Posted: February 17th, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Chandelle Allen, Corp de Ballet, Emma Cole, Francis Booth, Gail Gordon, Lindsay Dukes, Lullaby for a Lost Soul, Paul Chantry, Rae Piper, Ronald Corp, Songs of the Elder Sisters, The Yellow Wallpaper, Village Underground | Comments Off on Chantry Dance Company: Corp de Ballet

Corp de Ballet: Triple Bill, January 18, Village Underground, Shoreditch

Ronald Corp’s setting of verses from the Dhammapada is playing as we enter. The feeling is liturgical and as cavernous as the magnificent (but rather chilly) vaulted brick space that is Village Underground in Shoreditch. There are strips of painted wallpaper in fading yellow hanging like scrolls from the sides of the central vault that serves as the stage, and a double bed in an abundance of white at the end. Corp himself welcomes everyone, and explains the eponymous link between his music, which makes up the entire program of three works, Francis Booth, who wrote, translated or adapted each of the texts, and the choreographer, Paul Chantry of Chantry Dance Company.

The text of the first piece, The Yellow Wallpaper, is adapted from the short story by American author Charlotte Perkins Gilman. It is a nineteenth century semi-autobiographical story about a writer who is persuaded by her husband to undergo a ‘rest cure’ (Gillman had in fact a serious case of post-partum depression following the birth of her daughter), involving confinement in a stifling room in a country house. It is story of a descent into madness as a result of the prescribed cure, and stands as a spirited protest against the medical profession’s oppression of women. Corp and Booth have divided the story into six scenes, which all take place in the same room with the yellow wallpaper. Chantry himself plays the husband, a sallow, dry-white character like an Ashton husband but with less blood. His stage wife is played by two people: dancer Rae Piper and actress Lindsay Dukes, who together mirror the dual personality misdiagnosed as dissociative psychosis. The two women are described in the program as Narrator (mind) and Narrator (body). There is also the beautiful, rich voice of Rebecca de Pont Davies singing Booth’s text — Corp scored the work for mezzo-soprano and string quartet — who is in effect a third narrator. A fourth character is the spirit of the wallpaper, played by wild-haired Chandelle Allen.

What is interesting is that Dukes, who doesn’t dance very much, feels more true to the character than Piper, who has rather too much unbridled dancing that owes more to a display of classical dance vocabulary than to harnessing that vocabulary to express the internal drama. The principle character, after all, is constrained; Piper in her range of movement is anything but. If the dramatic intelligence of Dukes could have informed the choreography, it might well have expressed something approaching the ambivalence of the text and the tensions clearly expressed in the score. I believe this is what Chantry intended, but it didn’t manifest; instead the choreography lies rather too self-consciously on top of the music, which is strong enough to support it but gains little from the association.

Lullaby for a Lost Soul is a collection of short poems by Booth on the theme of loss, grief and helplessness. Corp has set it for counter tenor, cello, vibraphone and flute in the manner of John Dowland. Booth’s poems take the myth of The Fall as a metaphor for the dark emotional hole into which we may descend at a time of loss and grief. Chantry follows the metaphor rather too literally, taking the figures of Adam and Eve as his structure for this duet he dances with Piper. Chantry’s choreographic imagination, based as it is on the classical vocabulary — and on Piper’s technique in particular — again defaults to a display that is more alphabet than lexicon. Chantry appears to have got his creative process the wrong way round. He needs to find the true emotional value and only then express it in form — classical or otherwise. The problem is that if the emotions aren’t embodied in the movement, they appear superficially in mime — rather too often in a pained facial expression. There is also a curious inversion of the end of the tale. Adam and Eve were naked in their innocence and clothed themselves with the taste of knowledge. Here the consumption of the apple, replete with vampire-like smudged red lips, leads Adam and Eve to strip each other to the waist. Inverted half measures all round.

Francis Booth’s translation of five texts from the Buddhist Pali canon provides the setting of Songs of the Elder Sisters. Corp’s music employs the lovely voice of Rebecca de Pont Davies once again in a more religious, mystical setting with baritone, clarinet, alto flute and viola, and it sounds lovely in this vaulted space. Three acolytes (Piper, Allen and Emma Cole) are sitting in the presence of the nun, Ambapali, who is sharing her wisdom and advising her juniors on how to overcome temptation on their upcoming pilgrimage. The role of the nun is played by Piper’s mother, Gail Gordon, and once again her life experience and subtle range of dance movement makes her the focal centre of this piece. As with Dukes in The Yellow Wallpaper, Chantry has uncovered a strength in choreographic language that these two collaborators naturally offer and which might be a starting point for future exploration. When faced with too much flexibility and extensions, Chantry gives in to them rather than restraining them to adapt to his dramatic purpose or the nature of the texts. Piper may be the culprit here, but the choreography is the loser. Corp’s music and Booth’s texts are the overall winners.

Posted: February 14th, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Barret Hodgson, Be Like Water, Bruce Lee, Eva Martinez, Hetain Patel, Ling Peng, Michael Pinchbeck, Rich Mix, YuYu Rau | Comments Off on Hetain Patel: Be Like Water

Hetain Patel: Be Like Water, Rich Mix, February 2

As with the popular evolution of wine, dance has gone from its traditional forms through international styles to ethnic cross-fertilization. Hetain Patel’s Be Like Water is such a delight that it reminds me of a recent comment by a wine writer who said that thirty years ago the idea of the best-tasting burgundy coming from Hungary would have been unthinkable. Be Like Water’s humour and intelligence, conceived as a Bruce Lee-inspired autobiographical fragment by a Bolton-bred first generation Indian video artist and a Taiwanese dancer, make it one of the most refreshing works I have seen in a long time.

Patel is a visual artist whose video installation To Dance Like Your Dad was included at Dance Umbrella last year. Parts of that installation find their way into Be Like Water, which was originally conceived as a video work but passed through several transformations before emerging as a dance theatre work with a multitude of elements and a deceptively simple path. All credit to Patel and Yuyu Rau for the text, and to Eva Martinez and Michael Pinchbeck for the dramaturgy, seamlessly weaving together a video tour of father Patel’s coach building factory with the son’s superimposed guide to his stage set, Bruce Lee with the erhu, China with Bolton and Kung Fu moves with Rau’s spirited solo of childlike enthusiasm that closes the performance.

As varied and beautiful as the individual elements of Be Like Water are, what ultimately holds it all together is the theme, which is contained in the title. In his To Dance Like Your Dad, Patel is clearly in awe of his father, and in Be Like Water he conjures out of the air the words Every now and then in my life I have tried to be like my father. Trying to be someone else has its hazards: as a student Patel adopts a fake Indian accent and grows his hair and moustache like his father which allow him to get a discount in Indian stores but he finds the moustache is so out of proportion to his own face that it makes him forget who or what he is trying to be. In imitating Bruce Lee he ends up in a police station for disorderly behaviour delivering a kick to a dustbin in the street (an action picked up ironically on CCTV). On a residency in China he learns a paragraph of Chinese from a Chinese woman, but discovers that he has picked up his teacher’s inflections (Patel has a particularly acute sense of mimicry) that make him sound to the Chinese like a woman. Throughout the work, Patel uses his self-awareness and humour to reveal these inconsistencies of expression through anecdote and well-conceived video work (with the aid of digital artist, Barret Hodgson).

