought they had died and gone to heaven.

Before the performance begins, Adam Towndrow, artistic producer of C-12 and the initiator of Emerge, welcomes everyone and gives a breakdown of the evening: three works by three choreographers: one by C-12’s artistic director, Annie-Lunnette Deakin-Foster, and two by emerging choreographers James Williams and Miranda Mac Letten. On stage for the first piece, James Williams’ In New Light, are a drum kit played by Williams’ sister Janette and a bass guitar played by Andrew Willshire. The only prop is a medium-sized black sofa, like a soft brick, on the auditorium floor.

Ana Dias and James Williams in In New Light photo: Chantal Guevara

A single drum beat rings out in the dark like a call to arms. As the thunderous beat continues, a very lazy strobe illuminates the sofa and two men (Williams and Willshire) sitting either side of it like guardians in the night. Enter Ana Dias as a glowing apparition down the aisle. She quickly sheds any illusion of a spectre by jumping up on the sofa, her huge shadow projected on to the side wall. She turns towards us with protective arm gestures, standing as if on the prow of a ship while the sofa is turned beneath her. Over the course of In New Light the sofa becomes in effect a third performer that is upended, turned and overturned in counterbalance to the equilibrium of its human occupants. The roots of Williams’ inspiration derive from parkour, or freerunning, but he reduces the limits of his environment to this sofa and the stage. Because the dance involves a man and a woman, there is also an inherent tension in the narrative and it is the combination of the freerunning and the narrative with the physical prowess of the two performers that is intoxicating: two performers sliding into spaces with the speed and precision of acrobats yet with a warmth of feeling that is rooted in the living room rather than the ring. Intensely physical, In New Light is conceived on an intensely personal scale, in which all the creative elements link together into one dynamic, multi-dimensional jigsaw puzzle.

John Ross in The Endeavour to be Super photo: Chantal Guevara

The aerial buzz descends, and the weight of the chapel reasserts itself as we watch the change of scenery for Miranda Mac Letten’s The Endeavour to be Super. Exit drum kit, bass guitar, amps and sofa; enter Marty Stevens’ and Mac Letten’s coat stand, black telephone on a side table and two screens (as in room dividers) with scraps of Batman memorabilia stuck on with childlike enthusiasm. Mac Letten is a C-12 performer (though not in this work) and the founder of her own company, Kerfuffle Dance, of which three of the dancers in the piece are members: John Ross, Camila Gutierrez and Esther Vivienne. The fourth is Chris Rook. Three of them have graduated from London Contemporary Dance School and one (Gutierrez) is in her third year. Together they have a lot of drive and a lot of fun, with the more experienced Rook as rehearsal director for this work, ‘a comical, high-energy performance based on the human psyche’s need to believe in something bigger than oneself.’ It’s a tall order, but the idea is based less on Nietzsche than on Bob Kane’s Batman as translated into the camp 1960’s television series. Not that The Endeavour to be Super is camp; from Ross’s first entrance as Batman at home hesitating to pick up the phone and petulantly flipping his cloak when he misses the call, or Gutierrez as Batgirl trying to recharge her batteries – and her libido – by massaging her nipples, it never intends to be serious. What comes across is a romp of egos and alter egos, dastardly subterfuges (Rook in dastardly good form) and disguises that deliver the comedy and high energy while going light on the bigger picture. Perhaps that is the fault of an over-ambitious program note, but what Mac Letten does develop is the comical gap between our aspirations and our actions. Kane’s Batman developed his aspirations before he donned his disguise; this quartet of masked raiders starts with the disguise and work backwards to discover indecision and confusion, which lead to catfights (Gutierrez and Vivienne pull out all the stops) and a delightful, simulated scrap between Batman and Batgirl in which the inflicted damage is recorded in true comic strip style on cue cards reading (among many others)Bam! Biff! Wham! and Pow! It is all too much for this Batman, whose aspirations are left dazed and confused, but the infectious vitality, fun and bravado of the choreography and of the performers remain.

Miranda Mac Letten in Scorned photo: Chantal Guevara

After the intermission (for which we are ushered outside), we return to find two figures standing on stage enveloped ominously in a white sheet. A row of candles burns in the back of the apse, creating an almost monastic environment (the design sensitively conceived by Tomoe Uchikubo and lit beautifully by Mikkel Svak). Two women dressed in black (Alice Gaspari and Cindy Claes) enter and free the two figures (Miranda Mac Letten and Alicia Pattyson) from their mute captivity and clothe them in long silk dresses. Scorned is an extract from a new work by Annie-Lunnette Deakin-Foster, but if the backstory is unknown the emotion of the work is very quickly apparent. Scorned takes its cue from the phrase ‘hell hath no fury like a woman scorned’ from William Congreve’s Restoration play, The Mourning Bride, and there is indeed a sense of jilted love on the eve of a wedding that threads through the work. It could also very well be a reworking of the mad scene from Giselle choreographed for a quartet of women with very different bodies and different training but united in their emotional response to unseen events, and it is how each one express it — in their eyes, in their gestures, in the way they hurl themselves through space — that draws us inexorably into their suffering and draws the work tightly together. There is something about Claes’ krumping vocabulary that tenses the space around her like an expressionist drawing, and there is in Gaspari’s lyrical, classical line a sculptural quality that expands her space. Mac Letten’s white dress and Pre-Raphaelite look is as icily cold as her madness is raging and Pattyson’s gently quality is rendered vulnerable rather than fearsome by high emotion. Add to the play of qualities the total involvement of the women and Foster-Deakin’s choreography extending the expression dynamically in all directions, it is all the space can do to contain it. There are some beautiful images: the muted sheet is stretched into a symbol of taut emotion, a catapult for Mac Letten and has undertones of a nunnery; crisped hands erasing a stain on the floor, Claes’ hand at her throat fighting for her life: images from the edge of sanity. And then the dawn seems to break and the wildness calmed. Congreve’s play has another famous line: ‘Music has charms to soothe a savage breast’, and this is exactly what Kerry Muzzey’s Where There’s A Will does. Pattyson resolves her doubts and fears, is helped by Gaspari into a white wedding dress and ascends the aisle towards the exit, but Mac Letten’s fury has not yet abated; she cannot bring herself to meet her groom. Claes leaves her in Pre-Raphaelite dishevelment lying on her wedding gown like Ophelia at the edge of a watery grave.

