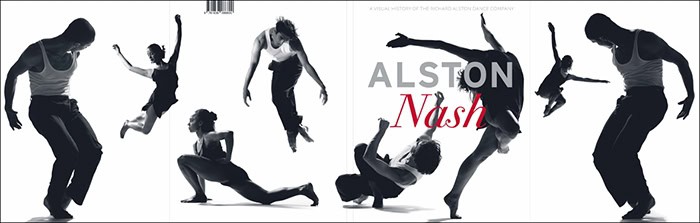

Alston Nash, a visual history of the Richard Alston Dance Company

Posted: October 19th, 2020 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Book | Tags: Allan Parker, Chris Nash, Darshan Singh Bhuller, Elly Braund, Fiat Lux, Henry Oguike, Ihsaan de Banya, Isabel Tamen, Joshua Harriette, Martin Lawrance, Monique Jonas, Oihana Vesga Bujan, Olcay Karahan, Pure Land, Richard Alston, Samantha Smith | Comments Off on Alston Nash, a visual history of the Richard Alston Dance CompanyAlston Nash, A visual history of the Richard Alston Dance Company, Fiat Lux, 2020.

Choreographer Richard Alston has crafted his life’s work in movement, while Chris Nash has crafted his in the still, graphic format of the photograph. Resolving the ever-present contradiction of recording the one with the other has been the litmus test of successful dance photography. In Alston Nash these two great exponents of their respective arts have effectively choreographed their long collaboration in a series of still images that celebrate movement.

The book comprises 50 of Nash’s photoshoot images from the time he and Alston started working together in 1995 until the closure of the company 25 years later. Studio photoshoots are designed to capture images for advertising purposes — for programs, posters and flyers — and as such they are a close collaboration between photographer, choreographer, costume designer and dancer. While the choreographer constantly wants to free the dancer’s movement, the photographer aims to capture it. Nash is clearly the hunter, and the choreography of Alston the prey. Nash lays his trap with the careful integration of studio lights and shutter speed, and it is evident that his eye is attuned to the dancers in front of him; he cherishes the photographic process to substantiate his feeling for dance, working to translate that feeling into precise imagery and framing. It is part instinct and part message. For an art form that is famously ephemeral, Nash can distil a work into a single image that through the analogous nature of the photograph offers the viewer either an entry into the work or a point of recall. As such, these publicity images represent a timeline of RADC’s choreographic output from both Alston and Associate Choreographer Martin Lawrance; to look through them is to re-capture both the performances and the superb dancers — there’s a list of them all in the appendix of the book — whom Alston has nurtured and raised equally to the level of his choreography. There is also a text that accompanies each of the images in the form of a conversation between the three creative voices of Nash, Alston and Lawrance. As well as being a fascinating insight for dance photographers, these dialogues offer an informal, anecdotal history of the company and individual dancers in the context of each photoshoot.

A sense of time pervades these images, time in which not only have Alston’s style and Lawrance’s choreographic invention developed but Nash’s sensibility too. As Judith Mackrell writes in the introductory Overview, Nash had come to RADC from working with post-modern choreographers like Lea Anderson and Michael Clark where he ‘sought to replicate a similar playfulness — his images manipulated post-production to create surrealist collages or visual puns’. The opening promotional photographs in Alston Nash are of Darshan Singh Bhuller, Isabel Tamen, Samantha Smith and Henry Oguike; they are very much Alston in the image of Nash. Over the years, however, Nash transforms his work in the image of Alston. This can be seen in a comparison between a photograph of Olcay Karahan in Red Run in 1998 and a retake from a revival of the same work in 2019 with Elly Braund. Both are atmospheric images of a human coil of energy ready to unwind and break free, but the photographic treatments reveal an aesthetic evolution.

Even if Alston laments in one of his comments that ‘you can’t photograph a musical phrase’, Nash manages to interpolate in his images a layer of meaning between movement, musicality and the notion of writing dance. In the shot of Joshua Harriette stretched in an airborne figure of speech with Monique Jonas as his elegant anchor in Brahms Hungarian (2018) or in the muscular grammar between Ihsaan De Banya and Oihana Vesgo Bujan in Lawrance’s At Home (2015), he captures what Alston acknowledges as a calligraphic quality in his work. It is this kind of subliminal understanding between Nash and Alston that makes their partnership so rewarding.

It is tempting to read into the book a lightening of tone over the last ten years, as Nash’s sensibility follows Alston’s movement towards ineffable clarity and light, culminating in his final work for the company, Shine On: the elements of these photographs are as emotionally refined as the choreographic imagery. As a visual history of the Richard Alston Dance Company, it will be hard to improve on this finely attuned collaboration.

Alston Nash is the second book of Nash’s imprint Fiat Lux. Beautifully designed by Pure Land’s Allan Parker, it is available from Nash’s own shop or on Amazon as of October 19.