At the beginning he speaks in Chinese — to avoid any assumptions, he says, about his northern accent — and Rau translates into English. He then admits what we have begun to suspect, that he only knows one short paragraph of Chinese that he repeats on all subsequent occasions with varying emphasis while Rau dissembles by delivering a consistent English text. Patel thus wraps himself up in disguises that fool nobody but himself. On the other hand, one senses his father, an Indian immigrant who speaks with a broad Bolton accent, has no need of disguise and is very much himself. Rau reminds us that Bruce Lee found in Kung Fu the only way he could most honestly express himself and Rau herself learned classical ballet as a child in Taiwan but only when she started studying contemporary dance in London did she find her true expression (which makes her final solo dance to erhu accompaniment so poignant). Patel’s moment of realization seems to come as he sits listening to Ling Peng ‘translate’ his Chinese into notes on the erhu. As Ling Peng plays (beautifully), a live projection of her hands on the bow arching across the strings expresses the oneness that exists between musician and instrument. It is as if Patel himself finds his voice in soaking up the influences of his collaborators, in assimilating his own experiences and in reaching his conclusions; he becomes one with his work. Be Like Water has the wisdom of a modern fable, expressed imaginatively and generously, speaking to us all.

Posted: February 7th, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Ann Dickie, Anna Selby, Dance East, GaiaNova, Heather Eddington, Jerwood DanceHouse, Laura Farnworth, Magali Charrier, Nicholas Minns, Pradeep Jey, Sarah Beaton, State of Flux | Comments Off on Heather Eddington’s House on the Edge: blogging from the inside

Heather Eddington: House on the Edge. First performance February 8, Jerwood DanceHouse, Dance East

photo: Chris Nash, Design: Tom Partridge

I have not been able to write about many performances so far this year as I have been working on a new production at Heather Eddington’s State of Flux in Ipswich. It is Heather’s House on the Edge, which has its first public outing this Friday, February 8 at Dance East’s Jerwood DanceHouse. In a recent telephone interview (it starts 49:33 into the broadcast) BBC Radio Suffolk’s Stephen Foster introduced me as the lead male dancer, which sounds rather grand; I am in fact the only male dancer and Ann Dickie, who plays my wife in House on the Edge, is the only female dancer. The third character is the actor, Pradeep Jey, who plays with great versatility both an envoy from the local council and nothing less than the sea itself.

Heather had asked me to add blogs on the creative process for her State of Flux site, where you can also see some photographs from a publicity shoot with Chris Nash and some of our own. Nearly all this material is copied from, or derives from that blog.

House on the Edge has its origin in the erosion of the Norfolk and Suffolk coastline that Heather knows well, and in particular the effects of erosion on the community of Happisburgh, What was once far from the edge of the cliffs is now closer to the edge, and what was once close to the edge is either in danger of falling or has already fallen into the sea. It is a very slow process where nothing appears to be changing until the invisible forces within the cliffs suddenly manifest. Heather’s narrative takes Happisburgh as a metaphor for living on the edge in a precarious balance between the physical (solid ground, security, responsibility, conventional wisdom) and the spiritual (the elements, the unknown, irresponsibility, intuition). Life is never either black or white, nor is this balance a matter of keeping to one side or the other. The elderly couple at the heart of House of the Edge — Edward, who has lived in the house all his married life and wants to stay and his wife Lucy who is torn between looking after her husband who has terminal cancer and accepting what the council calls managed retreat — are in a constant turmoil as to how to harness the elements that encroach on their precarious lives.

Much of House on the Edge is built up through the creative use of improvisation. The text by Anna Selby was sketched out during discussions and improvisation exercises last year. As a dancer, I had always preferred to be told what to do by a choreographer, but this new experience has been a revelation. My first improvisation was with Ann. It was a verbal improvisation in which her contribution was limited to one line, ‘We should leave’ and mine was limited to ‘We should stay’ and we had to continue until one of us conceded. I could not understand how this could possibly resolve, but it did. Since that first attempt, many of the qualities of our respective characters and of the relationship between us have been suggested through similar improvisations — some more successful than others — but each time there is something to learn. Verbal improvisation has led to physical improvisation to find external expressions of internal ideas. In the course of creating the work, some of these movement phrases have been reworked as set pieces and we go through an awkward phase of losing the spontaneity that improvisation gives until we find that spontaneity again in rehearsal and performance. Only recently did I realise that improvisation is at the heart of our entire social interaction; our goal in rehearsing is thus to return to this fundamental form of communication.

‘Here’s a poem. It is 18 lines long. Each line has between one and 10 words. Find a single movement or phrase for each line.’ This was my task one day, and I had the luxury of working in one of those beautiful studios at the Jerwood DanceHouse to complete it. A friend has cancer of the esophagus and thinking of her I found a phrase for the first line — ‘illness’ — quite quickly. ‘Eyes in the grass’ was another line I was able to translate, if rather literally. ‘Pouncing on you when you are relaxed’ was clear in my mind but I couldn’t find a way to do it physically. For ‘pushes you to a point of no return’, I had in mind something between a Martha Graham back release to the floor and an image of a sculpture by Ernst Neizvestny (from John Berger’s book, Art and Revolution). Others proved more difficult to approach: ‘us’ and ‘shapeshifting’ were two (‘bellyflop’ I didn’t attempt). By the time Heather came up to see how I was getting on, I had a repertoire to show her, though I was less than confident it would be of any use. She numbered each line and my corresponding movement phrase, making only one critical observation: I had to purge my phrases of anything from a previous choreography or style I had known. The Martha Graham release was out, but a little of Neisvestny left in. Then she said, ‘Put 1 and 3 together, then add on 6, then 4. ‘What have you got for ‘us’?’ I did the first thing that came into my head. ‘Great. Put it after 4. Repeat 1 from that position, then again kneeling. Add another 3, then a prolonged version of ‘shapeshifting’ into ‘moment of stillness’. She helped me find a way to ‘pounce’ and that was added on, followed by another ‘eyes in the grass’, ‘moment of stillness’ and ‘us’. Two variations of 1 (illness) rounded it off. While I had been working in the studio, Heather had been working in the theatre exploring material with Pradeep that she wanted to overlay on the Illness dance. The interaction between Edward and the Sea is a vital relationship in House on the Edge, and this weaving of the two characters became a key dramatic scene near the end of the piece. We ran the two together later in the afternoon.

Last Friday we ran the piece from beginning to end for the first time, in costume (by Sarah Beaton), working with the lighting and projections (by Magali Charrier with technical assistance from Ben at GaiaNova) and with various musical choices. Having worked on individual sections intensively for the past week (under the guidance of theatre director Laura Farnworth), it was difficult to maintain that intensity going through the junctions and intersections, but going from beginning to end with the occasional ‘where do I go now?’ gave us at least a physical and narrative arc on which we can work for the final week up to performance on February 8. We are beginning to inhabit the characters, to make them our own and that in turn informs our physical interactions. What remains is a process of further filling out of both character and movement, moulding all the elements together until they have a logic and arc — and a life — of their own.