Posted: November 6th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: 50 Acts, Dance Umbrella, Nigel Edwards, Wendy Houstoun | Comments Off on Wendy Houstoun: 50 Acts

Wendy Houston: 50 Acts, Dance Umbrella, Platform Theatre, UAL Central Saint Martins, October 14

Wendy Houstoun in 50 Acts. Photo: Chris Nash

‘This is the beginning. This is Act 1. This is the bit where the lights go down and this is the bit where I turn around and walk to the back.’ Thus begins Wendy Houstoun’s 50 Acts; there is no artifice, just a slight inflection of her voice, but her delivery absorbs all our attention, drawing us inescapably into her world. This is one of the shorter of the fifty acts, some as brief as a stage direction and none longer than a Chopin Prelude. Collectively they contain tightly packed layers of poetry (Houstoun’s own), music clips, recorded interviews, political speeches, telephone messages, psychic consultation, health and safety regulations, and archival film that Houstoun (with lighting designer/production manager, Nigel Edwards) converts through the miracle of transubstantiation into a potent theatrical form exploring two of her bêtes noires: dangerous thinking around the issue of age and idiotic marketing speak.

In As You Like It, Shakespeare wrote ‘All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players: They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages.’ Like Shakespeare, Houstoun uses the stage, and her presence on it, as an analogy for life (‘how dare you take up centre stage when you are clearly middle aged…’) but concentrates her fifty acts on the latter ages (and some other irritations). ‘I am looking for a way to play this part where age doesn’t make any difference.’ She does, convincingly, because she is such a brilliant performer.

Act 2 introduces us to Houstoun’s aphorisms, which appear as scrolling text on the screen behind her – almost too fast to read let alone write down, so I can’t really comment, but based on the quality of Houstoun’s live delivery, these aphorisms deserve more generous treatment. A book, perhaps? Dance Umbrella printed mugs and tee shirts? Ironically all I remember is ‘Time and space died yesterday.’ Act 3 is a triumphant yes yes yes, and Act 4 a defiant no no no. Act 5 is an affirmative yes to the human race and a sardonic yes to the rat race, in which silent film footage of crowds running in the streets haunts Houstoun who dashes about the stage to avoid them to the accompaniment of one of Chopin’s nimble Preludes. In Act 6 she feels her pulse.

Chopin and Shakespeare are both big influences here. In Act 9 Houstoun recites a prologue in Shakespearean rhyming couplets: ‘…advancing time, which lazy thinking calls decline’ with a searing reference to old age as ‘sadfucks past their bloom…clogging up time’s waiting room.’ It also contains the first of many failed magic tricks to make herself disappear (‘the absence there for all to see.’). Like a consummate clown, she can get away with making people laugh at serious issues, even matters of life and death.

It is easy to get caught up in watching Houstoun perform (the content of the piece) and not realise how carefully 50 Acts is constructed (the form). In her program note, Houstoun writes candidly that she has been trying to make this piece for some time. ‘Somehow the form meets the content in a way I have not achieved before (I have to thank Matteo Fargion for that).’ I have seen 50 Acts three times and each time it is slightly different, but this time I would concur with an audience member I overheard: ‘She absolutely nailed it.’ The form of each act — and of the whole — consists of a complex layering of meaning: sound effects, music, projected text and props reinforce Houstoun’s own finely-tuned speech. The advantage is that whereas she can only speak one word or phrase at a time, this vertical layering adds to her expressive palette like a painter applying impasto. Consider the broadcast, in the final acts, of platitudinous politicians defending austerity measures. The speech is overlaid with off-stage screams, the chiming of Big Ben, a spliced parliamentary chorus of Here! Here! and Peggy Lee singing Where or When? while Houstoun sits quietly waiting in the shadows of her final acts. The cumulative effect is such disillusion that it might come with a health warning were it not for Houstoun’s brand of dark humour.

50 Acts takes a break from the question of ageing to let off steam on another topic: ‘The world of questionnaires, idiotic marketing speak and non-stop initiative drivel has been driving us mad for some time so I am happy to get a little of this irritation out of my system.’ Houstoun dons a hard hat and an ANSI Class 2 safety vest, and cries, Heads! while samples of health and safety regulations like Do not carry loose objects scroll down the screen. She is subject to various assassination attempts from gunshots throughout the piece — one of the hazards of the job — and regularly checks her vital signs: putting a microphone to her heart on one occasion we hear a thumping beat; she puts it to her head and we hear an ambulance siren. Houstoun is not beyond making fun of herself to make a comment about our mental well-being.

After the half-time interval, in which we remain in our seats watching Houstoun taking a breather, an alarm like a school bell sounds. Houstoun brings on a music stand with a score, a wooden stool with a pile of vinyl records and a hammer. We hear an interview in which two women are talking about our need to breathe more deeply and to use time as tendrils that we can pull out as a way of foreseeing the future. Houstoun is busy unraveling a cassette tape. There’s a drum roll followed by another Chopin Prelude. Houstoun stands with her eyes on the score, a hammer raised in her right hand and a vinyl record resting on the stool in the other. On an emphatic chord in the music she smashes the record with the hammer and prepares another, hitting the accents in the music (and the records) with perfect timing until the Prelude – and the pile of records – is finished. This is perhaps what she means by ‘getting a little of this irritation out of my system.’ She returns to the cassette tape, feeding its tendrils through her fingers like a medium looking into the future. ‘I’m getting a cross; it’s in the south: a southern cross…I’m getting a pension….no, no, I’m not getting a pension…I’m getting labels, labeled…I’m just getting the odd word now: tainted, cradle, grave, burden, tax…We’re in a dance hall, a palace of wasted steps…We’re doing the dance of the daft, the half-light limbo, the dead leg mambo, the go-and-get-pissed…All the steps are disappearing, one by one.’ Another, rather mournful Chopin Prelude now, and over the top Houstoun plays the end of a telephone message on her cassette player: Cheers then, lots of love which she rewinds and plays over and over again while bleached family photographs display on the screen. It is an act that has the poignancy of autobiography.

