Dance Company Lasta, Naraku (Abyss)

Posted: October 8th, 2025 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aoi Okamoto, Mana Tazaki, Miwa Motojima, Motoi Matsuda, Riku Ogawa, Ros Chase, Satoshi Nakagawa, Yoshimitsu Kushida, Yumika Yasuoka | Comments Off on Dance Company Lasta, Naraku (Abyss)Dance Company Lasta, Naraku, The Coronet, September 18, 2025

Naraku, the title of choreographer Yoshimitsu Kushida’s work for Dance Company Lasta, translates in the program as ‘abyss’, but it is also the Japanese word for ‘hell’. If you add to these meanings Kushida’s program note that ‘reality and fantasy are like two mirrors, reflecting each other and easily transcending the boundaries between them’ along with a description in the freesheet of his choreography as ‘erotic, beautiful and grotesque’, the influence of the Marquis de Sade comes to mind. What transpires on The Coronet stage is indeed infused with Sadeian proclivities — especially in Kushida’s treatment of women — but there are elements of the production that risk being lost in translation.

Under plush red lighting, we see the stage transformed into a Victorian study furnished with a bare desk, a glass-fronted cabinet, two chairs and an Eastern carpet — all of which could well have come from the wonderfully eclectic collection of furniture in the theatre itself. Facing us, sitting at the desk, is a man (Kushida) whose stillness is more than inaction; his presence has entered into the realm of codified Japanese Noh theatre where stillness is not simply the absence of movement but a repository of spiritual and emotional influence. He is evidently fixated by what is going on in his head, and what is going on in his head wields control over the elements of the stage. For most of the performance, until there is the beginning of a resolution, this Sadeian figure remains almost perfectly still apart from some small gestures in stark contrast to the contemporary dance movement Kushida employs for his male characters on the stage. From a Western perspective, it is easier to watch movement and engage in its possible narratives than to engage with stillness and its possible significance.

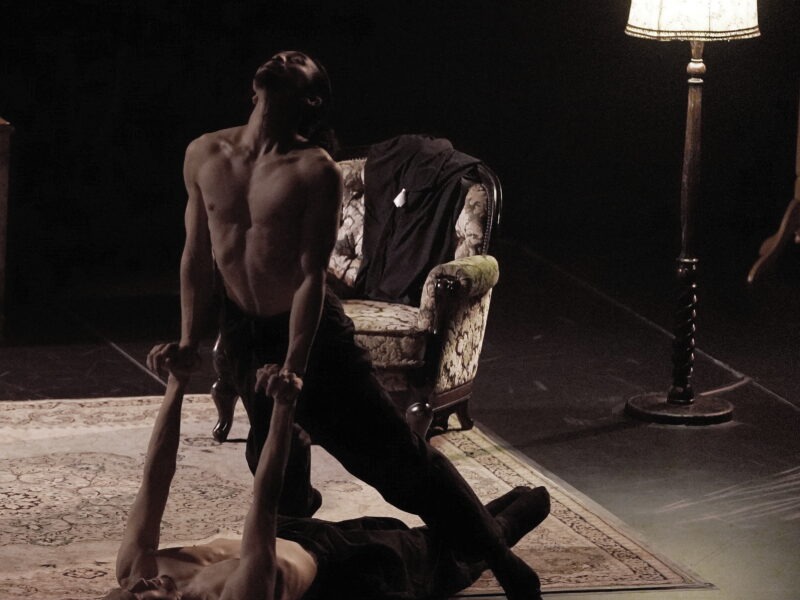

The lighting (by Kushida with Ros Chase) separates episodes of the narrative with blackouts. After the opening image of Kushida at his desk, we see the figure of a half naked Satoshi Nakagawa lying on the front of the stage as if he has been spat out by some giant imagination. He has; it turns out he is the alter ego of Kushida himself, and the other figures — Miwa Motojima, Yumika Yasuoka, Mana Tazaki and Riku Ogawa — are emanations of Kushida’s mental and spiritual turmoil. Only Aoi Okamoto appears to have direct access to Kushida, acting as his conscience, tidying up his books and rousing him to action.

What follows, underpinned by Motoi Matsuda’s dark score, are fantasy episodes involving three women in turn: Motojima, Yasuoka and Tazaki. In a repeated pattern of predatory sexual play between these women and Nakagawa leading to mounting violence and death, Ogawa acts as a moral brake as if Kushida is aware of the excess of his fantasies but is powerless to stop. Ogawa has an exquisite movement quality that is powerful yet deeply spiritual; he curves through space leaving a trail behind him. He is the perfect foil to Nakagawa who cuts through space with a precise muscularity. Their relationship as expressed in their respective physical qualities reflects the fluid boundaries between fantasy and reality and reveals what Roland Barthes would have termed ‘erotic’, the fleeting image that gives pleasure. One might expect that pleasure to extend to the relationship between the men and the three women, but Kushida’s transformation of these women from victims into balletic spirits appears all too familiar to the point of caricature. Motojima and Yasuoka are classically trained, but choreographing this rather fey version of classical dance — especially in their duet — next to the dynamics of Nakagawa and Ogawa jars the imagination and removes the element of fantasy and the erotic where it is conceptually and physically needed. If Kushida’s translation of Noh within a contemporary dance context requires a double take (or a second viewing), his translation of female victims into contemporary wilis is a choreographic form of mixed metaphor. Tazaki’s movement quality is more in tune with the embodiment of a tortured psyche.

Okamoto, whose blood-curdling declamations prove the physical antidote to Kushida’s reverie, eventually brings about a possible resolution. Kushida is stirred into joining the two men, all three stripping down to their waists to grapple with one another. A final image of an exhausted group of men and women around one of the chairs with Kushida in a dominant position appears to banish fantasy in favour of reality. But right after the blackout a spotlight reveals that the figure of Nakagawa has taken his place. It’s a brilliant sleight of hand that returns Naraku to where it started, in the abyss of a Sadeian imagination.