Before starting the project I had not heard of Happisburgh and was not aware of this phenomenon of cliffs collapsing and houses falling into the sea. One of the first resources we dipped into was Richard Girling’s book, Sea Change: Britain’s coastal catastrophe, a good starting point. Last weekend I had a free day and decided to go to Happisburgh. Heather had already taken us to Dunwich to get a sense of the effects of coastal erosion, but most of mediaeval Dunwich is already well under the sea. Happisburgh is still a community of solid houses, a school, the Hill House Hotel, an operational lighthouse painted in bright bands of red and white, St. Mary’s Church and an Arts and Crafts era manor house. There is also a broad swathe of caravan park located between the village and the cliffs where at least one caravan stands perilously close to the edge. The cliffs are high and susceptible not only to the external battering of the sea but also to the internal buildup of groundwater. For now there are some sea defences in the form of rocks and wooden revetments, though the latter are in dire need of repair — or have they been abandoned? To counter the groundwater risk, drainage channels have been dug along the cliffs from which plastic tubes project at intervals to channel off the water. It is difficult to imagine the cliffs crumbling, but photographs and studies tell of the brutal reality. The edge of the coastline has been receding inexorably and unless human ingenuity and political will can together find a solution, this beautiful town may, like so much of the once-flourishing Dunwich, disappear under the sea. I fell in love with the place, as have many others before me, but I imagine it takes a certain stoic optimism and perseverance to live so close to a crumbling edge. Certainly my visit has given me images with which to work in preparing House on the Edge, and beyond that perhaps Heather’s work can draw more attention to the cause of preserving such beautiful towns and villages — and the lives and livelihoods of their residents — along the North Sea coast.

Posted: January 31st, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Brian Gillespie, Dinah Mullen, Independently Dependent, Ji-Eun Lee, Joseph Mercier, PanicLab, Play. Back. Again. Then, Resolution! 2013, The Place, Throb: A Cardiovascular Romance, Tim CJ Chew | Comments Off on Resolution! 2013: PanicLab, Ji-Eun Lee, B-Hybrid Dance

Resolution! 2013: The Place, January 11

PanicLab: Throb: A Cardiovascular Romance

A curtained cubicle in hospital green with a single pillow and a basin of water is not the kind of setting that immediately comes to mind for a work with the provocative title, Throb: A Cardiovascular Romance, but choreographer Joseph Mercier juxtaposes sexual and clinical connotations in this meditation on the proximity of love and care, life and death, light and darkness.

Based on Mercier’s personal experience, Throb: A Cardiovascular Romance is a celebration of a significant event in a commonplace, clinical environment: a carer guides his terminally ill patient through the final stage of his life. It is ‘dedicated to Erin Mercier and many others.’ Throb refers both to the relationship that develops between the carer (Mercier) and his patient (Tim CJ Chew), and to Chew’s heart which is suspended in a jar with a breathing red light that he keeps close to him at all times. As the supine Chew restlessly changes position, Mercier swiftly places the pillow under his head, the two tracing Escher-like patterns on the floor. As Chew’s movements are driven by discomfort, Mercier’s are always tender and solicitous, feeling Chew’s forehead and stroking his temple. As their intimacy grows, Mercier rests Chew’s head on his lap instead of on the pillow and they exchange looks, smiles and sotto voce conversation. The fragile cardiovascular meter glows intermittently, beats and fades, mirrored in the growing pliancy and languor of Chew’s body. We hear the sound of a dog barking but there is no danger in this quiet room. Chew takes off his clothes and Mercier bathes him with a flannel and (one hopes) warm water in the basin. There is a sense of a Pietà in the attitude of the two bodies, the one supporting and the other pliant in decline, though the powerful physical bond is contrasted with the banal sound of the weather forecast on the hospital TV (sound design by Dinah Mullen). Mercier helps Chew on with his clothes and lays down next to him. Their intimacy is highlighted with a kiss before Chew gets weaker and needs to be supported in his efforts to move around. The sounds of a game of billiards and teeth cleaning impinge on the quiet and then a music box plays. As Mercier moves Chew to a new position, Chew no longer has the strength to move his jar; it is now Mercier who holds his friend’s life in his hands. Chew motions to Mercier for his jar, which Mercier places in front of him. It is still faintly alight and beating, but not for long.

Ji-Eun Lee: Play. Back. Again. Then.

From a hospital cubicle we move into an abstract space delineated at its four corners by two dilapidated metal-framed, plastic-seated chairs stacked on top of one another, and a couple of roles of packing tape stuck or looped on to the upturned legs. It is an unsettling image of decay or abandon, yet when Ji-Eun Lee appears on stage as if by accident it is transformed into one of strange beauty and mystery. Lee is tall and thin with a serene, commanding expression that imbues every movement she makes with stillness and purpose. She is aware of her audience, confides in them and draws them inexorably into her intent.

She walks in cradling what appear to be three large oranges; one falls to the ground and she picks it up apologetically, only to drop another and so it goes on until she scoops them up into her skirt and sways across the stage like an exaggeratedly pregnant woman. The oranges are made of soft clay and she places each one carefully on the floor in a diagonal to one of the chairs, stepping back with exaggerated precision, one foot length at a time, crouching lower with each step, like a lioness about to pounce. She returns to her clay oranges and shapes one into a primitive human figure. She takes her time, time that is constantly slowing down to a ritual stillness. She concentrates on modeling each one in turn, working her fine fingers into the flesh of each, three incarnate forms. She steps back from her work and stretches her blouse over her head, looking at us as if through a shaman’s mask. She then marks out an arena by using each chair as a corner and pulling the clear tape from one corner to the next and on round three times. She climbs into her ring and places one clay figure on a chair at the back, and one on each of the front chairs. She now adds another level of meaning by marking out on the stage three small taped squares with an opening on one side with their openings facing each other. She hurries a little with the finishing of the third (the only inkling of an external constraint — the musical line — impinging on her ritual). She places each clay figure in its respective taped enclosure and surveys her work, regarding them each in turn. She responds to each with semaphoric arm signals, increasing the intricacy until she breaks into a beautiful whirlwind phrase of dance that seems to come out of nowhere, a rising storm that breaks and then reverts to stillness as suddenly as it starts. She collapses in front of one of her creations and looks at it with a private intensity, spreading her fingers, investing life into the figure. She frees it, placing it just outside its taped enclosure, and considers carefully. She looks at us to signal her desire to place herself in the enclosure. Having done so, she changes her mind: unlike her clay figures, she has the power to decide her own destiny. She looks at the figures, looks at us and makes her final move: out of the enclosure, out of the taped ring and off the stage. Play. Back. Again. Then is a breath of fresh air in which Lee has created a work of haunting beauty even as she questions her role as creator.