We are on to end-of-life questionnaires on the screen: Did you find your life experience a) satisfactory or b) unsatisfactory? Your opinions are important to us. Another abortive disappearing trick leads to the sound of a woman sobbing overlaid by a voice saying, ‘Preview’. Houston tries one last time to disappear — in vain — before delivering a Shakespearean epilogue imagining the visible specks of dust floating in the spotlights are living entities from beyond who may ‘tell us things we need to learn.’ She places her microphone in the air and manages to pick up scraps of speech and thoughts, not always welcome. This is where the political speech on austerity begins, and Houstoun sits it out under a light at the back, doing a seated soft-shoe shuffle. Acts 47 and 48 flow into one another as the clock ticks inexorably. By Act 49 she is still seated as if in a waiting room. There is a drum roll, but no action. We reach Act 50. Houstoun is gently nodding. On the screen a series of suggestions on how to finish the act scrolls down the screen (more slowly, as time has taken a break). I could sidle off into the shadows…sing a gently lullaby so everyone feels cared for…rage against the dying of the light…like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore…recite a poem. No, that would be too wordy. Lights out. It is the performance of a lifetime.

Posted: November 3rd, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Candoco Dance Company, Chahine Yavroyan, Imperfect Storm, Javier De Frutos, John Avery, Nicole Fitchett, Robert Rauschenberg, Set and Reset/Reset, Studies for C, Three Acts of a Play, Trisha Brown, Wendy Houstoun | Comments Off on Candoco Dance Company: Three Acts of a Play

Candoco Dance Company: Three Acts of a Play, Laban Theatre, October 17.

Annie Hanauer and cast in Set and Reset/Reset. Photo: Hugo Glendenning

Programming is everything in a triple bill; it can be an uneasy alliance of repertoire and new work, an indigestible three-course meal, or it can be like three acts of a play, an analogy Candoco Dance Company adopted for its most recent triple bill. Two of the acts are welcome re-stagings — Trisha Brown’s Set Reset/Reset and Wendy Houstoun’s Imperfect Storm — and the third is a new duet for Mirjam Gurtner and Dan Daw, Studies for C, by Javier de Frutos.

I saw Set and Reset/Reset last year in the company’s Turning Twenty program and thought it suited the company beautifully. It still does. Robert Rauschenberg’s design floats above the stage, though it seems there is a little less floating than before. Even though there is a structure to the choreography, the dancers seem to walk or run on as the spirit takes them, joining in Laurie Anderson’s musical procession that strolls down the west coast of California with its bells, assorted sirens and vocal improvisations in a spirit of carefree timelessness. There is a seductive dynamic of improvisation in the dance, too, a freedom of movement in which the dancers bump into each other and ricochet off each other with singular unconcern. The wings are of diaphanous material so we see what is going on off stage as well as on, a spatial continuum that Brown clearly enjoys and which is enhanced by Chahine Yavroyan’s lighting. The dancers are quite at ease, partly because the choreography is at ease and partly because the dancers have contributed to some of the choreography in the creative re-setting process. ‘Go with the flow’ seems to be the philosophical underpinning of the work, with its random connections, playful exits and entrances and a lightness that comes from Brown’s joy in exploring the air. As might be expected, there is no purposeful ending; the music fades away into the distance and the dance continues until we can no longer see it.

Dan Daw and Mirjam Gurtner in Studies for C. photo: Hugo Glendenning

Studies for C is pure magic. The setting suggests a domestic hearth with a carpet and two chairs, drawn in to an intimate space by de Frutos’ own lighting and haze, but the context suggests a wrestling ring with Daw and Gurtner fully masked and wearing leather jackets covered in painted phrases like ‘Better to Die’, and ‘The violets in the mountains have broken the rocks’. The inspiration is more Tennessee Williams’ Camino Real than Becket’s Waiting for Godot, but the songs by Lila Downs take us definitively to Mexico. In this rich juxtaposition of influences, Daw and Gurtner converse or argue with mute passion in their carpeted ring, giving a rich reading of the characters. The effect of the masks pushes the physical element to a stifling pitch of psychological intensity. Gurtner is mad, and flies across the floor. Daw is upset and stands truculently with his hands on hips. They are a couple that feels trapped by their familiarity, and struggles in vain to break free. The masks add an insectile quality to the characters and the inclusion of the song of La Cucaracha suggests two cucarachas down on their luck going through their death throes, legs in the air, trembling on the edge of extinction. They crawl over each other, Daw pulling at Gurtner’s mask. She kicks him, he howls and after a semblance of compassionate support, the two retreat to their respective corners to the lament, Yunu Yucu Ninu. Gurtner starts to take off her mask as the lights go down. Will she break free? We never see her face.

Victoria Malin in Imperfect Storm. photo: Hugo Glendenning

Annie Hanauer takes the microphone at the beginning of Wendy Houstoun’s Imperfect Storm, surrounded by her group of actors. ‘Tonight we were going to do The Tempest, by Shakespeare. William Shakespeare. But we found it a little wordy.’ Deciding to act it without the text, the only way to get people on and off the stage is to use the stage directions, she explains, and to use lighting (by Chahine Yavroyan) to create a series of tableaux, like paintings layered with costumes. Enter Alonso, Sebastian, Antonio; enter Ferdinand and Gonzalo; enter Prospero; enter Boatswain. Miranda’s already at the microphone. John Avery created just the right music, and Nicola Fitchett found just the right ruffs, hats and other assorted costumes and props. Each character picks a vestige of costume from the overturned costume rack. Sound of storm and lashing rain. Daw puts on his Boatswain’s hat, while others are quaking from the storm, pitched and tossed across the stage. Alonso pulls in a string of lights and drapes then around the shipwrecked group. Victoria Malin begins to recite snatches of Prospero’s lines, which devolve into a commentary on the progress of the play (‘we got trapped in this corner…by lighting’) as three characters fight with two wooden swords and a coat hanger. Malin continues with a brilliant monologue on the courage to stay… while all the characters leave. She then describes the stages of a storm that Daw illustrates in an extended solo, dancing in the spotlight. It is wonderful, from feeling the wind in his face (stage 1) to leaves rustling (stage 2) to whole trees in motion (stage 5) and widespread structural damage (stage 7) by which time Daw is running around in a circle jumping and flapping his arms. Alonso and Miranda enter and Daw is carried off, exhausted.

For all its apparent chaos, Imperfect Storm is a sophisticated work with beautiful writing (Houstoun takes sophistication and writing to another level in her 50 Acts). Houstoun allows the dancers to be themselves on stage while playing a failed amateur drama group without hamming it up. What comes across is a work that seems built up from an acute observation of what the dancers can do, and with their creative cooperation: a work that is not imposed on them, but grows out of them.

We have arrived at the finale, the end. Hanauer muses on how best to achieve the ending since everyone has already left and there are no more stage directions. Perhaps the lights fade slowly to black, or the lights could go off one by one, or there could be hundreds of candles we could blow out, or someone with a torch and the battery runs down. Or perhaps…

And as she continues to muse, the lights go suddenly and convincingly to blackout.

Posted: October 31st, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Dance Umbrella, Haunted by the Future, Mike Winter, Nigel Charnock, Shahar Bareket, Talia Paz | Comments Off on Nigel Charnock: Haunted by the Future

Nigel Charnock: Haunted by the Future*, Dance Umbrella, Platform Theatre, Central Saint Martins, October 13

photo: Tomer Applebaum

*Note: this performance replaces Ivo Dimchev’s Lili Handel which has been cancelled due to personal circumstances.

I am sorry to have missed Dimchev, but the opportunity to see Nigel Charnock’s last completed work in a festival dedicated to his memory is a ‘consummation devoutly to be wish’d’ both for Dance Umbrella and the audience. Haunted by the Future is about a consummation that is no longer devoutly to be wish’d – far from it – and it is nevertheless consummated with that abundant, overflowing energy and passion we know from Charnock’s own abundant, overflowing energy and passion. The universe will never be the same now he is out there.

But here in the relative pinpoint of a Platform Theatre, Talia Paz and Mike Winter dig into Charnock’s material with rubber gloves and claws to deliver this orphaned work in the presence of a doting, devoted public with such channeled energy that it might be impossible to ever replay it. Winter clearly has the harder task as Charnock wrote himself into the part. He is second generation but there is no doubt he is his father’s son. Paz, who also produced Haunted by the Future, is in a league of her own, free to embrace the work with her heart, her intelligence, her richness of expression, and a second position extension that has more meaning than anything ever seen on the stage at Covent Garden.

The uncompromising symmetry (of another dimension entirely to Beth Gill’s Electric Midwife) of the opening sequence where Winter drags Paz on to the stage struggling in a voluminous sack and the ending where Paz stuffs Winter into the same sack and drags him off is too premonitory to pass over. Is this the future Charnock was haunted by? It suggests the two characters are twin aspects of Charnock’s own persona: the love and hate, the fighting and making love, the need to be held and the need to stand alone, the need for understanding and the need to tell the world to fuck off; the desire to go back as much as the desire to go forward, in control and out of control, hurt and consoling, blindly passionate and searingly honest. Poignant, funny and hysterical by turns, it is the extraordinary performance by Paz and Winter that brings all these contrary aspects into one articulate, warm, flesh-and-blood whole that makes us realize how much we shall miss Charnock’s brand of no-holds-barred theatre now he is no longer on our stage.

There is his eclectic range of recorded music, from the chaotic mix of the opening five minutes to the sublime voice of Kathleen Ferrier — to which Paz dances a lovely flowing solo — via the nostalgia of Fred Astaire, Edith Piaf, Barbara Streisand, the whistling Ronnie Ronalde, a klezmer band and the soulful James Brown; the bare stage but for a few props, like the large sack, a rolled-up duvet that doubles as a flaccid dildo, a couple of chairs, clouds of ever-dispersing smoke; a disco ball emitting rays of sparkle in the opening sequence (lighting by Shahar Bareket); for each contestant in the matrimonial ring a bottle of water, a towel and a megaphone with which they harangue each other across the stage; the action running off into the audience, the screaming, the rants and the touching ballroom-to-crawling duets of a sexual, combative, face-slapping, bum-rubbing, hand-swinging relationship; and throughout Charnock’s irreverent, impish, to-hell-with-you sense of humour.

Haunted by the Future is a fitting tribute to Charnock, in his own hand. Who else could have done it better? One might almost say he was there, egging on Paz and Winter to their limits, which they surpassed. There are no half measures in Nigel Charnock; there never were and there never will be. Wherever he is.

Posted: October 29th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Anna Mae Selby, Baptiste Bourgougnon, Damian Goddard, Forgetting Natasha, Heather Eddington, Josephine Darvill-Mills, Kit Monkman, KMA, Melissa Spiccia, Tom Wexler | Comments Off on State of Flux: Forgetting Natasha

State of Flux, Forgetting Natasha, Patrick Centre, Birmingham, October 25

Melissa Spiccia in Forgetting Natasha photo: Chris Nash

I should start by saying this may constitute a conflict of interest and an egregious case of self-promotion as I am rehearsing State of Flux’s new work that will première in the Jerwood DanceHouse in Ipswich at the beginning of February. There, I’ve said it. We have been rehearsing for the last week in Birmingham’s Patrick Centre, where DanceXchange presented State of Flux’s Forgetting Natasha on Thursday and Friday. We ‘front’ the performance with a public sharing of the fruits of our first week of rehearsal, after which I scuttle into the audience to watch the show, which I am seeing for the first time although it has been touring to critical acclaim over the past two years. My six-day experience of artistic director Heather Eddington’s creative process has undoubtedly influenced the writing, though after the sharing her process is no secret.