B-Hybrid Dance: Independently Dependent

An element of minimalism has pervaded the first two pieces. Mercier builds up his simple tale in broad pale green strokes with skin tones, while Lee’s work is more akin to calligraphy. Both are quiet and focused, but the final offering on the program, Brian Gillespie’s Independently Dependent, is neither one nor — more importantly — the other. There is no lack of movement among the six dancers but a serious lack of intent. Perhaps the program note threw me: ‘Independently Dependent…explores a girl’s transition as she is swooped from the comfort of childhood and engulfed by a system where independence and dependency go hand in hand. The pressures placed on this youth permits few things to pass into growth.’ The description on The Place’s website does nothing to alleviate the confusion: ‘A bitter-sweet performance in response to a following where innocence is stripped, imagination restrained, and simple play is modernised and materialised. Place in our code-ridden society conflicts with blissful childhood.’ With two such convoluted briefs it is no surprise the resulting choreography passes by without any apparent grasp of its own scenario. What is left is movement that is energetically inarticulate.

Posted: January 16th, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: A Readiness, Abi Mortimer, Aya Kobayashi, Carrie Whitaker, Dougie Evans, Joe Darby, Kai Downham, Lîla Dance, The Incredible Presence Of A Remarkable Absence | Comments Off on Lîla Dance: A Readiness, The Incredible Presence Of A Remarkable Absence

Lîla Dance, A Readiness, The Incredible Presence Of A Remarkable Absence, Pavilion Dance, November 29

Before Lîla Dance begins their own program, hoards of young children in orange costumes erupt on to the stage in two lines to form two circles. Their performance is neatly choreographed by Lîla Dance as part of their outreach program, but what I see is the children bumping, laughing, copying, wondering where to go, finding their places, seeing who’s in the audience, pulling up trousers, jumping, reaching, giggling, and stamping. As the little ones exit, their places are taken by slightly older children. Some are tentative, others have a natural presence on stage. Counting the beat with their heads, they keep in line, form and reform what could be one giant, moving school picture and keep their infectious energy bubbling until they all leave in enthusiastic disorder.

Lîla Dance is presenting two works of their own: a duet for — and created by — co-artistic directors Abi Mortimer and Carrie Whitaker called A Readiness and a new, longer piece based on Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot choreographed by Mortimer: The Incredible Presence Of A Remarkable Absence.

A Readiness sees both dancers at ease in a style of contact improvisation that has pace, skill, nerve and humour. The set looks as if it is inspired by an IKEA lighting catalogue: a variety of anglepoise and desk lamps, with one naked light bulb suspended on a long cord. There is no plot but rather a series of games in which one performer dares the other to join in. They support each other, knock each other over, bump each other as if attached by elastic, take each other’s weight, hold on to each other like hooks, catch each other from running, embrace, change impulsively from pose into movement like two clowns playing a skillfully choreographed game of follow-the-leader. The score is a collage of recorded sounds by Dougie Evans (a third co-artistic director of Lîla Dance): tram bells, doorbells, foghorns and falling water, played forward and backward, that work their way subtly into the improvisation. Whitaker is like the water and Mortimer like the resultant electric current; together they form a seamless, continuous, mutual support framework. At one point Whitaker crawls like a crab under one of the lamps to take a breather, but Mortimer is not having any of it. ‘Ready?’ she asks. ‘Yep’, answers Whitaker, jumping up to start another game, as they push and needle each other. Mortimer and Whitaker play on their differences; Mortimer the driver is the more frenetic and needy, while Whitaker appears the stronger and more phlegmatic of the two. The movement celebrates those differences and the two characters are fully developed here in what is on one level a very casual, playful interaction but one that comes alive through rigorous execution.

The Incredible Presence Of A Remarkable Absence sees Mortimer stepping out of the action and creating choreography on a quartet of dancers: Aya Kobayashi, Joe Darby, Kai Downham and Whitaker. Inspired by working with Simona Bertozzi, it is the first time the company is incorporating text and theatre into the dance element. The score is again by Dougie Evans, providing an eclectic mix of sourced sound, some rather mournful strains of mandolin and brass against the soft crackle of campfires with snatches of birdsong, Jimmy Rogers singing Waiting for a train and a lovely passage by Evans himself on slide guitar.

I saw The Incredible Presence Of A Remarkable Absence twice; the first on opening night at The Point in Eastleigh, and the second here at Pavilion Dance. There was something that didn’t work for me on the opening night though I couldn’t put my finger on it; I wanted to see it again to clarify or refute my original reservations.

There are advantages and disadvantages to relating the piece to such a milestone of theatre as Waiting for Godot, but they are not central to an appreciation of the work itself. What is central is the way it is played. My first impression was that Mortimer and the cast had made Beckett too cuddly, too soft; the images are of a comfortable desperation, a bearable absurdity. On my second viewing this feeling remained, but it was related to something more essential. The defining moment for me was when the clean-cut, elegantly-costumed Downham blurts out the line “All my lousy life I’ve crawled about in the mud” with nothing in his appearance, behaviour or demeanour to suggest the truth of his statement. Suddenly the discomfort I had felt about the piece clarified: the four characters are simply not sufficiently defined for the performers to develop them. The cast members, who have no lack of spirit and no inability to move, are thus confined to playing themselves with standardised tropes instead of getting inside their characters. Without the development of character, their actions tend to meander to the end at the same level with which they start and although there is a comic element, it comes across as incidental and disembodied because it has no character or action to support it. A Readiness has no such problem because of its abstract nature, and as such there is an integrity between choreography and performers. The Incredible Presence Of A Remarkable Absence derives from A Readiness but fails to metamorphose into theatre.

Posted: January 2nd, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Beyond the Body, Bill Mitchell, Daisy Natale, Eyebrow, Hal Smith, John Collingswood, Karol Cysewski, Neil Davies, Noora Kela, Paul Wigens, Pete Judge, TaikaBox, Tanja Råmon, Tilly Webber | Comments Off on TaikaBox: Beyond the Body

TaikaBox: Beyond the Body, Aberystwyth Arts Centre, November 28

photo: Michal Iwanowski

Taika is a Finnish word for magic. So TaikaBox is a magic box, which is the nature of a theatre. In the evening’s program there is a quote from Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: ‘We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience.’ In the context of Taikabox, that could describe an evening at the theatre. There is also a quote from Bruce Lee: ‘The intangible represents the real power of the universe – it is the seed of the tangible.’ If we substitute ‘theatre’ for ‘universe’, we arrive at the same proposition: what we see on stage (the tangible) is our human response to what is invisible (intangible), but we can only express this if we are spiritual beings to begin with.