Forgetting Natasha is about remembering: the nature of memory, what it means to lose it, the attempt to recapture it, and the effects of its loss on the individual and those around him or her. The further back the events and the stronger the emotions, the easier they are for Natasha to remember, but as the remembered past drifts closer to the present, so events lose clarity and form. Although Natasha is played by three performers (Melissa Spiccia, Josephine Darvill-Mills and Baptiste Bourgougnon) so as not to identify her too closely with any one person or gender, it is Spiccia who principally inhabits her with a bewitching mix of frailty and passion. All three are dancers by training, so they bring a broad and confident movement vocabulary to their acting roles.

I am reading Jonathan Meades’ collection of criticism, Museum without Walls, in which I came across this description of the relationship of memory to place: We create, often without realizing that we are doing so, narratives of our everyday topographies – these are personal to us and mnemonically potent. The shaping of memory and imagined memory, of self or the self we longed to be, of self in relation to place as much as in relation to people…Nostalgia is a basic human sentiment. It literally means merely the yearning for a long-lost place we once knew.[1]

It is the narrative of Natasha’s life that is unraveling. Eddington’s original stimulus for Forgetting Natasha was thinking about how memories shape who we are and how they, like places, become the pegs on which we hang our identity. When memories disappear, we become disoriented and lost. This is doubly so in Natasha’s case because, as she says, ‘When they first told me I was losing my memory I was petrified. I wrote my whole life in a book. Where the fuck have I put it?’

As Natasha shines a pool of light on the definitive moments in her life, her alter egos relive them as cameos: crying because she can’t go to Nana’s funeral; a snail race; her teacher – the big, fat Mr. Clues – who said she wouldn’t come to much; going to art school, getting kicked out for smoking pot (‘Everyone smokes pot; why did I have to get caught?’) and wondering how to tell Mother; leaving home for the first time; her first commission; losing her virginity; love, betrayal, and marriage; the birth of her daughter and their subsequent, strained relations. Bourgougnon and Darvill-Mills portray these beautifully. Then there is a moment when we realize we no longer have a perspective on the past; it is merging with the disintegrating present.

This is not the story of any particular individual; Natasha’s memories are gathered from the performers as part of the creative process in which each writes down or improvises their recollections. It is then the task of poet, Anna Mae Selby – a long-time collaborator of Eddington – to sift through these memories and create a consistent language and a credible narrative, like a collage of memories that threads through the work. Memory is thus the underpinning of the work, and one of the means by which it is informed. Eddington’s principal role is to direct the diverse creative talents towards her vision for the work, and she also provides the input of the dance sequences – fluid, lyrical and at times explosive – that are themselves analogous with memory: transmitted, learned and expressed through muscle memory, an ephemeral bridge between the mind and body.

Eddington evokes Natasha’s nostalgia not only in the beautiful text by Selby but also in her choice of music (tracks from Balanescu Quartet, Murcof, Sylvain Chauveau, Deaf Centre and Ludovico Einaudi), the lighting by Damian Goddard and in the immersive projections by Kit Monkman and Tom Wexler, aka KMA. Images are projected on to a backdrop and a front scrim, giving them extraordinary depth. As a particular incident is remembered, the performers may relive it within an isolated frame of light like a window on the front scrim – as when Baptiste reenacts the snail race – or fleetingly within a moving page of a diary. On the backdrop, family photo albums or 8mm movies with grainy images pass by with dates and annotations, images of scribbled notes on paper: all the paraphernalia we use for recording events. As Natasha says, ‘I am searching. Life rushes past me. Sometimes the most enjoyable thing about doing things is remembering them.’

As the work progresses we get closer to the heart of Natasha’s whirlwind mind, with her struggle to remember, her frustration at the gradual loss of any mnemonic reference points. Here the visual animation comes into its own, not simply as illustration but as an integral part of Natasha’s process. Images are reminiscent of banks of data bytes with their potential to corrupt, brain functions, and the flurries and eddies of thought as they escape from Spiccia’s mind like bubbles under water or snow flakes in a storm or a swarm of bees, all brilliantly coordinated with her actions. One section of Forgetting Natasha is given over entirely to the animation, a depiction of a fluid universe of memories like the Milky Way that swirls and sweeps across space.

As the effects of memory loss deepen, and the anchors of daily life get pulled from their sea bed, Natasha can’t remember who her daughter is, nor the strange man who always tries to get into her bedroom; she rejects both her daughter and husband and becomes angry when they remain in her house. She finds a note in her pocket on which is written Your name is Natasha. She looks puzzled. ‘I don’t know anyone named Natasha.’

She is haunted by the memory of the book, and continues to search for it. It is under her nose (Bourgougnon runs on with book to place it before her) but outside her grasp (as Spiccia reaches for the book, Bourgougnon passes it to Darvill-Mills). The cruelty is in the games the mind plays with us. Once Natasha has finally laid hands on the book she cannot decipher it. She reads a letter she had written to her daughter, saying this disease would take her daughter away from her, and her away from her daughter. But she no longer knows to whom she was referring. ‘I’ve always wanted a daughter. I would have called her Isabelle. We had fun today. Who is that girl in the photo?’ The events in the book no longer make sense to her, but she is unaware that this book is all she has left of her fragile self. In the final moment, she sees someone hovering in the shadows. ‘Is this your book?’ she asks.

[1] Jonathan Meades, Museum Without Walls, Unbound, p 20.

Posted: October 26th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Alexandru Catona, Andrea Catania, Aurora Lubos, Benita Oakley, Charlotte Vincent, Greig Cooke, Janusz Orlik, Leah Yeger, Liz Aggiss, Motherland, Patrycja Kujawska, Robert Clark, Ruth Ben-Tovim, Scott Smith | Comments Off on Vincent Dance Theatre: Motherland

Vincent Dance Theatre, Motherland, The Point, October 11

Andrea Catania and Benita Oakley

Life is a messy business, starting, as Charlotte Vincent does in Motherland, with menstruation. Aurora Lubos, elegantly dressed in black evening wear and high heels walks on to the bare, white stage with a bottle of red wine. She unscrews the top and slops it against the pristine backdrop at seat level: a dripping red splash. She puts down the bottle, hitches up her tight skirt and slides her back down the wall until she is sitting over the red stain. She remains there for a moment looking at us, challenging us to accept what she is representing. Soon after, an exhausted Andrea Catania walks in and collapses on the floor, like a bag from which the wind has been suddenly removed. Patrycja Kujawska walks across the back playing an elegy on her violin for the two women. It is a sequence that repeats throughout Motherland, Vincent’s examination of ‘the complex internal and external relationships that women have with their bodies, with their sense of self and with men.’ The latter are represented a few seconds later by a carefree Greig Cooke who walks on with his bottle of wine, smiles at us as he unscrews the top and takes a swig before continuing on his way.

I heard a little of Vincent’s pre-performance presentation in the theatre lobby by four young women reading and declaiming their hopes and determinations for their future growth. One of them mentioned a desire to be equal to men, to be respected in society for who she is. It reminded me of a quote attributed to Marilyn Monroe: women who seek to be equal to men lack ambition. In other words, if men and their example are simultaneously a benchmark of success and a target of criticism, being equal to men carries within it a paradox. In Motherland, however, Vincent has no truck with this paradox, destroying it in one blow by altering the creation myth: once Eve is with child, Adam is transformed into the serpent. In a form that is somewhere between a modern-day morality play and a cabaret, Motherland, written by Vincent and her co-writer Liz Aggiss, with the collaboration of dramaturg, Ruth Ben-Tovin, sees the sexual revolution from an unashamedly female point of view, and for men it is a wakeup call.

Vincent states in the program that Motherland is driven by sex, birth and death, though death takes up very little space compared to sex and birth. A principal leitmotif in the work is the association of female fertility with that of the land. The two are embodied by Lubos with a bellyful of earth hitched high up in her skirt that she empties on to the floor at intervals throughout the work: more mess. This earth becomes the land that Andrea Catania is toiling to nurture, like countless women around the world. At one point the entire cast joins in a ritual fertility dance to the accompaniment of Scott Smith on guitar singing Ready for Green. As Smith sings of ‘sowing the seeds of joy’ Cooke is screwing Catania on the ground. Making love might be stretching the imagination too far: the fertility cycle is in progress, but Catania is soon abandoned by Cooke, crawling off unnoticed to a corner of the stage next to a blackboard on which Cooke had written MOTHER in big letters. Vincent is not sparing on the irony.

Another, more urban illustration of the fertility cycle shows Lubos and Janusz Orlik arriving for a picnic, with a hamper and the Sunday paper. They relax on the grass, but instead of reading, Orlik takes prodigious amounts of cotton wool from the hamper and stuffs it under Lubos’s dress to a high-decibel distress signal played by Alexandru Catona on a gong. Lubos screams in pain. Kujawska appears holding up a speaker through which we hear applause. Orlik stuffs more cotton wool into Lubos’s expanding dress. She screams again and there is more applause, after which everybody takes a bow. Orlik’s newspaper is now stained with blood. Lubos pushes away both Orlik and Catona (more canned applause) and she takes a solo bow. She kisses Orlik and runs off. The applause continues.

Although men are an integral part of the fertility cycle, their social role comes in for particular censure in Motherland. Consider the depiction of carefree Cooke when he pulls down his zip and knowingly extracts his…banana. He peels it and eats it with gusto: no need to look up Freud’s interpretation. Retribution comes to Robert Clark when he opens his wooden box and pees into it; he carelessly closes the lid on his dick and screams in agony. Pulling out a blackened banana from his flies he begins to eat it, but loses his appetite.

Elsewhere, men are depicted as sleazy purveyors of sexual innuendo in the Manhood Music sequence, and generally as congenital misogynists who take advantage of women for their own pleasure and gratification. While it is the women in Motherland who punch their emotional weight, only the men dance. Cooke dances as if he is the master of his destiny, a charismatic charm offensive with his elaborate reverence and sleight of hand, but he is unaware that he moves in a series of hesitations; nothing is fully realised, and in his eyes is a look of perplexity. This contradiction is expressed after he plants Catania in the earth when he says excitedly to her: ‘I’m in control. I’m here for you right now’ after which he immediately abandons her. Only Clark is allowed any signs of compassion towards women. His duet with Lubos has a tenderness that is perhaps the one concession that men can behave with respect towards women. Not even this, however, can save the three men later from crawling like serpents through the earth on their way to hell.*

Robert Clark and Greig Cooke

Men playing women get more sympathetic treatment, as Orlik performs a drag routine that has Janowska applauding again. (When she attempts the same routine a little later, she ironically raises no laughter and no applause). Two men who play a rather privileged if tainted role in Motherland are Catona and Smith, the two-man band of troubadours, clowns and accomplished instrumentalists that adds both a lyrical and poignant element to the tableaux, making Vincent’s uncompromising stance more palatable. What lends this polemic of the sexes an air of authority, however, is the introduction of two key characters: 12-year-old Leah Yeger, through whose eyes the world of men and women is filtered and absorbed, and 75-year-old Benita Oakley, whose accumulated experience provides a sense of perspective and dignity.

Yeger is the one who arrives at critical moments in Motherland to question her colleagues, and thus forces them (and us) to examine what they are doing and why. It is her simplicity and lack of antagonism to either sex that brings people together. She tames Clark, who protects her and it is she who signals a truce to the (hilarious) slow-motion battle of the sexes (in which Catona excels as a victim of the invincible Kujawska), and rallies everyone together for a rousingly beautiful rendition of Woodie Guthrie’s children’s song, Why Oh Why.

Oakley’s contribution is based on her own experience. She begins her story lying on her side on the earth, with her head propped on a brown velvet pillow. Smith gives her a microphone and then accompanies her story on guitar with Catona on harmonica. She talks of her first pregnancy in 1956 and the difficulties she faced being unmarried. Lubos is making baby gurglings into the microphone on the other side of the stage. As the baby girl is born prematurely, she is taken away from her mother until she becomes stronger; Oakley cannot stay with her. She sleeps in the open but visits her baby regularly to give milk, until she can take back her baby with her. Oakley is dignified and calm, and every word has the unadorned simplicity of truth. After she finishes her story, she crawls back with slow deliberation to stuff the cushion back in its box, and carries it off like a memory. The second part of her story occurs a little later. She outlines her mouth with imaginary lipstick, pulls out her long silver hair, remembering how beautiful she was (without realizing how beautiful she is), feeling her figure and stomach. She relates the births of her next two children, in 1957 and exactly twenty years later. Both daughters are in the audience.