This brings us to the starting point of choreographer Tania Råmon and designer John Collingswood’s Beyond the Body: the nature of spirituality itself, or what makes a human being. As anyone who reads the company blog will realise, the creative process includes a veritable smorgasbord of inputs, from Kabbalistic mysticism, Qigong, Carnival and running to meditation, states of consciousness and the use of neurological perceptions. We don’t see any of this, of course, but some of it nevertheless finds expression — perhaps a little too literally at times — on stage. As we walk into the auditorium there are five dancers dressed in beautifully designed, loose clothing (by Neil Davies) seated in the lotus position on a white stage. The two musicians are just visible in the wings and there is a perfume of incense in the air. This is no ordinary performance; it is an arresting — and perhaps even uncomfortable — image for those expecting an evening of dance, but it underlines the inside-out nature of Beyond the Body: it is concerned less with formal questions of performance than it is with exploring what produces the formal solutions.

It is when the dancers move that the magic begins, as it is the movement that triggers the painting of light that Collingswood has developed into a visual dance language. A projection of light falls on Daisy Natale as she sits in meditation, then on Karol Cysewski and the other three in turn. The arms of the dancers then set their torsos in motion, and the projection of light expands with them like a painted aura as they rise and move until the light around each dancer merges into that of the others like splashed white paint and the entire stage seems to respond to each and every movement providing a beautifully diffused illumination. Collingswood is clearly in his element here, experimenting with light as an extension of the moving body. During the performance, he uses his imagination and technical wizardry to conjure up energy fields, transform the stage into clouds, trace the flight of a single gull until its path fills the space, and link smoke or ink-inspired patterns and shadows to the movement of the dancers. It is the lighting that closes the gap between technology and dance, but which at times has a tendency, because of its novelty, to attract attention to itself: the images of smoke are beautiful in themselves but tend to overpower the stage action and when a mandala is projected down on to the dancers its spiritual significance is reduced to an illustrative pattern. We are on the borderline of digital art and stage dance; it seems with a little further push in this direction, there will be no dancer but a projected kinesthetic image. Interestingly, one section of Beyond the Body is a choreographic essay of Collingswood’s lighting imagery to live music (by Eyebrow, comprising Paul Wigens on drums, percussion and electronics and Pete Judge on trumpet and electronics).

So what about the dancers? That Råmon has been able to harmonise a diverse group in such a short time is not simply the fortuitous outcome of an audition process. Råmon has built into the creative process a seven-week preparatory period for the dancers prior to the production period in order, as she writes in the program, ‘to improve (the dancers’) physical potential in the creative process and to reduce the risk of injury.’ Apart from working as a choreographer, Råmon is a consultant in dance science and a cranio-sacral therapist, both of which inform this caring and holistic approach to resolving the challenge of bringing freelance dancers together for a short burst of creativity, and it shows. Each dancer brings his or her exceptional qualities to the stage, but the harmony of their interaction in Råmon’s choreography is tangible.

Since Beyond the Body is an investigation into what makes us human, there is not so much a narrative as a series of episodes based on the qualities of each dancer. Karol Cysewski is The Wanderer, Tilly Webber The Seeker, Noora Kela The Shaman, Daisy Natale The Runner, and Hal Smith is The Creator. From the opening, breathing calm, each dances out his or her respective qualities enhanced by Collingswood’s visual design. The dancers are centred, concentrated, focusing on internal process rather than out into the audience. Noora Kela dances a duet with her disembodied shadow projected on to a filmed forest backdrop (by Collingswood and Bill Mitchell) that reminds me of David Hockney’s giant screen experiments; it is as if we are in the forest, and Kela performs on the forest floor stepping carefully through the leaves as the light filters through the branches. During her dance, the other four enter at each of the four corners of the stage, hemming her in: overtones of the Chosen One, but she is left alone in the darkening forest, rolling over to start a second solo that is angular and seems to stretch in all directions. There is a lightness and clarity to her dancing, which is a pleasure to watch.

In the next episode, Natale is followed on stage by a shadow of smoke, or a projected ink pattern that seems tied to her feet. Natale has a lovely fluidity of movement and ecstatic poses. Cysewski follows, projecting less of The Wanderer here and more of an enforcer, prone to sudden spurts of movement — almost violent —that appear to control Natale. Smith embodies the calmness and majesty of the Creator as he sits in meditation alone, eyes closed, with very slow arm gestures. Drops of light fall on him and flow away. He moves through the state of calmness to intense trembling when the drops of light increase exponentially as if energy is emanating from his core being. The quartet arrives like a chorus from which Webber detaches herself, dancing expressively with softness rather than angularity. She melts to the ground in fourth position, then stands, turns and sways, generating ripples of light that become the projected mandala. She walks around the rim of the mandala, then to the centre where she starts an energetic finale to drum accompaniment. Natale joins in with swirling arms, then Cysewski and Kela. Smith walks to the centre with one hand on top of the other as if holding something precious. Once inside the mandala, however, the movement phrases owe more to disco than to the esoteric. Smoke is projected, the mandala turns as the dancers pump up the energy, expanding, jumping and turning in a visually rich painting of light and movement before the dancers finally come to rest as the ripples of light expand in the silence and the dark.

There is clearly more than meets the eye in Beyond the Body; the creators and dancers have entered this inside-out creativity and produced a work that opens up new ground. It is based on the dancers — their spiritual and physical wellbeing — rather than on building up a formal performance. It is thus a work about the process, and if on the way it becomes a tad self-conscious there is also at times a powerful symbiosis between concept, movement and lighting that makes the creative journey rich and fruitful.

Posted: December 8th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Anthony Missen, Company Chameleon, Elena Thomas, Gemma Nixon, Jonathan Goddard, Kevin Edward Turner, Miguel Marin | Comments Off on Company Chameleon: Pictures We Make (preview)

Company Chameleon, Pictures We Make (preview), Z-Arts, Manchester, December 7

photo: Mickael Marso Riviere

Wrong. Company Chameleon’s new show, Pictures We Make, has nothing to do with film or television, as I conjectured at the end of my review of Gameshow. It returns instead to the company’s more familiar roots in contact improvisation and partnering. On Friday evening at Z-Arts in Manchester, Kevin Turner and Anthony Missen took their new work out for a run and they were not alone. For those familiar with Turner and Missen as a duo, this is a new departure for they rarely if ever dance together here; they are too busy discovering the joys of interacting with Gemma Nixon and Elena Thomas who make up the quartet of characters. Pictures We Make explores the question of relationships, of ‘how we navigate the space between our experience and expectations’ as we plunge from I to We. ‘Our insecurities and perceptions about how things should be are tested and reflected back by those with whom we share relationships.’ It is a sometimes explosive but always passionate involvement between the four of them that has all the familiar physicality of Turner and Missen but with an equally powerful female element that gives as much as it gets. Pictures We Make will be one of two works on a double bill that will have its première on February 14 (an appropriate date for a theme of relationships) at The Lowry. The second work, to be created by Jonathan Goddard and Gemma Nixon, will go into rehearsal next week. This evening’s showing was in front of invited guests and friends to garner feedback as much as to put in a good run before the creation of the second work begins.