The function of a morality play is not to preach as much as to encourage or actively promote reflection on our present condition. There is much to be done, and many pitfalls still to negotiate, like the relation between wanting to be attractive and becoming an object of attraction and confounding a product with its advertising values. As Yeger says at one point, ‘It’s not about the look; I’m a person.’ The presence of Yeger prompts a reflection on the future and Oakley’s story shows that what she has experienced has been happening for longer than we care to remember.

The piece ends as it begins, with its charismatic cast of characters parading on to the stage, with the men looking a little the worse for wear. Have we learned anything from what we have seen? The ultimate success of Motherland depends on it.

Motherland is currently on tour. See www.motherland.org.uk for details.

* I have amended this paragraph after seeing Motherland again in London in November. Its emotional coherence made the balance between men and women clearer.

Posted: October 19th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aakash Odedra, Akram Khan, Andy Cowton, Constellation, Cut, In the Shadow of Man, Jocelyn Pook, Michael Hulls, Olga Wojciechowska, Rising, Russell Maliphant, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Willy Cessa | Comments Off on Aakash Odedra: Rising

Aakash Odedra, Rising, Pavilion Dance, October 18

Before Aakash Odedra performs the three contemporary works on the program, he demonstrates his dance roots in Kathak. Nritta, meaning pure dance, is a variation he created for himself and for which he arranged the classical Indian music. In my previous post, I mentioned that dance is expressed in the intellectual, the physical and the emotional bodies. Here in Nritta, Odedra manifests them all in perfect harmony within the complex rhythm of the music. As he writes in the program notes, ‘Here the movements of the body do not convey any mood or meaning and its purpose is just creating beauty by making various patterns and lines in space and time.’ It is pure dance.

Just perceptible in the smoky apse of light is a figure with his back to us, dressed in loose, grey cotton kurta and pants, his body still but for his arms and hands rising slowly, palms and gaze turned upwards as if offering a libation to the gods. The dance develops with dizzying, virtuosic turns – there is something of a Dervish in Odedra – and his lightning movements of the torso and arms make those statues of Shiva with multiple limbs make sense. How else can you capture this kind of movement in a statue? I had always thought of Kathak as grounded, with upward movement expressed in the body as an opposition to the energy directed into the floor, but the name Aakash means sky, and upward for Odedra means airborne: it is part of his personality, a trait his teacher in India recognized and encouraged. He has a slight frame, taut and elongated, so there seems to be no apparent force in his dance; what comes across is his love and thrill of movement and his freedom to jump and turn effortlessly around a still point. It is the physical expression of being in the moment.

Odedra does not come to contemporary dance through training in contemporary dance. He comes to contemporary dance through his training in Kathak. This makes his collaborations with Akram Khan, Russell Maliphant and Sid Larbi Cherkaoui a unique occasion. Khan has already developed a remarkable body of work from the same dance roots, so creating a solo on Odedra is a fast track process to a place way beyond the beginning. In the Shadow of Man is indeed a work that challenges Odedra in ways he may never have imagined, but his sensibility and integrity, not to mention his innate virtuosity, rise to the challenge. In the program notes, Khan muses on their shared Kathak tradition: ‘I have always felt a strong connection to the ‘animal’ embedded within the Indian dance tradition. Kathak masters have so often used animals as forms of inspiration, even to the point of creating a whole repertoire based on the qualities, movements, and rhythms of certain animals. So, in this journey with Aakash, I was fascinated to discover if there was an animal residing deep within the shadow of his own body.’ I don’t think there is any doubt that he found it, and the way Odedra reveals it is remarkable.

The opening image is difficult to make out, a shell or shield of an insect that is alive in that expressionless way insects busy themselves with the act of living: a movement of the eye, a leg, an antenna. But as the lighting of Michael Hulls gradually reveals this shield, we see it is Odedra’s crouched, naked back, and the insect eyes are his scapula rippling under his skin and the antennae his elbows. Jocelyn Pook’s score is suddenly riven by a piercing shriek from Odedra taken on the inbreath, scorching the lungs. He comes alive, unfolding like a wild man and stretching out his angular arms and legs like an emaciated saint stretching. The lighting picks out these body shapes, following the tearing movements of this hunter-gatherer, mouth gaping and blind eyes engaged. As in Nritta, we see the velocity of the turns, the arms whipped into the form of a double helix, and then the stillness. The insect develops into a loping monkey, to which the hissing and shrieks now belong, as do the whirling arms at the limits of Odedra’s circling torso, and the arching backbends that put his wild eyes upside down staring at us: traits of the atavistic figure consumed by the animal Khan has embedded – or revealed – in him. Pook’s score adds a sense of calm and order, rounding off the corners without disturbing the angular, feral nature of the beast. What gives this performance an otherworldly quality is the lack of any ego; Odedra has given himself over to the dance, and his bow at the end is one of genuine humility.

In Russell Maliphant’s Cut, Maliphant doesn’t so much create movement for Odedra as structure it. We see Odedra’s undulating, double-helix arms, his ability to rise from the ground as if pulled up by an invisible thread, his lightning dynamics, his ability to spin and his generosity of spirit. What distinguishes Cut – and gives it its name – is that Maliphant has Odedra dance with the light patterns of Michael Hulls which cut his body into zones of light. Hulls is a visual magician, creating a virtual scrim of light and smoke through which Maliphant thrusts and weaves Odedra’s movements, first his hands and arms and later his full, whirling body. The lighting also supports Odedra’s gestures, as when he pushes down magisterially on two columns of black light that are the vertical shadows underneath his own hands. A third element is Andy Cowton’s score, which is as intimately related to the choreography as the lighting. When Hulls’ triangle of light takes on three dimensions, opening up a vista of latticed blinds on the floor, there is a suggestion in the music of the blinds opening and closing as Maliphant contrasts Odedra’s crawling motif with the horizontal bars of light. Hulls rolls up the blinds leaving Odedra in silhouette in open space, and then raises the lighting level so only his skin is visible as his clothing blends into the smoky light. The final sequence is pure Odedra, whirling fiercely downstage across the blinds and arriving at a stillness in which he grasps the shadows of his hands and pushes them down once again, keeping his dark gaze on us, as he turns up his palms and closes his fingers slowly into a fist.

The order of the program is decided more by the technical aspects of the lighting than by a considered approach to the choreographic content: a little bit too much of the lighting tail wagging the choreographic dog. The last work, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s Constellation, is the most mystical of the three, and belongs more in the middle than at the end, except for its lighting demands. It is also the work in which there is less of Odedra’s own movement vocabulary and more of Cherkaoui’s conceptual framework: a constellation made up of patterns of sound and light with Odedra as the locus, an ‘astral body generating its own rhythms and luminosity.’ The rhythms are provided by the lovely score of Olga Wojciechowska, and the luminosity by Willy Cessa’s suspended light bulbs of differing intensities that provide the only illumination for Odedra’s motion. He is more a presence in Constellation than a performer of Cherkaoui’s movement phrases. At one point Odedra swings a single bulb in front of his head that illuminates the alternate sides of his face as it rotates, like two phases of the moon. Constellation is a meditation on space and spirituality, and Odedra provides a performance of mystical serenity. Towards the end he sits in meditation and instead of Cessa’s lights fading to black at the final moment, they all increase to full illumination. How appropriate.

Posted: October 17th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Beth Gill, Dance Umbrella, Electric Midwife, Jon Moniaci, Madeline Best | Comments Off on Beth Gill’s Electric Midwife: Lost in translation

Beth Gill, Electric Midwife, Platform Theatre, Central St Martins, October 9

Perhaps I am not sitting in the right place – not directly in the centre and too close to the front – or perhaps the theatre is just too wide, but for some reason Beth Gill’s Electric Midwife, presented by Dance Umbrella at the Platform Theatre of Central Saint Martins, is not translating well. In a work so totally committed to the mirror symmetry of six performers in two trios, the question of viewpoint is crucial, because if the symmetry is not evident, there is little else to appreciate. Where symmetry is often valued in a context of non-symmetry – the country house in its parkland, a corps de ballet in a narrative setting – Gill explores symmetry as the sole choreographic underpinning of Electric Midwife, relying on its visual aspect above all others. Gill, it seems, has always found it interesting to present her work in a visual art capacity.

The piece opens as the audience arrives, with the two trios of dancers against the wall on either side of the bare stage, matching their poses in mirror image. There are two taped, black tramlines, the width of a chair, running up the middle of the stage from front to back. The dancers, all women, are in practice clothes; there has been no attempt to create a symmetry of identical body shapes and there is some disparity in the amplitude of their respective movements. One dancer starts a movement, which is mirrored by her counterpart on the other side of the stage, though the stage is just too wide for me to see both at the same time. My viewpoint improves as the dancers approach the tramlines. Essentially, one trio is choreographed, and the other acts as its mirror image. When the dancers are in eye contact, there is a good chance their mirror symmetry is effective in both space and time, but when they are not, the beatless score by Jon Moniaci is not particularly helpful. Perhaps part of the choreographic process is to work out a telepathic sensory system between the dancers so they can initiate movements at the same time. Generally the timing is maintained remarkably well, though the errors are all the more evident and prove a needless distraction.

There are formations that remind me of the columned, sculptured entrance to a Baroque building, and at other times there are references to Michaelangelo’s ideally proportioned man in his circle, and shapes based on the first position in ballet. Patterns repeat, and there are a periods of stillness, but because there is no emotional force in the movement, these static forms have no life; the stillness has nothing to retain. Towards the end there is a promising increase in the dynamics of the work, as if Gill wants to bring off a final, juicy variation before the return to stillness at the end. Her symmetry begins to get a workout as the dancers have their first contact with each other, like a planar intersection, with a seated couple falling through the open legs of a standing couple. There is a feeling of a development here, but instead the music stops soon after and the dancers make their slow, symmetrical way off stage in a rose light.

Electric Midwife could fall into the meditative experience if it wasn’t for the intellect working so hard to perceive and appreciate the symmetry. The sound score by Jon Moniaci is certainly meditative and Madeline Best’s lighting reminds me in its opening gradations of a monochrome Rothko canvas. Interestingly, the lighting is the one element that forms variations on the symmetrical theme. At one point the overhead lights create intersecting circles on the stage, with the shadows of the dancers cast on them at asymmetrical angles. At another point the front lights project the shadows of the dancers on to the back wall, warping the floor symmetry out of alignment. The meditative aspect seemed to pick up in the latter part of the work, with the use of different mudras. A dramatic pose by one couple had something of a Bharatnatyam influence and the two girls ringing out ceremonial cloths into the bowls of water is perhaps another reference to Eastern meditative practice.

Dance includes the intellectual body, the physical body and the emotional body. At most Electric Midwife includes the intellectual and the physical, for there is little trace of the emotional (I don’t mean crying, laughing, fear and joy, but simply the emotional body which conveys the sense of dance). Without the emotional body there’s a kind of lethargy in the movement, like balloons with insufficient air. Electric Midwife is predominantly physical and intellectual, so the dancers don’t have much to do apart from being in precisely the right shape at the right time to retain the symmetry of the piece. It is essentially static. What is missing is the dynamic interaction of patterns, shapes and forms.

What a surprise, then, to see the video monitor in the bar area an evening or so later, showing a clip of Electric Midwife on a narrow stage seen through a single lens. Suddenly the patterns and their interactions make sense. It is like looking through a kaleidoscope as the dancers merge and disperse, form and reform in almost mechanical precision. Even without looking at the screen from directly in front, I could appreciate the patterns. Gill has made symmetry a guiding idea in Electric Midwife, but she has not, as the performance showed, overcome its visual limitations. But film, with its single, shared viewpoint, seems to resolve them very effectively.