The ‘pictures’ of the title refer to snapshots of relationships lived and remembered, of emotions exposed and hung out to dry, of joys as well as sorrows. Because there are only four characters and their proclivities are heterosexual, it is all too easy to interpret the heady display of relationships as a lot of feral swapping between the two couples, but there are no bust-ups or recriminations between the two men or the two women, which suggests the memories do not exist on a collective level but within the experience of each individual over a long period of time. Who ends up with whom is immaterial, as the narrative doesn’t run in that kind of linear progression: it is only the framing of the ‘pictures’ that closes the circle and gives the proximity of relationships an almost incestuous flow. What the various duets allow is the exploration of a rich seam of emotional involvement, and each dancer gives of him or herself in a risk-taking, primal way one audience member later characterized as relentless (the pictures we make are not always pretty, and if the pictures in this work were photographs, some of them would have been ripped up or burned). There are solos as well as duets: the solos – I am thinking particularly of Thomas’s – reveal the inner turmoil in the context of the particular relationship. Towards the end, Thomas is like a filly that is learning to get up, angular, awkward, unable to support her weight at first, but determined to place those legs under her. Of all the characters, she shows a certain emotional fragility — a victim almost — though she matches the other three in the abandon with which she approaches her relationships. Nixon sets the emotional tone with her opening solo, and seems to be in her element throughout the work, lyrical and tough with a formidable gaze when roused. The two men, divided in their attentions, nevertheless form a powerful unity.

The only props are chairs, a whole pile of them in the exposed wings and some on stage which become islands occupied by the recovering or simmering characters. Nixon is adept at hurling the chairs across the stage in moments of acute frustration or hurt. The starkness of the metal-framed wooden chairs is in marked contrast to the emotional maelstrom that engulfs the relationships, like the setting of an annual dance between the boys’ school and the girls’ school down the road.

Miguel Marin created the score as so many stories sewn together, finding a sound for each character and adjusting those sounds according to the situation in which they find themselves. It works beautifully with the choreography and its theme.

Looking back, the use of chairs and the circular nature of the relationships suggest a vestige of musical chairs, a game in which only one person is left standing. The transition from ‘I’ to ‘We’ inevitably comes down to ‘I’ after all.

Posted: December 5th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Barbican, Davide Di Pretoro, Jessica Wright, Max Richter, Rain Room, Random Dance, Random International, The Curve, Wayne McGregor | Comments Off on Wayne McGregor | Random Dance: Dancing in the Rain Room

Wayne McGregor | Random Dance in Rain Room, The Curve, Barbican Centre, December 1

There is an installation at The Curve in the heart of the Barbican Centre that allows you to walk through the rain without getting wet – no umbrellas provided. It is Random International’s Rain Room and it is a thing of beauty to behold and to walk through. Walk slowly and the movement sensors in the ceiling will track you and keep the rain from falling on your space; as you walk you mould a dry bubble around you. If you walk too fast you get wet. On some days (all too few: for details you will have to consult the Barbican website) the space is shared by dancers from Wayne McGregor | Random Dance, which adds a whole new, fluid dimension to the installation. Jessica Wright and Davide Di Pretoro were dancing on the day I attended and because dancers and onlookers are subject to the same laws of motion sensors, Wright and Di Pretoro were performing uniquely adagio movement, something one doesn’t often have a chance to savour in a McGregor performance. Wright performs for fifteen minutes: a solo, a duet with Di Pretoro and another solo. The vocabulary is based on articulation of all joints and limbs which, slowed down, has the sense of tentacular motion under water, current-driven, rippling, though there is tension in the extended hands and feet and at the limits of articulation. As the dancers move, they push the boundaries of the rain around them, creating a dry oasis that moves with them. McGregor says he has structured 25 hours of choreography for this event, but as you are limited to five minutes in the room because of space requirements and because the queue extends to five o’clock and beyond, the 25 hours will remain largely unseen. The dance sequences are part choreographed and part improvised, and the nature of the performance, by virtue of the way it is presented, is open-ended.

With one floodlight at the far end of the room, the effect of seeing the dance through the illuminated rain is beautiful. As McGregor says in the video link below, to see the installation is to see the rain as a spatial object and the dancers as artifacts in a performative exhibition. Pina Bausch may have preferred her dancers to get wet and to have the sensation of getting wet, but Random International’s Rain Room offers something between projection and the real thing. A score by Max Richter envelops the piece in a suitably fluid sound, not quite watery but sensuous. Random International (no relation to Random Dance) has not yet got the measure of a dry floor so after fifteen minutes of dancing the shoes get quite wet, but for those walking through in the allotted five minutes there is no need for wellies. Another piece of advice for those who would like to experience the Rain Room: the motion sensors see you better if you wear light-coloured clothing (the dancers are in skin colours) and black may fool the sensors into raining on your absence.

Aware of the time constraints on the viewer for this brief, sensory experience, McGregor calls it a snapshot of dance, and there is certainly plenty of that, almost more snapshot than dance: it is a photographer’s delight. But in that snapshot is an opportunity to see beautiful dancers up close in a weather system that enhances the experience. Keep calm, walk slowly, and wear bright colours. It will brighten up the Rain Room, and (if you can arrive early) your day.

The Rain Room is open until 3 March 2013 and Wayne McGregor | Random Dance will be performing again on Sun 20 January 2013 and Sun 24 February 2013 (11am – 5pm). Entry is free to both the Rain Room and the performances. You can find out more about the Rain Room exhibition on the Barbican Centre website.

To watch a video of the installation, use either of the links below:

YouTube

Vimeo

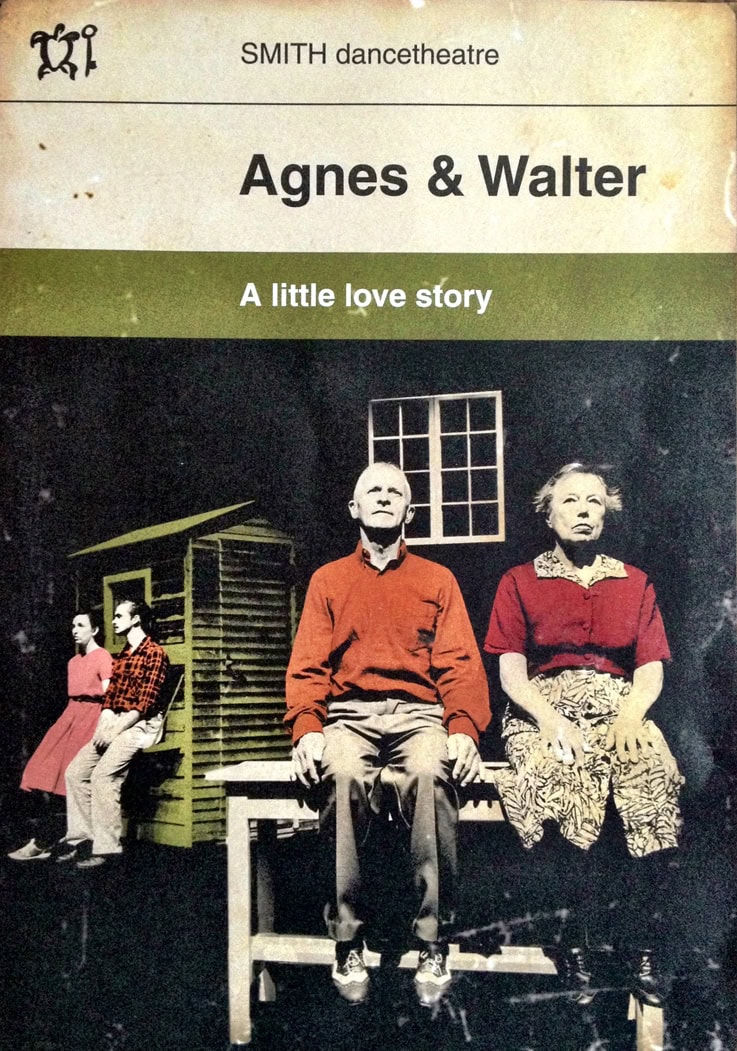

Posted: December 3rd, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aideen Malone, Dan Canham, Elizabeth Taylor, Kate Rigby, Margaret Pikes, Neil Paris, Pavilion Dance, Ronnie Beecham, Sarah Lewis, Smith Dance Theatre | Comments Off on Smith dancetheatre: Agnes & Walter, A Little Love Story

Smith dancetheatre, Agnes and Walter: A Little Love Story, Pavilion Dance, November 8

I had the pleasure of seeing Smith dancetheatre in Neil Paris’ Agnes & Walter: A Little Love Story at Pavilion Dance at the beginning of November. Pavilion Dance has a great venue for smaller-scale dance and a thoughtful, engaging program. The front-end team of Deryck Newland and Ian Abbott nurture their dance and their public in ways that may encourage BBC arts editor, Will Gompertz, to modify his elitist slant on the benefits of arts funding. But back to Agnes & Walter.

I was sure Dan Canham and Sarah Lewis were going to speak in the opening section; language is so close to the surface of their movement that it seemed inevitable it would materialize, but nobody says a word. In that eloquent, perfectly-timed opening sequence Paris introduces the absent-minded, clean cut Walter (Canham) standing at a pale blue table dreamily running a string of Christmas lights through his fingers, checking them without looking. His wife, Agnes (Lewis), in a dress and apron is resignedly sweeping sawdust from the ground around the garden shed (which later doubles as a gingham-curtained house) as if she has done it many, many times before. There is a sense of nostalgia in the costumes (by Kate Rigby) and the set (lit nostalgically by Aideen Malone), a return to what is perceived as a homely set of values and an almost naïve sense of the goodness of life. Walter gets to the end of the string of lights, puts them down and crosses to the shed as Agnes comes over to the table to check the lights for herself (we are not the only ones to think Walter is absent-minded). A few moments later Walter emerges from the shed covered in sawdust, emptying it from his pockets and spreading it at every footstep. Seeing this, Agnes commits hara-kiri in slow motion with a kitchen knife right there on the pale blue table to a melodramatic Hollywood horror score. Walter immediately springs into action as the surgeon in his plastic safety goggles, saving his patient with consummate skill: pulling out the knife, plugging the hole, sedating the patient and stitching her up. He checks her vital signs, has to resort to shock treatment and succeeds in reviving his patient to a sitting position. She falls back but Walter applies his healing hands to her chest; she gestures ‘mouth to mouth’ to the romantic surgeon, so he inflates her by degrees until she reverts to life. She palpitates her heart with a fluttering hand, expresses a certain sadness that the play is over and starts to clean up.

All this makes perfect sense when you know that Agnes & Walter is based on James Thurber’s short story, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. It is an inspired realization, and although it never again approaches its inspiration so purely as in this opening scene, Agnes & Walter confidently develops its own variations with Thurber-like humour. There is the couple of Walter and Agnes in older age, in which it is Agnes (Elizabeth Taylor) to whom her husband’s earlier absentmindedness seems to have migrated. She dances a poignant solo in which she appears to be in a dream, dancing around a maypole, waving at everyone, gathering spirits from the air, pulling them down to her lips as she rises up on tiptoe to meet them. Walter in older age (Ronnie Beecham) is as spry as his wife used to be, maintaining a risk-taking active life, finding pleasure in canoeing on the roof of the shed (as his wife wheels it across the stage) or in performing a rip-roaring dance with a pair of bunny ears around his neck. If this is the golden age, bring it on.

Weaving between the two couples is the figure of their guardian angel or spirit (Margaret Pikes), helping to resolve their problems and lending their narrative an emotional quality that derives from her voice: she does not sing her songs, she lives them, particularly Léo Ferré’s Avec le temps. In fact, music throughout Agnes and Walter – from Tammy Wynette’s Stand By Your Man to Bruce Springsteen to Henryk Gorecki – provides an emotive backbone that reinforces the dance.

Paris’s choreography grows from the ground on which the characters stand, developing from the stillness of a thought into a phrase, just as Walter Mitty’s reveries were sparked from something he saw on his excursion to the shops. With Canham, the thought lingers unhurriedly before the movement develops but Lewis is more spontaneous. Responding to the wind (generated on stage by a 1950s-style standing fan) and to the second movement of Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, she immediately lets down her hair, breathing in deeply, stretching up in ecstasy, her arms dancing up in the air, head raised, smiling, aspiring. She stands on the table to get higher, lets go, and falls to the floor, yet after each collapse, she clambers back to the source of the wind. Feeling the air in her face and hands again, she reaches like a young child pulling spirits from the air (a recurring theme in Agnes & Walter), before the wind finally dies out.

If at first the two Agneses and Walters seem to pass across each other as different couples, towards the end they become superimposed in a quartet of coexisting ages. Canham develops a theme from sweeping the floor into a reverie of uncertain movement; Beecham joins in with his own variation on Canham’s theme. They stumble together, both finishing with arms raised and sitting on the table side by side with their backs to us in touching unity. Pikes, leaning against the shed, sings her final song, Springsteen’s My Father’s House: ‘I awoke and I imagined the hard things that pulled us apart Will never again, sir, tear us from each other’s hearts.’ Taylor and Lewis step pensively on to the stage, step together, step together; Canham and the smiling Beecham gradually join in. Pikes opens the door of the shed and puts up Walter’s Christmas lights in the doorway while Canham and Lewis begin a variation on a theme of making up (this is, after all, a little love story). Lewis lures Canham into the shed, closes the door and turns off all the lights.

There is something about the image of Agnes and Walter in the publicity material that is immediately appealing. In its colouring and content it contains all the elements of the work: its beguiling charm, its emotional range, its generational range, its down-to-earthness and even its literary provenance. It might have its origins in a bygone age, but the reach of the performance draws inspiration from the air and has room to breathe, making the characters in Agnes and Walter never less than fully alive and fully present.

Posted: November 30th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Adam Carree, Andrew Loretto, Anthony Missen, Company Chameleon, dieb 13, Dieter Kovacic, Fabrice Serafino, Gameshow, Kevin Edward Turner, Mat Johns, Signe Beckmann | Comments Off on Company Chameleon: Gameshow

Company Chameleon: Gameshow, Nuffield Theatre, University of Lancashire, November 1

photo: Brian Slater

I saw Company Chameleon at the 2010 BDE in their first work, Rites, which dealt with the relationship of father to son and attitudes toward manhood and growing up. Two years later the duo of Anthony Missen and Kevin Edward Turner is again dealing with social development but from an external perspective. Gameshow is about the insidious values of advertising and mass media — particularly television. In the program note, Missen and Turner write that ‘since the early part of the 20th century, ad men have been selling the public false dreams, lifestyles to aspire to so that we always want the next thing. In creating Gameshow we wanted to parody this, to look below the surface of the commercial world and interrogate the substance of the lifestyles we are being sold. Alongside this runs the deconstruction of the cult of celebrity, a phenomenon driving aspirational lifestyles to a new level.’ Rites was very much a stage work, but Gameshow belongs as much in the television studio: while maintaining their distinctive form of dance theatre, Missen and Turner have collaborated with video artist Mat Johns to produce advertising and hidden camera clips that ratchet up the scope and efficacy of their work considerably. This is the first script Missen and Turner have written, and they have further broadened their collaborative approach by working with dramaturg Andrew Loretto, set designer Signe Beckmann and composer Dieter Kovacic (aka dieb 13) along with old friends Adam Carree (lighting designer/production manager) and Fabrice Serafino (costume designer).

Gameshow’s narrative follows the fate of a game show host, J.O.Z. (Turner in a blonde wig, white jacket and trousers, red shirt and bare feet), whose brash over-confidence diminishes in direct proportion to the increase in tenacity of a wily contestant (Missen). Turner’s opening number is a tongue wagging, hip-undulating, over-the-top dance that exaggerates — but only just — all the piped sex appeal of a game show host looking to assert his personality over the contestant and audience — especially (in this case) the girls. Turner drums up applause as he leaves the stage and basks in the adulation. Once he has left, Missen in tee shirt and jeans rolls on from behind a desk. Not at all used to the spotlight, his movements suggest discomfort, but he has the fire of someone who wants to make his dream come true. His opening dance includes a section in which he seems to cycle on his side across the floor, suggesting a willingness to advance despite the friction.

Gameshow is pure spoof, but embedded in the narrative is a commentary on the role of television advertising in which parody gives way to satire. In the game show’s first commercial break we see (projected on a screen on the back wall) an ad for Solvaproblemol, a dissolvable tablet for relieving symptoms of stress and anxiety. A white-coated doctor (Turner) talks in a snake-oil-salesman’s way about a new product to counter suicidal tendencies. He approaches a figure seated on a bench, pats his shoulder patronizingly and introduces him as a patient who can testify to the product’s efficacy. Instead the patient puts a gun to his throat and as the camera cuts to Turner’s face, we hear the shot, and see Turner’s face spattered in blood. Without missing a beat, the smiling Turner introduces the product that we see behind him in a field, about the size of a giant tractor wheel, as pristine as an Alka Seltzer.

Back in the studio, J.O.Z. is making his contestant jump through hoops (literally) to demean him in front of the audience, and to make himself look good. J.O.Z. exudes contempt by beating Missen with a plastic kosh, and putting a bucket over his head. Just as the treatment begins to remind us of images from Abu Ghraib, the next commercial for a video game corroborates it: two of the contestants resemble Bin Laden and Bush and another two resemble a hoodie and Raptero Cameron. In the video clip the underdog wins. This signals a turning point in the game.

For the next round, Turner asks one of the girls in the audience to pick out a piece of paper from a hat. The rule of this round is that Missen has to rap to whatever subject is on the paper. The girl draws The Lord’s Prayer. Turner is complacent, Missen is in a panic, but he does it and passes to the next round. Through his earpiece, Turner gets a call from his boss who is angry at his mismanagement of the show, and we understand that unless Turner can cause Missen’s downfall, his job and all that it represents is on the line. As the dejected Turner walks out of the studio, we see a slick clip of him as a macho sex symbol whom no beautiful woman can resist. It is in fact an advertisement for a perfume, Messiah, that J.O.Z. is promoting. Turner’s state of mind in the clip is in stark contrast to his state of mind when he arrives home to his wife, who is…Missen in fetching dressing gown and slippers. She goes to comfort her husband but he is in no mood to be comforted; he makes a weak attempt to show some warmth, but can’t bring himself to follow through. The sequence of this domestic dysfunction — made all the more dysfunctional by Missen’s drag — lasts an uncomfortably long time, but the discomfort is a metaphor for the disconnect between the onscreen image and its reality. Jimmy Savile’s story and the BBC’s reaction to his behavior is a recent example.

Turner makes his way back to the studio dreading the final stages of the game. He arrives like a zombie, but when the lights go up his grimace warps back into a smile; the studio is his world. In this final round, Missen has been given the task of making seven people in the street hug him and say they love him. The filming by hidden cameras is beautifully realized, as we see Missen carrying two shopping bags falling repeatedly on a busy pavement at the foot of a succession of unwary individuals in an attempt to gain their sympathy. He does it brilliantly, and once he has gained their attention, he explains his task and asks them for a hug and for each to say I love you. Some don’t want to know, others don’t have a problem. It’s very touching and very funny. Missen gets his seven people and passes this test. Back in the studio, Turner says to his audience ‘Let’s welcome him back’, but doesn’t mean it. He is determined to block Missen’s success and sits him down to a game of three riddles, like Turandot without the opera house: the third riddle is ‘What does God never see, a King sees only once and you see all the time?’ delivered with due condescension. Missen eventually gets it: an equal.

Turner is finished, washed up. He gets home, takes off his wig and jacket, brings out a large fish platter of powder and sniffs a few lines. In his vengeful imagination he engages Missen in a combative dance, which turns to violence, but Missen starts to beat the ever-smiling Turner at his own game, until he leaves him defeated on the floor in a pool of light needing desperately a dose of Solvaproblemol that he had so cavalierly endorsed.

One of the qualities I remember from Rites is the physical prowess of both Missen and Turner, not only in their individual dance sequences but in the closeness with which they worked together. In Gameshow, dance is used to great effect in the expression of the contrasting characters of host and contestant, but the dance sequences are not as central to moving along the story as the text and film. Both Missen and Turner put in excellent performances in their respective film roles.

The soundtrack by Dieter Kovacic is everything one would expect from a composer who has worked continuously since the late 80s ‘rendering cassette players, vinyl, cds and hard disks into instruments’ and it links each segment of the show effectively and sensitively with both a lovely sense of humour and pathos.

Because the setting of Gameshow straddles both theatre and television, getting the right balance of stage environment is a challenge. Television has slick production values, leaving little to the imagination, while the stage is more ‘handmade’ and leaves much to the imagination. The camera can also screen out unwanted elements in the studio, whereas in the theatre what you see is what you get. What you see in Gameshow is a set designed to accommodate both a television studio and the kitchen table in J.O.Z.’s home, which stretches credibility a little too far. But if the production values of television and theatre have not found a way to coexist seamlessly in Gameshow, the title of Company Chameleon’s new work, Pictures We Make – scheduled to open on February 14 at The Lowry – suggests the research continues.